A 5,ooo Year History Of Dalbergia Melanoxylon

A 5,000 Year History Of The International Trade In Dalbergia Melanoxylon

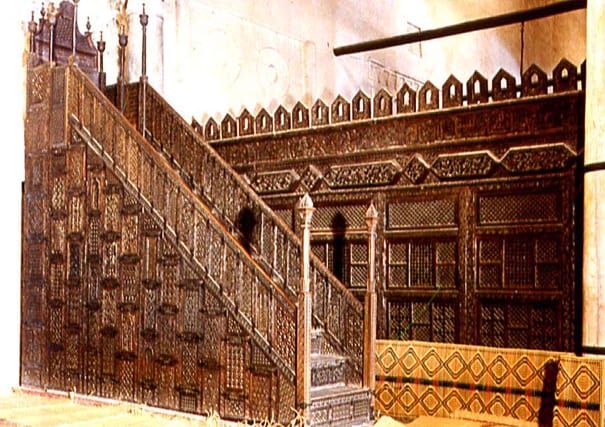

Historical evidence of human use and trade in Dalbergia melanoxylon can be found dating back for over 5,000 years, beginning in the ancient Egyptian culture. It is a felicitous fact for the mpingo researcher that the tombs of the Pharaohs – their contents and construction materials – have been so well preserved, documented and scientifically tested because it has been established that Dalbergia melanoxylon was widely used in the production of the exquisite furniture and artwork possessed by the ruling classes of Egypt. Surprisingly, it was also used in temple construction, as wooden splines holding the immense stones of the pyramids in place, and other construction purposes where a strong wood was needed, such as door latches and hinges. It was widely fashioned into funerary figures and ritual objects. Identical to its use today, it was often used in inlay and marquetry as a high contrast material when combined with ivory, tortoise shell or precious stones. This use of the material has continued through the centuries until the present, proving it to be one of the most important artistic materials the world has ever known.

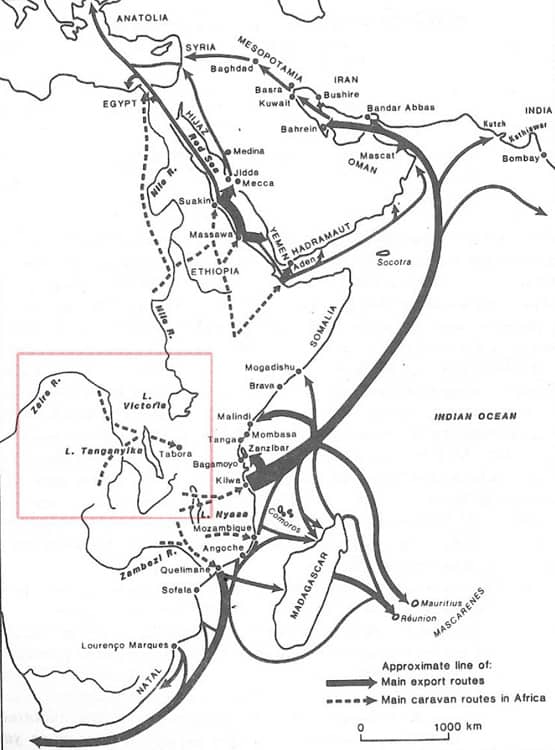

Mention of African blackwood in Egyptian historical writings, inscribed on cuneiform tablets and painted on the walls of their monuments, refer to ‘hbny’, a designation which is the root of the modern word, ebony. Since so many Egyptian artifacts have been recovered and tested, one can be reasonably certain that their descriptive term hbny referred to the species now called Dalbergia melanoxylon. Further evidence for its provenance is the Egyptian documentation of their source of supply, indicating by wall paintings and hieroglyphic writings that it was imported into Egypt from sub-Saharan Africa by two trade passages – along the route of the Nile River, and by way of the Red Sea along the eastern coast of Egypt. The countries of origin were most likely modern Sudan, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Eritrea. These are areas which are now almost devoid of the resource but have climatic and environmental conditions similar to Tanzania and Mozambique, where it is currently harvested.

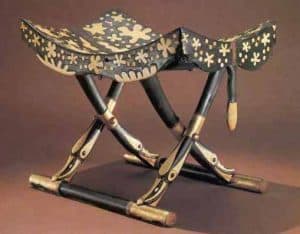

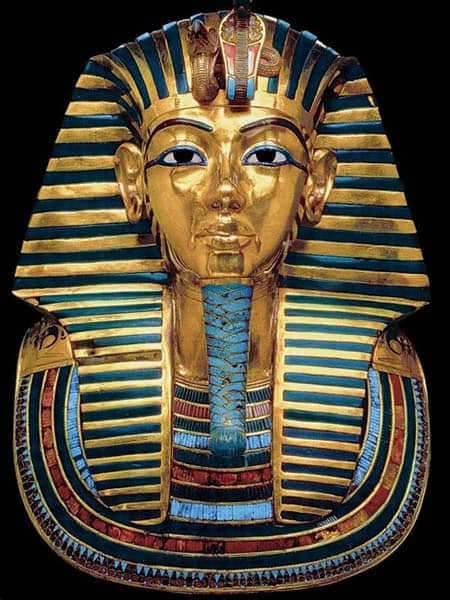

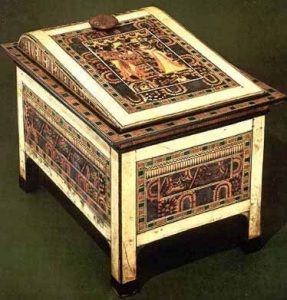

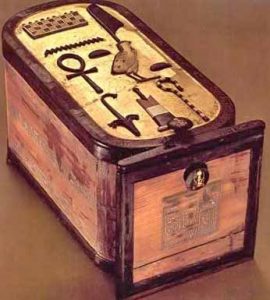

Further verification of Egyptian use of Dalbergia melanoxylon can be found in the book, Pharaoh’s Flowers: The Botanical Treasures of Tutankhamun – 2009, by F. Nigel Hepper, under the entry Dalbergia melanoxylon – Ebony Family – Leguminosae: “It is interesting to note that our English word ‘ebony’ is derived directly from the Ancient Egyptian word ‘hbny’ which refers to a dark, if not black, timber. This hard, expensive wood was used for special furniture such as Tutankhamun’s chair, stool and bed. Pieces were also incorporated in the shrine doors as bolts, and were used for a gaming-board stand, legs of another chair and the framework of boxes. Even part of the doorframe into the burial chamber was of ebony (combined with pine and date palm). Thin sheets were used for inlay and as a veneer of high technical standard. However, the black guardian statues were painted, presumably to look like ebony, as were several other objects in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Botanically the Ancient Egyptian ‘ebony’ is a different timber from the tree in the genus Diospyros now known by that name. The dark wood found in Tutankhamun’s and other tombs came from Dalbergia melanoxylon, a member of the pea family. It occurs in dry wooded grassland south of the Sahara, from where it would have been exported to Egypt. It grows as a spiny shrub or tree 5–30m (15–92ft) high, often with several trunks, none of which is very thick. The heart-wood is purplish brown, verging to black. The leaves are compound with three to four pairs of small leaflets, and its pea flowers are small white and fragrant. Since the timber is immensely hard, one wonders how the Ancient Egyptians managed to work it and, in particular, how they made sheets of veneer from it. As the Egyptians were seeking a jet-black timber, the name ‘ebony’ later became attached to Diospyros species from tropical Africa, which have almost black wood and, even later, to Diospyros ebenum, from India and Sri Lanka, which is now the main timber known by that name.”

Commenting on the thrones, chairs and stools in Tutankhamun’s tomb, he writes, “The great variety of seats was quite remarkable. They ranged from magnificent thrones to lowly stools, each having a timber framework. Nobody has made precise identification of all the species involved except for the well-known ones of cedar (Cedrus libani) and ebony (Dalbergia melanoxylon).”

For this reason, after pharaonic times one can no longer be certain of the exact provenance of woods referred to as ebony without having scientific species identification, so care must be taken in research of written historical sources. Where positive identification can be made, this summary will cover the available evidence to show the historic role that Dalbergia melanoxylon has played in the culture and arts of a succession of civilizations in recorded history.

In the Tombs of the Pharaohs

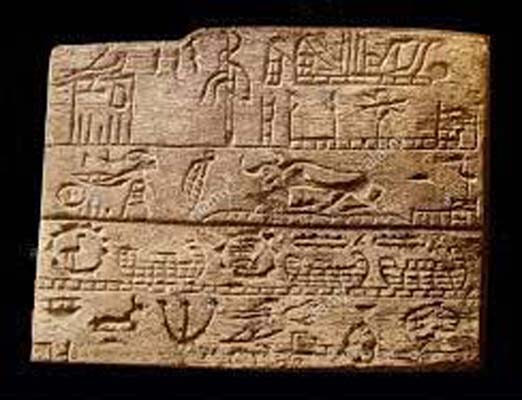

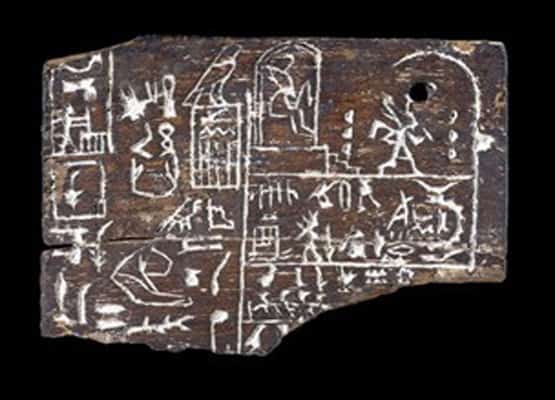

Two of the oldest known extant artifacts of African blackwood are the engraved tablets pictured below. The one on the left is ascribed to King Menes (c 3200-3000 BC), the legendary first pharaoh, and the one on the right to the Emperor Den, whose 42 year reign began in 2970 BC.

Ebony Plaque of Emperor Menes (c. 3200 –3000 BC) – Inscribed blackwood tablet recovered from the tomb of King Menes at Abydos. In Egyptian mythology Menes was said to be the first human ruler of Egypt, directly inheriting the throne from Horus, the deity of kingship and the sky. As the leader who first united upper and lower Egypt he was the founder of the first Egyptian dynasty. This inscription is one of the earliest known examples of hieroglyphic writing.

Ebony Label of Emperor Den (c. 3000 BC) – Engraved wooden label made of African blackwood. Labels like this were customary on trade goods and would often advertise the fame and exploits of a reigning king. On this label in the upper right hand register Den is seen on his throne at the left with the god Horus behind him. On the right he is running a symbolic race, which was a ceremonial event to renew the Pharaoh’s power and strength.

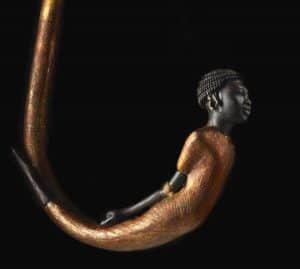

Blackwood was also used in functions which served both a decorative and utilitarian purpose, like the blackwood latches on the gold-gilded wooden shrine of Tutankhamun (left below) and the neck of an ebony harp (right below) estimated to have been created during the New Kingdom period (c. 1550-1069 BC).

Dalbergia Melanoxylon In Temple Construction

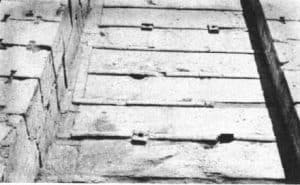

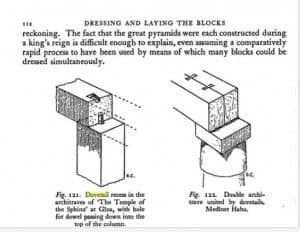

African blackwood tenons were used by builders since the early days of the empire to add stability and strength to temple construction. Some of these tenons have been measured to be five feet long. Beginning in 1924 the Oriental Institute of Chicago conducted a decades-long excavation of the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, recorded in detailed reports. Their excavations revealed the use of Dalbergia melanoxylon in the form of dovetail cramps which were used to align and stabilize some of the timbers and the immense stonework foundations and walls of which the temple was constructed.

Murals And Temple Paintings

Since wood was a scarce commodity in Egypt, most buildings were constructed of limestone, sandstone, granite and handmade mud brick. Wood was considered a high value import and generally reserved for royal use and ornamentation. African blackwood was obviously included in this category because it was often mentioned as an important trade item along with listings of ivory, gold, incense and tortoise shell. This is called a “trade package” because commodities that are found in similar geographic habitats are often accessed together.

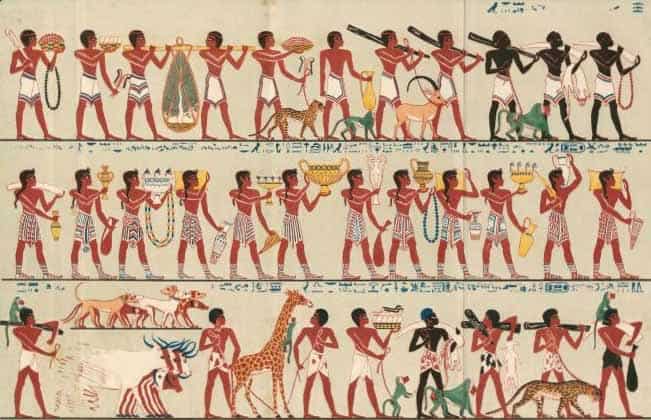

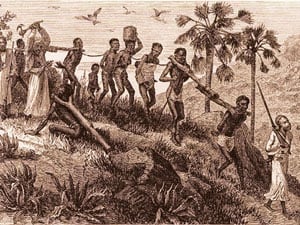

Some of the most revealing evidence of the use of Dalbergia melanoxylon in Egyptian times comes from a number of wall murals that show transport of the wood from central Africa through networks established along the Nile. The people who transported the wood were called Nubians (also referred to as Kushites) and they ruled territories south of present day Aswan. It is probable that the Nubians themselves had extensive trade contacts with merchants in sub-Saharan kingdoms who supplied them with resources that were plentiful in the central forest belt of Africa. The temple murals depict the Nubians bringing ivory tusks, ebony logs, incense, exotic animals and animal skins, gold, slaves and other precious commodities to the downstream Egyptians.

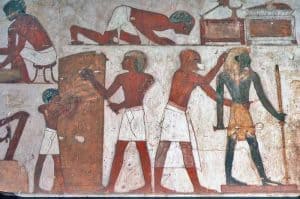

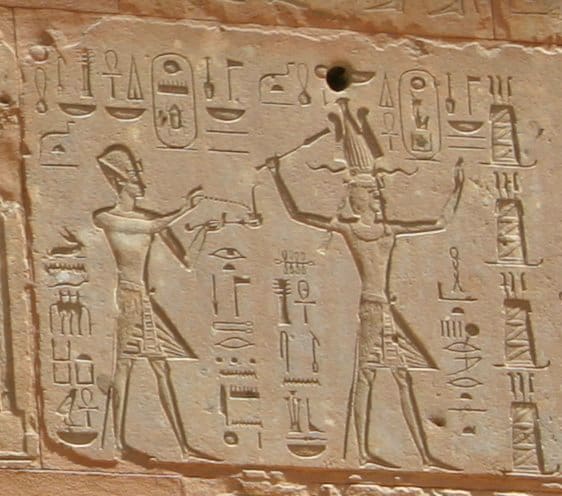

Although they were important trade partners, historically the Egyptians and the Nubians were also adversarial and the border between the two kingdoms shifted over the centuries depending on which kingdom was more successful in expanding militarily. The Egyptians in general considered the Nubians an inferior people, but excavations of Nubian pyramids and cultural sites at Meroe have revealed a civilization rivalling that of the Egyptians. Below is a detail from one of the huge wall friezes in a temple built by Ramesses II (1303-1213 BC) at Beit el Wali near Aswan. It shows in great detail the caravans of porters bringing numerous trade products into Egypt.

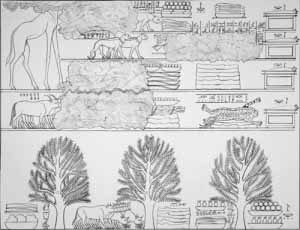

Plaster relief of wall painting from the temple of Beit el-Wali, built by Ramesses II, dated 1279 BC. (Left) Nubian porters transport blackwood logs (top and bottom right), elephant tusks (top right), gold vessels, cattle, exotic animals and a variety of other goods. (Below) Finished blackwood products: blackwood runners, fans with blackwood handles and blackwood chairs adorned with gold leaf.

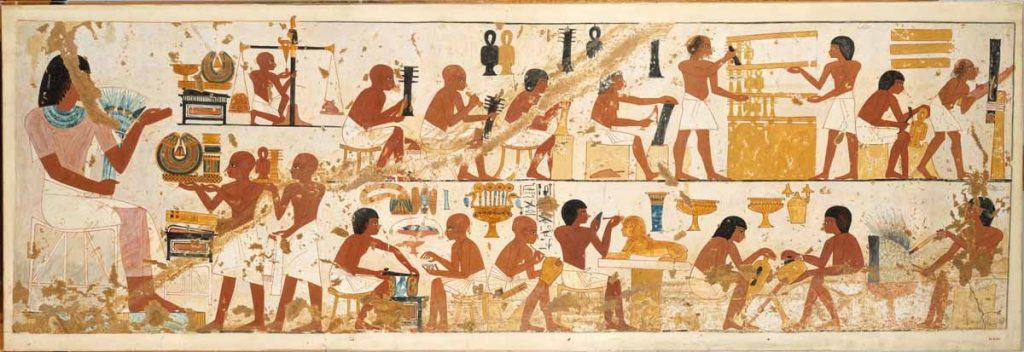

In The Royal Workshops Of Rekhmire

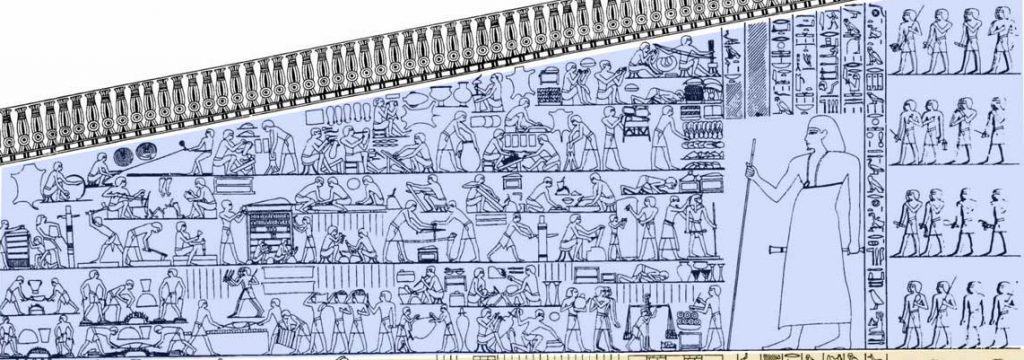

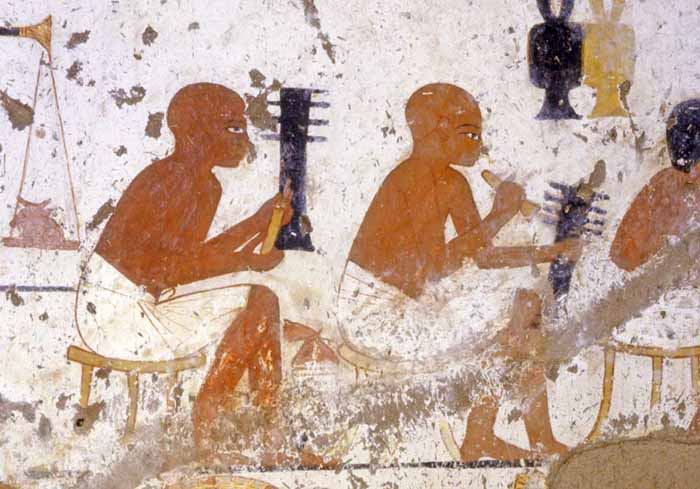

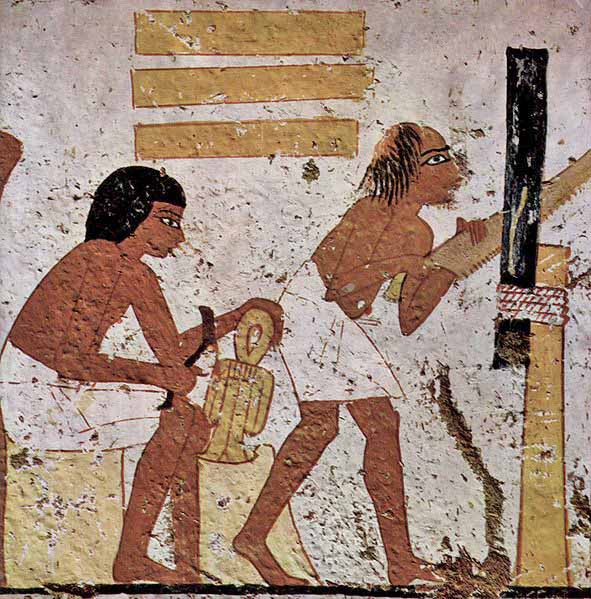

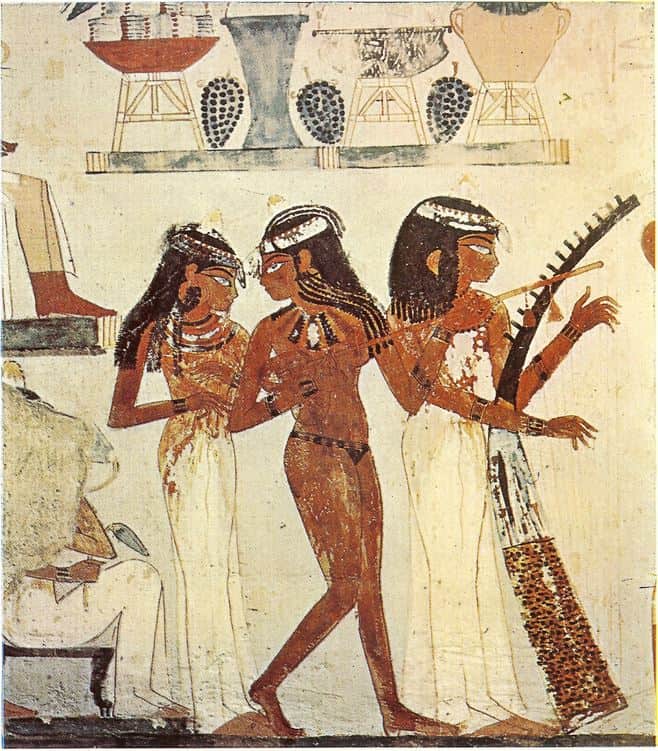

Temple paintings also show the workshops of Egyptian royalty, where craftsmen fashion ‘hbny’ into furniture items and ritual objects. Rekhmire (18th dynasty) served as vizier (high-ranking political advisor or minister to the pharaoh) and steward of the Temple at Karnak during the reigns of Thutmosis III and Amenhotep II, and in this position he managed numerous building projects throughout the kingdom. As a noble he was buried, like royalty, in a splendidly decorated tomb. Friezes on the walls of his tomb reflect the work done under his direction, showing scenes of carpenters, carvers, goldsmiths, jewelers and various craftsmen producing decorative and utilitarian objects for the royal families. Some are depicted milling and carving African blackwood.

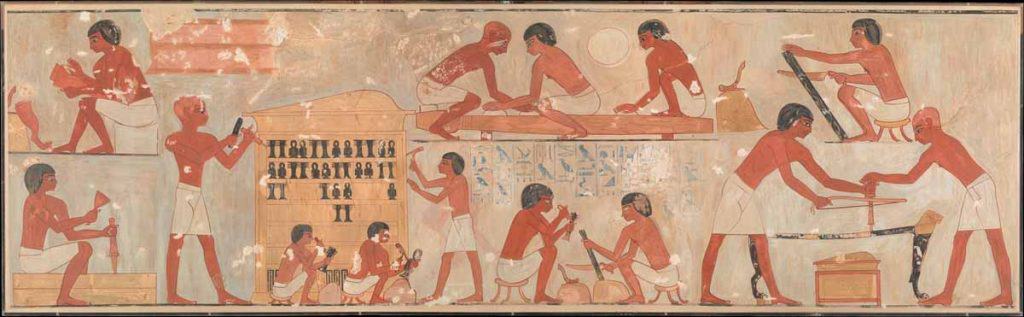

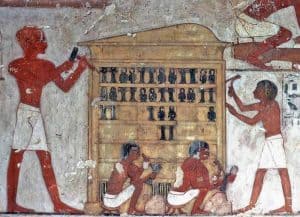

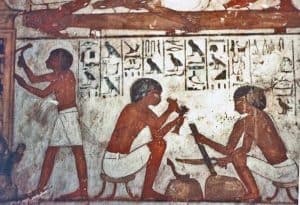

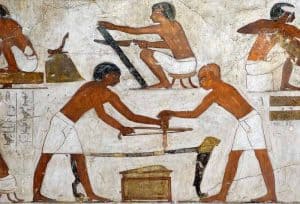

Above is the caricature of a frieze on a wall in Rekhmire’s tomb executed by Nina Davies, showing scenes of his workmen, with a dominating figure of Rekhmire to the side as the grand overseer and his attendants behind him. Scenes of carpenters can be seen on the third course from the top. Above this area is the hieroglyphic inscription: “Making chests of ivory, ebony, carob wood, meru wood, and of cedar of the best of the terraces; by this official who gives the regulation, guiding the hands of his craftsmen.” Below are reproductions of the original wall paintings, showing the carpenters, many of whom are working with African blackwood.

The paintings shows the production of ritual objects known as the Djed Pillar and the Isis Knot, which are commonly found symbols in Egyptian mythology. The Djed Pillar is associated with Osiris, the Egyptian God of the afterlife. With a central shaft and four circular bands at the top, it was said to symbolize the spine. Such an amulet hung around a mummy’s neck was said to ensure that the mummy would regain use of its spinal column and become able to sit up in the afterlife. It was also used as a protective charm by the living.

The Isis Knot, also called the Tyet Amulet, was similarly used in burial rituals in the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1070 BC) and placed on the upper torso for protection in the afterlife. The Egyptian Book of the Dead, an Egyptian funerary text, calls for such an amulet to be placed at the neck of a mummy, saying “The power of Isis will be the protection of body.” Similar tomb paintings of the production of these objects were found in the tomb of Nebamun and Ipuky in the next section.

Nebamun and Ipuky - The Tomb Of Two Sculptors

Nebamun and Ipuky were sculptors and engravers by training who succeeded in reaching high positions of responsibility within Egypt, thus allowing them to excavate and decorate their own (shared) burial complex. Similar to Rekhmire, paintings on the walls of their tomb show craftsmen who were probably working in African blackwood to produce items for the Egyptian royalty. The large personage in the frieze on the left is the overseer, and craftsmen are bringing their finished pieces to him for inspection.

The copy below of the original mural was painted by Nina M. Davies and Norman de Garis Davies who were Egyptologists and copyists hired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to create facsimiles of Egyptian wall paintings. Their works were often published together under the name ‘N. de Garis Davies’.

Queen Hatshepsut and the Land of Punt

The New Kingdom period of Ancient Egypt (c 1570-1070 BC) contained the 18th, 19th and 20th Egyptian Dynasties, with some of Egypt’s most famous rulers at the helm. Hatshepsut was its most powerful queen, her son Thutmose III is known as the “Napoleon of Egypt” and Akhenaten and Nefertiti were the founders of perhaps the first monotheistic religion, revering the Sun God, Aten. A number of the eleven Pharaohs by the name of Ramesses during the 19th Dynasty have become well-known to history and an 18th Dynasty ruler, Tutankhamun, has become the popular face of ancient Egypt because of the more than 5,000 artifacts discovered in his tomb. Such artifacts, along with temple inscriptions and written correspondence have enlightened modern historians about the history, activities and beliefs of these ancient peoples, revealing how, in some ways, they seem so similar to us. In the following section, a bit of this history will be traced, as it concerns royal trade in Dalbergia melanoxylon.

Queen Hatshepsut (c. 1478–1458 BC) was an Egyptian queen known for her prowess in establishing friendly trade relations with nations in sub-Saharan Africa. Her Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahari near Luxor was so elegantly designed and executed that its distinctive architecture presaged that of the Parthenon by a thousand years. Hatshepsut is perhaps best known for her seafaring voyages by way of the Red Sea to the legendary Land of Punt, called by Egyptians the “Land of the Gods” because of the abundance of its natural resources. Scholars today think that the Land of Punt was located in modern Eritrea or Ethiopia.

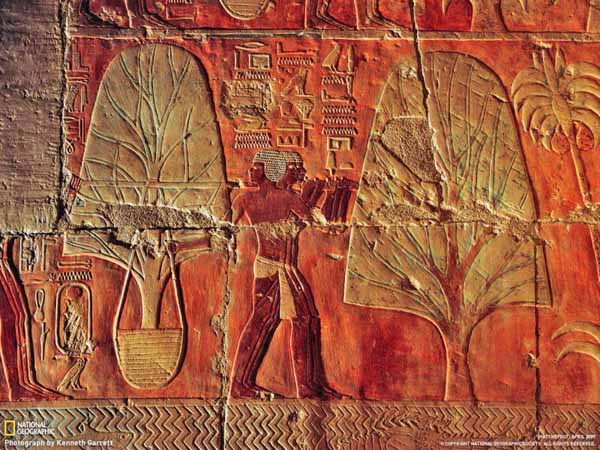

Carved into the walls of her temple are impressive panoramas, detailed depictions of these famous voyages – the construction and outfitting of ships, their journey southward, trade goods loaded onboard and the journey home. The cargo for the return voyage is listed as “. . . all goodly fragrant woods of God’s Land, heaps of myrrh-resin, fresh myrrh trees, ebony, pure ivory, green gold of Emu, cinnamon wood, khesyt wood, ihmut incense, sonter incense, eye cosmetic, apes, monkeys, dogs, skins of southern panther, natives and their children.” As noted before, the trade package of ebony and ivory are listed together.

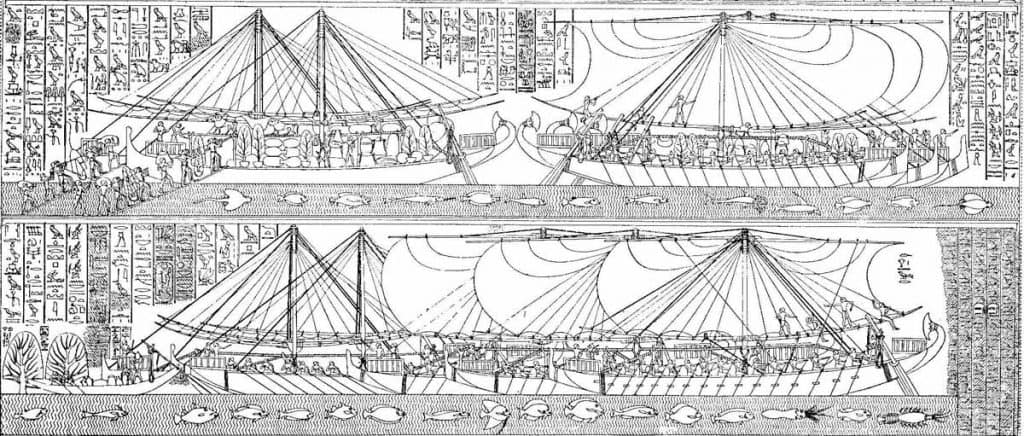

Her best known expedition is depicted below in drawings duplicating the original carved wall murals. A primary objective of this expedition was the procurement of live incense trees, which were later replanted on temple lands in Egypt. Incense was of prime importance for ritual use in temple ceremonies as well as for its preservative properties in the Egyptian’s widespread practice of embalming.

Above is a drawing of Hatshepsut’s five vessels at dock in Punt, with workers loading commodities for the return voyage home. Live incense trees can be seen on the deck. The inscribed hieroglyphic writings to the right and left of the ships describe the events of the expedition. Scientists have analyzed the types of fish shown in the water beneath the ships in an attempt to ascertain more accurately where the ships disembarked and where they sailed.

The location of the Land of Punt has been a long debated issue, but in 2010 researchers using oxygen isotope analysis found scientific indication pointing to a targeted area by analyzing hair samples from several 3,000 year old mummified baboons that had been discovered in royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings where Hatshepsut was buried. In comparing their results with an analysis of hair samples from modern baboons living in several countries along the Red Sea littoral, they determined that the ancient samples best matched those from present day baboons of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

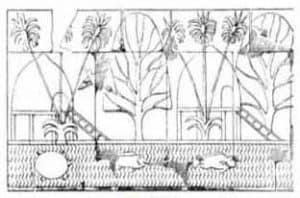

Carved into one part of a frieze, and described in temple inscriptions as “the felling of ebony trees” are drawings executed from the original frieze by Henri Édouard Naville, a Swiss archaeologist who led the team that first excavated Deir el-Bahari in the 1890s. Naville also made drawings of the houses and vegetation of the village of Punt. In one part of the mortuary temple he also uncovered one panel of what he believed was an ‘Ebony Shrine’ that was frequently mentioned in temple inscriptions at Deir el-Bahari.

Hatshepsut’s workers are shown transporting bagged incense trees on poles to load onto ships. At left is a temple carving and at right is a painted mural. Historians surmise that Hatshepsut’s incense tree project was unsuccessful, as they have found little indication of their cultivation in Egypt.

"Ebony Held The Chief Place" - Henri Édouard Naville

In his assessment of the lives of the Egyptians, Naville offers this observation on their use of ebony within Egypt:

“The products of the Land of Punt carried away by the Egyptian ships were many and various. The inscription does not enumerate all those represented; e.g. it says nothing of the cattle and whether they came from Punt or the Land of Ilim. Cattle still constitute the chief wealth of many tribes on the Upper Nile, and travellers maintain that the Soudanese beasts are far superior to the Egyptian, a superiority doubtless already recognized in the reign of Hatshepsut. The text, however, duly records all the precious woods of To-Neter, and among them the Tashep, which M. Loret has identified with the odoriferous cinnamon wood; and the Khesi, which is as yet unidentified but was probably also odoriferous. But of all the woods which formed the staple timber trade, alike of Punt and of Khent Hunnefer on the Upper Nile, ebony held the chief place. In the tomb of Ti we find reference to one of his statues as being of ebony. The wood is mentioned again and again from that time onward to the reign of Ptolemy Philadelphus, who made a troop of Ethiopians bearing two thousand trunks of ebony march in one of his processions. The Egyptians considered the bark good for the eyes, but the wood itself was in chief request for the manufacture of shrines, palettes, furniture and fine cabinetmaking, and works of art in general. Very likely the door and panel which I found in 1893, and which had formed part of a great shrine made for Amon during the joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thothmes II., is of Punt ebony.”

For full text, see: The Temple of Deir El Bahari: Its Plan, Its Founders, and Its First Explorers – Introductory Memoir. Edouard Naville, D. Litt. D. Phil.: Twelfth Memoir of the Egyptian Exploration Fund – 1894.

James Henry Breasted - Ancient Records Of Egypt

James Henry Breasted (1865-1935) was a US-born Egyptologist, archaeologist and historian who in 1919 founded the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago with the financial backing of John D. Rockefeller Jr. Under his leadership the Institute carried out many important archaeological excavations of ancient sites in Egypt, southwest Asia and the near and middle East, and its work continues into current times. Breasted’s primary interest was in Egypt, and he was instrumental in compiling translations of all the then-known hieroglyphic inscriptions. Most of these were tediously copied by hand from Egyptian temples and tombs, often by scribes hanging from precarious ladders and scaffolds in the blazing heat of the Egyptian desert. History owes a debt to those who so devotedly worked because many of the inscriptions are no longer readable due to tomb defacement and the deterioration caused by modern tourism and exposure to pollution. In 1906 Breasted’s compilation was published in five volumes under the name Ancient Records of Egypt. References to ebony, as cited below, are taken from this five-volume compilation. Many of the other quotes referring to ebony during Egyptian times on this webpage were recorded in one of his five volumes.

Weshptah

Weshptah was the chief architect, judge and vizier of King Neferirkare (2483-2465 BC). Engraved on the walls of Weshptah’s tomb is a recounting of the story of how he died. One day when Weshptah is showing the king, his family and his court a new building he had overseen, he is stricken with a debilitating illness. Alarmed, the King quickly summons his priests and chief physician, but to no avail, and his beloved vizier dies. Deep in grief, the King has the body anointed in his presence and orders construction of an ebony coffin. Then he empowers Mernuterseteni, the eldest son of Weshptah to build a tomb for the vizier, which was to be endowed and furnished by the King himself and engraved with stories of Weshptah’s life and works. Concerning his death, it was written, “His majesty commanded that there be made a coffin of ebony wood, sealed. Never was it done to one like him before. . . His majesty had him anointed by the side of his majesty.”

Ebony Shrine of Deir el-Bahari

There are several mentions in Breasted’s work of “The Ebony Shrine of Deir el-Bahari.” When Édouard Naville wrote about his excavation of the site, he recounted that he and his team of archaeologists unearthed the left side door and panel of an ebony shrine. Verification of the building of such a shrine was found in the tombs of three of Hatshepsut’s important advisors, Thuity, Puemre and Habuseneb.

Thuity – Thuity was Hatshepsut’s chief scribe, steward and treasurer, known for his loyalty and devotion. An inscription in his tomb states that he commissioned such a shrine to be built for her, describing it as, “. . . a great shrine of ebony of Nubia; the stairs beneath it, high and wide, of pure alabaster of Hatnub.”

Puemre – Another verification of the building of an ebony shrine was found in the tomb of Puemre, who was a priest and architect serving both Hatshepsut and her stepson Thutmosis III. He left references to his building activities in his tomb and also on his statue, which had this inscription, “I inspected the erection of a great shrine of ebony, wrought with electrum, by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Makere (Hatshepsut), for her mother Mut, mistress of Ishru.” Paintings and reliefs in his tomb also show him receiving tribute of precious materials from various foreign lands. Referring to the tribute from the oasis region of southern Egypt is the inscription: “Inspection of the weighing of great heaps of myrrh. . . ivory, ebony, electrum of Emu, . . . all sweet woods, . . . living captives, which his majesty (Thutmose III) brought from his victories.”

Habuseneb – Habuseneb held an even more exalted role during Hatshepsut’s reign. He was vizier, high priest and architect and thus held political as well as sacerdotal power. During his service to Hatshepsut he united the priesthood of all Egypt into a coherent organization. As architect he had a wide influence over the supervision of construction projects during her reign. Although his name has been largely removed from his tomb, remaining statues of him record his works. One that is now in the Louvre mentions his building of a shrine of “ebony, wrought in gold,” along with “many offering tables of gold, silver, and lapis lazuli, vessels and necklaces.”

Ahmose I

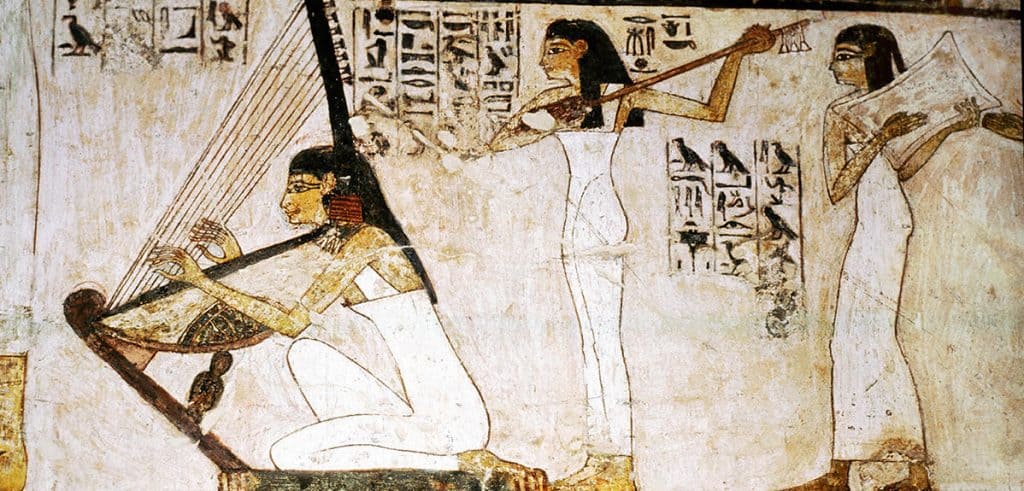

Ahmose I (reign c. 1549-1524 BC), the founder of the 18th Dynasty, reasserted power over parts of Egypt that had fallen into foreign rule. He ushered in a period of great prosperity, reopening trade routes, quarries and mines for the implementation of massive construction projects. Of note in this passage is the mention of the making of “a harp of ebony, of gold and silver.” (See typical harps from this period below.)

“Now, his majesty commanded to make monuments for his father Amon-Re, being: great chaplets of gold with rosettes of genuine lapis lazuli; seals of gold; large vases of gold; jars and vases of silver; tables of gold, offering tables of gold and silver; necklaces of gold and silver combined with lapis lazuli and malachite; a drinking vessel for the ka, of gold, its standard of silver; a drinking vessel for the ka, of silver rimmed with gold, its standard of silver; a flat dish of gold; jars of pink granite, filled with ointment; great pails of silver rimmed with gold, the handles thereon of silver; a harp of ebony, of gold and silver; sphinxes of silver; . . .; a barge of the “Beginning-of-the-River” called “Userhetamon,” of new cedar of the best of the terraces, in order to make the voyage therein.”

Thutmose III - The Warrior King

Thutmose III is regarded as one of the most renowned pharaohs of ancient Egypt because of his military genius and expansion of the Empire. He conducted at least 17 military campaigns in 20 years, resulting in the capture of 350 cities in the Near East, Euphrates and Nubia. He was the stepson and nephew of Hatshepsut and ruled Egypt for almost 54 years, from the age of two until his death at the age of fifty-six. During the first 20 years of his regency, Hatshepsut acted as co-regent, taking on the full authority of kingship. When she died he assumed the throne. Whereas Hatshepsut had expanded her reign by establishing friendly trade relations, Thutmose became widely feared because of his military prowess.

Although Egyptian inscriptions reveal little about the personal lives of the royalty, it is generally thought that there was a great amount of conflict between Hatshepsut (who was his regent) and Thutmose III because she did not allow him to assume his rightful position as pharaoh during her lifetime. One indication of this is that after she died there was an attempt to systematically erase her name from history and deface or destroy the monuments she had built.

A detailed accounting of Thutmose’s campaigns, known as the Annals, is inscribed on the inner altar chamber walls of the Karnak Temple at Luxor, and has given scholars the most complete account of the exploits of any Egyptian king ever recorded. Undertaken between the 22nd and 42nd years of his regency, they clearly emphasize the tremendous quantity of trade goods that were brought into Egypt. The lengthy inscriptions in the Temple probably had the twin objectives of warning potential rivals of his strength, as well as winning the favor of the great Egyptian God Amun to whom the temple is dedicated.

Thutmose III’s most famous battle established dominance over Megiddo (located in modern Israel), and other battles solidified dominance in Minoan Crete, Cyprus, Babylonia and Assyria. Later campaigns sent into Nubia (Sudan) took the Egyptian army further south than it had ever penetrated. The lists of the Annals record huge quantities of timber, metal ores, cattle and grain delivered to Egypt by these subject peoples. Rekhmire, whose temple drawings of artisans and woodworkers are shown above, was vizier during the reign of Thutmose III and many of the materials used by his craftsmen was bounty from these campaigns.

Following are mentions of ebony from Nubia, as recorded in Thutmose’s Annals of the Temple of Amun. The centuries of hostility between the two kingdoms is shown by the Egyptian name for the tribute offered by the Nubians, by referring to it as “the impost of Kush the wretched.” Most of the listings of the Annals for campaigns 7 through 17 include a mention of the bounty of Kush or Wawat.

(Note: In references to gold, 1 deben is equivalent to about 91 grams and 1 kidet is 1/10th of a deben.)

8th campaign: “When his majesty arrived in Egypt, the messengers of the Genebteyew (Nubian tribe) came bearing their tribute, consisting of myrrh, . . . ; 10 male negroes for attendants; 113 oxen . . . and calves; 230 bulls; total, 343; besides vessels laden with ivory, ebony, skins of the panther, products . . .” 9th campaign: “Impost of Kush the wretched: gold, 300 deben; 60 negroes; the son of the chief of Irem . . . , oxen 95; calves 180; total, 275; besides [vessels] laden with ivory, ebony and all products of this country; the harvest of Kush likewise.” 10th campaign: “Impost of the wretched Kush: gold, 70 deben, 1 kidet; slaves, male and female, oxen, calves, [besides vessels laden] with ebony, ivory, all the good products of this country, together with the harvest of [Kush, likewise].” 13th campaign: “Impost of the wretched Kush: gold, 100 deben, 6 kidet; 36 negro slaves, male and female; 111 oxen, and calves; 185 bulls; . . . besides vessels laden with ivory, ebony, all the good products of this country, together with the harvest of this country.” 15th campaign: “[Impost of Wawat]: 35 calves; 54 bulls; total, 89; besides vessels laden with ebony, ivory, and all the good products of this country.” 16th campaign: “[Impost of Wawat]: 35 calves; 54 bulls; total, 89; besides vessels laden . . . with ebony, ivory, and all the good products of this country.” There was also mention of trade goods from Punt: “Marvels brought to his majesty in the land of Punt in this year: dried myrrh, 1,685 heket; gold, 155 deben, 2 kidet; 134 slaves, male and female; 114 oxen and calves; 305 bulls; total, 419 cattle; beside vessels laden with ivory, ebony, (skins) of the panther; every good thing of [this] country.”

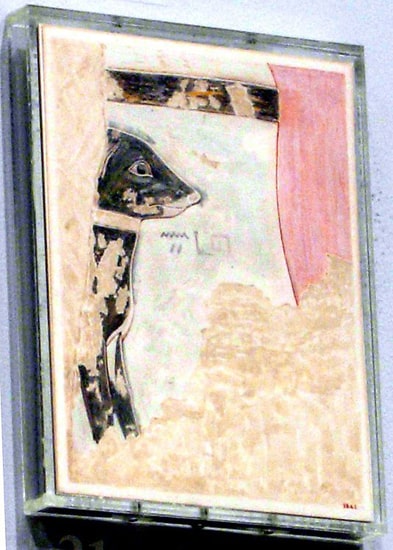

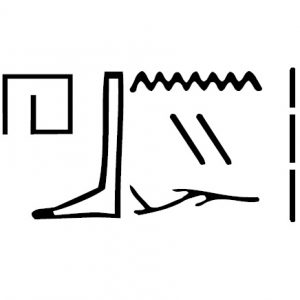

To the left is a painting of the pet puppy of Thutmose III. Of pure black color, it is pictured resting under the pharaoh’s chair, behind his leg and has its name ‘hbny‘, or Ebony, inscribed under its muzzle. Above is the Egyptian hieroglyph for the word ebony. Hieroglyphic writing can be written from left to right, right to left or top to bottom. In the painting the characters are in reverse order from the script displayed above.

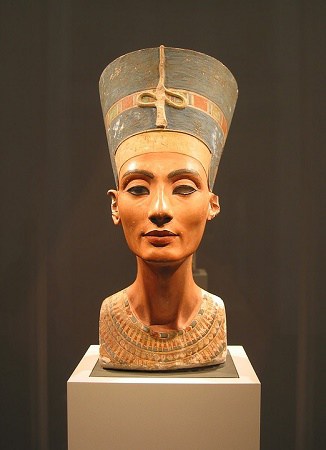

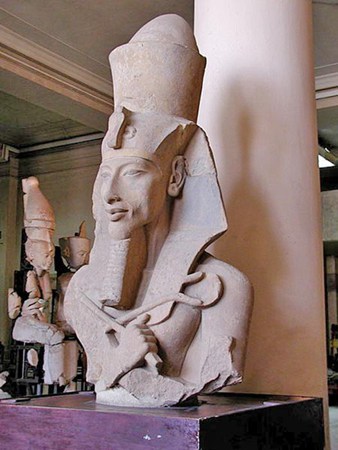

Akhenaten - The Heretic Sun King

Akhenaten (reign c. 1353-1336, birth unknown) was a highly individualistic and iconoclastic pharaoh who separated himself from traditional Egyptian religious belief. He is often referred to as history’s first monotheistic ruler. He was born Amenhotep IV (reign c. 1353-1336 BC), and was the son of Amenhotep III (reign c. 1391-1353 BC), the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty who had brought the country to the height of its political influence and authority. But Amenhotep IV rebelled against his father because he detested the entrenched religious belief system that had been intrinsic to Egyptian life for 200 years. Presided over by a wealthy priesthood, who conducted festivals and ritual offerings in their extravagant temple estates to the deity Amun and over 2,000 lesser deities, he considered the priesthood corrupt and its deities as false gods.

In the fifth year of his reign, Amenhotep IV uprooted the long established Egyptian governing center at Thebes and moved it 200 miles to the north to establish a totally new center of authority at Tell el-Amarna in uninhabited desert on the western side of the Nile Valley. There he built a city of palaces, temples and homes dedicated solely to Aten, the Sun God he had come to revere, whom he thought to be the emanating source of all creation. On temple depictions Aten was not depicted in human form, but as rays of light extending from the central disk of the sun. At Amarna Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhen-aten to honor and reflect this deity and positioned himself as the only intermediary between Aten and the world. In these actions, Akhenaten attempted to overthrow generations of traditions, and make virtually superfluous the well-entrenched and long-honored priesthood.

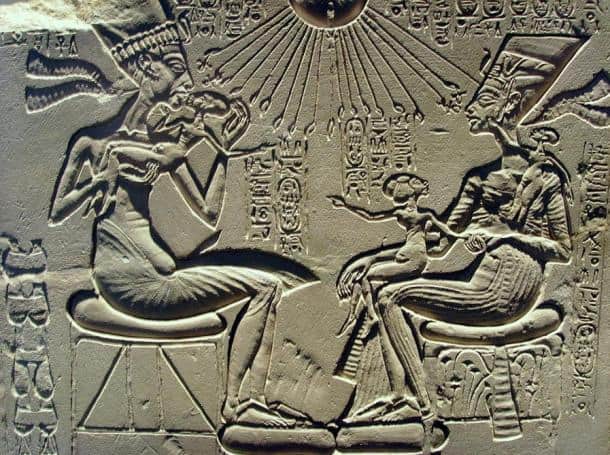

He ruled alongside his wife, Nefertiti, who has become renowned in modern times for her classic image (shown above) as brought to life by the recovery of her statue from an ancient artisan’s workshop in Amarna. It is one of the most reproduced artifacts from ancient Egypt. Reliefs depicting Akhenaten and Nefertiti in Amarna are unique in that they show the daily lives and ordinary activities of the monarchical leaders. Below is an animated and affectionate scene of Akhenaten on left, playing with his child and Nefertiti on the right holding two other children. At center the rays of the Sun God Aten shine upon the family. Tutankhamen was the son of Akhenaten and became pharaoh after his death. Despite Nefertiti being the wife of Akhenaten, it is thought that she was probably not the mother of Tutankhamun. DNA tests have been used to trace many of the Egyptian lineages, but Nefertiti’s mummy has not been found.

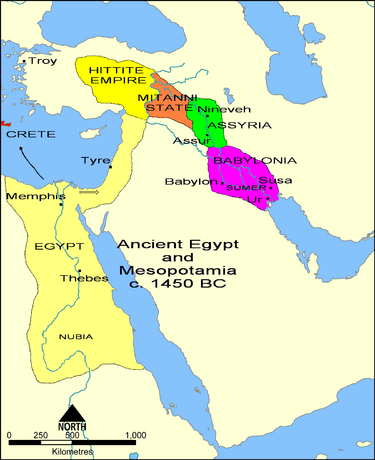

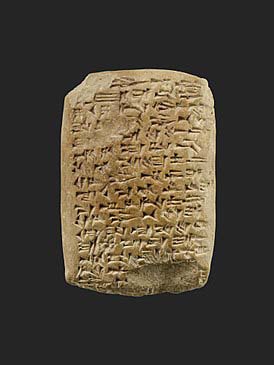

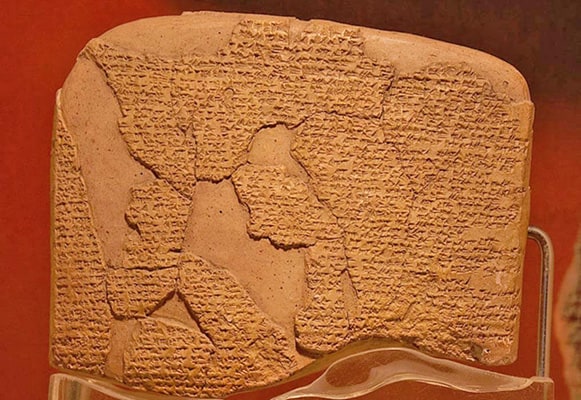

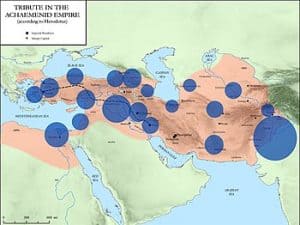

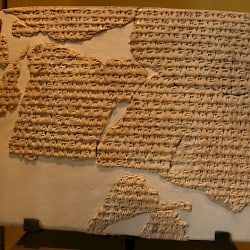

In 1887 a group of local Egyptians, searching among the Amarna ruins for artifacts, found a number of clay tablets with ancient script and quickly sold them on the antiquities market where they found their way to museums in Berlin, London, Cairo, Paris, Moscow and Chicago. Others were found in later archeological digs, altogether resulting in a collection of 350 letters. They were written in Akkadian, the diplomatic language of the time, using cuneiform script, the writing system of Mesopotamia. The archive has given scholars an important glimpse into a period in history for which few written accounts survive, because they are verbatim dialogues in the form of letters exchanged between the rulers of the then leading powers of the eastern Mediterranean – Egypt, Hatti (Hittites), Mitanni, Assyria and Babylon (see map above).

The total correspondence covers a period of only thirty years and is dated to the mid-fourteenth century BC, when Egypt was at the peak of its power and greatest territorial extent. It is evident from the letters that during this period Egypt held great prestige among the five kingdoms, because the other rulers often expressed deference to the pharaoh. Although in the past some of the kingdoms had been at war, during this period there was relative peace between all, and the letters are a remarkable record that sheds light on the culture, trade relations and ways in which the monarchs of the time conducted international affairs and diplomatic relations.

Most of the correspondence is dated to the reigns of Akhenaten and his father Amenhotep III, and many concern details about the royal custom of elite gift exchange between rulers. For the nobility of this era gift exchange was an important ritual between kingdoms, and elaborate treasures were given as tribute to celebrate royal marriages and births, investitures and other occasions of state. Other exchanges were regularly planned, such as yearly tribute paid by vassal states. Generosity and munificence were matters of great importance in gift exchanges between royal courts. A lavish outlay of precious gold or finely produced artistic work contributed much to the prestige of the giver, demonstrating the wealth and prosperity of his kingdom and providing an exposition of all the material resources at his disposal. It was also seen as a measure of his love for his royal brother – the more generous the largesse, the greater the love.

Beyond the diplomatic efficacy of such gifts however, gift exchange was undoubtedly a form of international trade, and because an exalted monarch could not be seen as lowering himself to such a mundane position as that of a common trader, discussion of such exchanges was carefully couched in diplomatic language. The trade caravans that would deliver such items were accompanied by royal emissaries who would act as diplomatic envoys or ambassadors. Detailed documentation was kept, with items carefully described, counted, weighed and recorded at the point of origin to compare with similar records taken at the destination, in order to protect against item substitution and theft.

Of importance for the subject matter of this writing are the numerous mentions of ebony and ivory to be found. This indicates that both were widely traded during the era and that they ranked alongside gold, incense and precious gems as important items of elite exchange between monarchs and the royalty of the era.

Mentions of Ebony in the Amarna Letters

Akhenaten – In a single consignment of gifts sent by Akhenaten to the Babylonian King Burnaburiash II (c. 1360–1333) is noted a total weight of gold amounting to 1,200 minas (600 kilograms) along with a large array of items wrought in silver, notably an exquisite silver monkey with a baby in her lap, along with utilitarian items such as washing bowls, measuring flasks, pails, sieves, devices used for curling the hair, mirrors and cosmetics vessels. Other items were wrought in bronze and stone. Ebony and ivory pieces included delicately carved combs, oil containers decorated with apples, pomegranates and dates along with a carving shaped like an oxen. Add to this an abundance of linen cloth and garments of the finest quality and the total consignment consisted of over 1,000 individual pieces. The itemization of the gifts takes up more than three hundred lines of writing on the tablet.

Amenhotep III – To help furnish the new palace of the Babylonian king, Kadašman-Enlil I (c. 1374 BC – 1360 BC), Amenhotep III sent him a bed of ebony overlaid with gold and ivory and ten ebony chairs overlaid with gold.

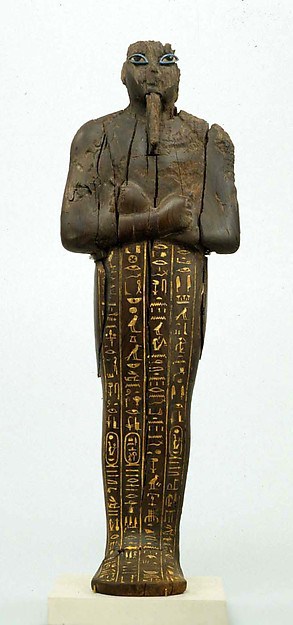

Amenhotep III – In Armana Letters EA 5 and EA 31 Amenhotep III claims to have sent to the king of Babylon four ebony beds, an ebony headrest, ten ebony footstools and six ebony chairs. To the king of Arzawa in Anatolia (modern Turkey) he sent thirteen ebony chairs and 100 pieces of ebony. Apparently the king was fond of ebony for himself, as several of his shabtis (funerary pieces) were made of this exotic wood, as shown below.

This shabti, or funerary figure, was buried in the tomb of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III. It is made of African blackwood, with inlaid eyes of blue, white and black glass. Credit: metmuseum.org

Tushratta – From time to time coalition between these kingdoms was sought through marriage alliances. In 1352 the Mitanni king, Tushratta married his daughter Tadukhepa to Amenhotep III to cement relations between the kingdoms. The listing of the wedding presents (which served as a dowry) accompanying the princess include numerous high value items: a pair of horses, a saddle adorned in gold eagles, a gold plated chariot inlaid with precious stones, clothing of dyed wool and linen, ceremonial weapons and armor, along with objects made of iron (not in common use at the time). Smaller objects included various containers, ornaments and figurines of gold, silver, bronze, alabaster and ivory. Some of the objects were decorated with lapis lazuli, a rare and prized gemstone. Of note is the inclusion of several chests of ebony wood, perhaps to hold some of items sent.

Uluburun Shipwreck

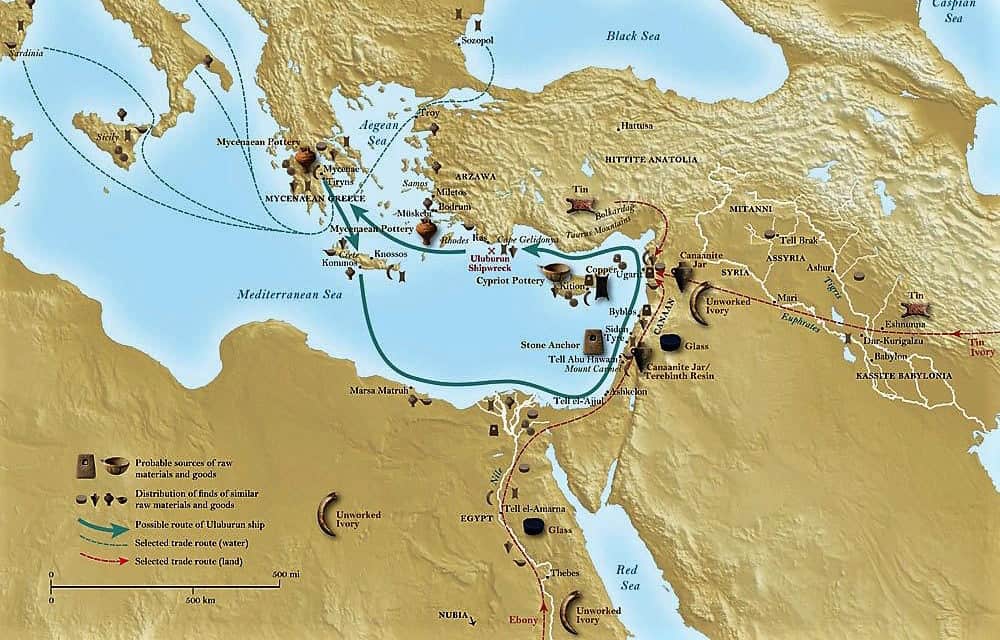

Map above shows an established sea route (c. 1300 BC) in the eastern Mediterranean that took advantage of seasonal currents and trade winds to facilitate a circular counterclockwise itinerary originating in Greece or Crete, with ports in northern Africa, the Levant and Turkey. The Uluburun shipwreck (indicated on the map), as discussed in this section, was carrying trade items from all of these areas probably to a destination in Greece or Crete. Source points for trade goods found on the ship are noted on the map, such as Ebony and Unworked Ivory in Egypt. Credit: Dr. Cemal Pulak – Texas A&M University

Further important evidence of elite trade in Dalbergia melanoxylon was found in 1982 when a sponge diver discovered a sunken ship off a promontory called Uluburun near the city of Kas on the southern coast of Turkey. The ship and recovered contents would come to be described as, “. . . the single most significant key to understanding Bronze Age seafaring.” Various approximations have estimated dates for the shipwreck to have been between 1376 and 1317 BC, exactly contemporaneous with the dating of the Amarna Letters (1360-1332 BC). It is the oldest shipwreck ever discovered and yielded nearly 17 tons of valuable artifacts, the cargo indicating that that it was a shipment destined for a royal court or highly ranked official.

The ten year excavation of the site, consisting of eleven four-month tours and a total of 22,413 dives, was undertaken by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) and led by its co-founder George Bass and Dr. Cemal Pulak, professor in the Nautical Archaeology Program at Texas A&M University. Describing the historical importance of the discovery, Dr. Pulak writes that,” . . . the wreck is considered the world’s oldest seagoing ship and has pushed back the timeline of shipbuilding technology. Examination of the hull and cargo of the Uluburun ship has challenged many previously held assumptions about Late Bronze Age society . . .”

Analysis of the 15,000 recovered artifacts indicates an ongoing trade between possibly 12 cultures – Canaanite, Mycenaean, Cypriot, Egyptian, Nubian, Baltic, northern Balkan, Old Babylonian, Kassite, Assyrian, Central Asian, and south Italian or Sicilian. The planks and keel of the ship were built of Lebanese cedar with a mortise and tenon method of joinery. This is the earliest record of this type of ship construction, and indicates the sophistication of the carpentry of the time. It is thought to have been built on the Levantine coast and its ill-fated last journey to have originated in the vicinity of Haifa Bay on the Carmel Coast of Israel. The loss of the ship and its merchandise must have been a shocking loss for the country of its destination.

Its artifacts have been methodically analyzed as to possible origin and intended destination. The primary cargo was approximately ten tons of copper ingots (354 total) and one ton of tin ingots, widely sought at the time for the manufacture of bronze and in the correct ten-to-one proportion for its fabrication. It is calculated that this amount of bronze would have produced a total of 300 bronze helmets, 300 bronze corselets, 3000 spearheads, and 3000 bronze swords.

Other high-value goods recovered were 149 Canaanite jars and a large number of other containers, Cypriot pottery and oil lamps, a ton of terebinth resin (for the production of bronze), 175 Egyptian glass ingots, thousands of beads of various materials, elephant and hippopotamus ivory, ostrich eggshells, vessels and ritual objects of gold, ivory, bronze and silver, Canaanite and Egyptian jewelry and Mycenaean, Canaanite and Italian weapons. One of the most historically prized items was a scarab bearing the cartouche of Queen Nefertiti, now a rare find because of the destruction of signs of her and Akhenaten’s reign after they died.

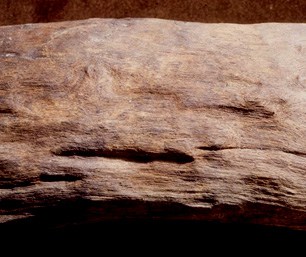

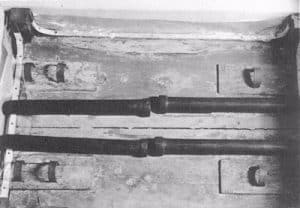

Remarkably, among the discoveries were the remains of about two dozen logs tested to be Dalbergia melanoxylon, an unexpected and rare find given the length of time since the ship had been submerged. Wooden artifacts in salt water are subject to attack by shipworms which bore holes through wood, destroying ship hulls, docks and piers as well as cargo items. Although the logs are quite worn down, fragmented and wormhole-ridden, enough material remained to be able to ascertain that they had been un-milled logs. Their presence within the cargo suggests that they were bound for a palace or other centralized entity capable of mobilizing the resources necessary to operate a workshop skilled in the final production of luxury items.

The two largest pieces of Dalbergia melanoxylon recovered from the Uluburun shipwreck. The sizes of the two pieces shown are 98.8 cm (top) and 106.6 cm (bottom). On right is close-up of weathered surface texture. Credit: Dr. Cemal Pulak

Dr. Pulak kindly provided two photographs of the recovered blackwood, shown above. He wrote: “Since most of the Uluburun ebony logs were heavily damaged by shipworm, there is no way we can estimate how many pieces were originally carried on the ship. Only two of the pieces are well-preserved, and I have copied a photo of them here; all of the other pieces are worm-ridden, smaller fragments. During the excavation we recovered some thirty pieces, of which 18 were entered into our excavation notebooks as “logs” or “log fragments”, and the rest were identified only as “fragments” or “pieces of ebony”. It is not possible to know how many of the fragmentary pieces we found represent individual pieces of logs or multiple fragments from the same log(s). Unfortunately, the Uluburun blackwood logs are not on display; most pieces, in fact, are still in wet storage.”

Given the relative rarity of recovery of Dalbergia melanoxylon objects from ancient and medieval archeological sites due to the fragility of wooden artifacts, finds like those at Uluburun are a vital link in tracing trade in the resource and its royal use during the centuries of its history. Such discoveries bring to life and give credence in modern times to the extant historical records.

In the summer of 2019 excavation began on a newly discovered shipwreck off the southern coast of Turkey that was also carrying copper ingots. It is believed to be of an even earlier date than the Uluburun. This will the third Bronze Age vessel excavated by the INA team at Texas A&M. The first at Cape Gelidonya, Turkey was dated to 1200 BC and excavated in 1960. George Bass, who is now considered the “father of nautical archaeology” led the expedition and is known for the methodologies he developed to make such deep water excavation possible.

• For a detailed description of the excavation and analysis of the finds written by Dr. Pulak, see “The Uluburun Shipwreck and Late Bronze Age Trade”

• View “Ships That Changed History” – In depth YouTube video lecture by Dr. Pulak about the Uluburun shipwreck:

Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibyYNdmdkpc&t

Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xz1eiAY18EY&t

King Tutankhamun - Living Image of Amun

King Tutankhamun (c. 1341-1323 BC) who ruled Egypt for the last nine years of his brief life, has become the modern symbol for Egyptian dynastic rule along the Nile. Yet historically Tut was a very minor figure, deformed from birth, fathering two stillborn infants and himself dying at the age of 19. Why then, has he become the face of pharaonic Egypt?

Most Egyptian temples and tombs have been victim to continuous looting through the centuries, thus divesting them of countless priceless treasures. However, when the entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb, obscured for centuries under a pile of rubble, was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922, it showed little sign of prior entry and opened into an underground chamber that contained over 5,000 artifacts. Because of its pristine condition, it is considered one of the most important archaeological finds in history. The sheer wealth of exquisite artifacts given to the world through the discovery of his tomb has given Tutankhamen a unique and vital place in history as the purveyor of a window into the past.

It is important for our story as well, because numerous exquisite furniture pieces, game boards, art objects, shabti funerary pieces and walking canes fashioned from Dalbergia melanoxylon were still intact. Great pains have been taken with the identification, documentation and restoration of these objects to preserve them for future generations. The King’s sarcophagus and mummy were also intact, and extensive DNA analysis has been done on his remains in an attempt to find answers for his familial associations and the causes of his physical maladies and early death. The treasures of Tutankhamun’s tomb have toured the world in several international exhibits. With completion of the Grand Egyptian Museum near the Pyramids of Giza outside of Cairo, all 5,400 artifacts recovered from the tomb will be on permanent display.

After Howard Carter had excavated the first hole through the wall of the tomb’s antechamber and peered in by the light of a candle, he was asked, “Can you see anything?” The only statement he could manage, as he looked at the gold and ebony treasures inside, were the now famous words, “Yes, wonderful things!” These “wonderful things” are probably the most famous group of artifacts in the world. They attest to the power of human creativity and imagination and highlight the vital importance played by earth’s natural resources in tendering priceless creative treasures for the adornment of its cultures. Below are photos of Dalbergia melanoxylon artifacts from the tomb of King Tutankhamun. The gold gilded shrine and chairs reproduced above are also from the tomb.

1259 BC Peace Treaty Between Ramesses II And Hattusili III

In 1258 BC one of the earliest treaties known to history was concluded between Ramesses II of Egypt and Hittite king, Hattusili III. Known as the Eternal Treaty or the Silver Treaty, it is the only ancient Near East treaty for which both sides’ versions have survived. It records a gift exchange between the two rulers on conclusion of the treaty, stating that Ramesses received horses from Hattusili’s court, a golden goblet encrusted with precious stones, another decorated in gold relief, a gold statue of Hattusili, along with an ebony bed inlaid with gold. Although the treaty itself did not bring peace, and an atmosphere of enmity between the two persisted for many years, a second treaty of alliance eventually did stabilize relations between the nations. A copy of the treaty is prominently displayed at the UN headquarters in New York.

The Fall of Egypt

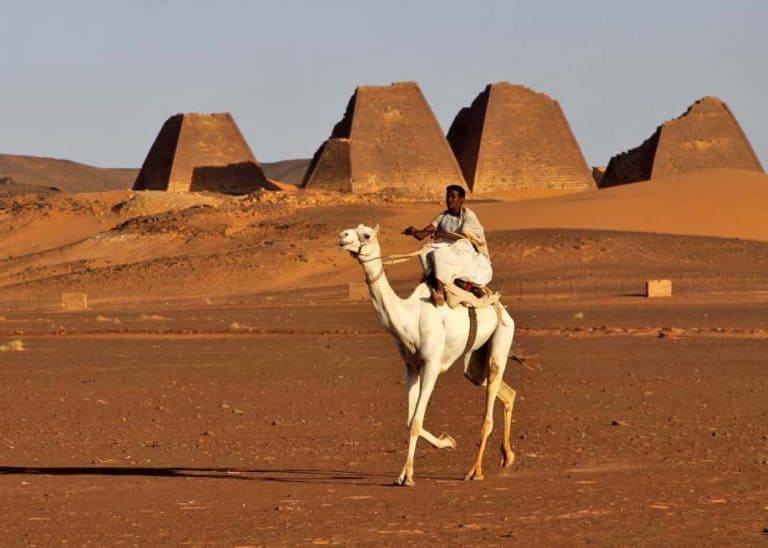

Above left: Painted wooden statues of Nubian soldiers found in Egyptian tomb, c. 2000 BC. Right: Nubian pyramids are proportionally steeper than those of Lower Egypt, such as the pyramid of Giza. There were an estimated 350 in Meroe, although many were submerged after the building of the Aswan Dam. In 1834 Italian treasure hunter Giuseppe Ferlini traveled to Sudan and received permission to “excavate” at Meroe. Having heard local legends of gold buried in the Meroe pyramids, he used explosives and other methods to destroy the capstones, as can be seen on the image. Having found gold jewelry in the first that he vandalized, he went on to similarly deface 40 others, finding only limited additional treasure.

The eighteenth through the twentieth dynasties of Egypt were to mark the high point of that civilization’s astounding achievements and the period was followed by a succession of dynasties marked by slowly declining wealth, influence and ability to retain power. The international prestige that had marked Egypt’s place in history was coming to an end as a series of foreign invaders undermined the ancient kingdom until a stable government was again instituted under Roman rule.

Although the Nubians (also called Kushites) to the south had for millennia been Egypt’s trading partners and lifeline to the commodities of sub-Saharan Africa, they had long been resentful of their subjugation and envious of the wealth of Egypt. Through centuries of interaction, the Egyptian dynasties had often attempted to conquer their territory, but the Kushites, who themselves had a pattern of settlement in the Nile Valley possibly even more ancient than the Egyptians, were known as fearless warriors, renowned for their strength and athleticism and were able defenders of their ancestral homelands. They were among the tallest peoples of the ancient world and many were even recruited into the Egyptian army as specialist archers because their height enabled them to use palm-wood bows which were up to six feet long. Their ferocity on the battlefield was punctuated by their attire of leopard and lion skin and use of red and white war paint. Herodotus described them as “painted half with gypsum and half with vermilion.”

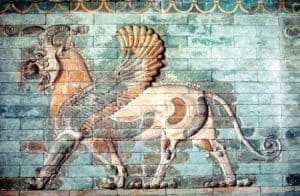

By the 8th century BC Egypt had become so weakened that in 728 BC the Kushite King Piye conquered its territories, united Nubia with Egypt and expanded the kingdom to its greatest historical extent. The Kushites greatly intensified pyramid building in their own homelands and today over 350 pyramids have been discovered in what is present Sudan. The Kushites, however, were only able to hold the kingdom for about 100 years, and in 671 BC they were conquered by the Assyrians. In 525 BC Assyria in turn fell to the army of the Persian king Cambyses II. The Persians established an intermittent rule until 332 BC, at which point the conquests of Alexander the Great brought Egypt under Mycenaean control as the Ptolemaic Kingdom. The native Egyptians had found Persian control so abhorrent that they willingly succumbed to Ptolemaic command. This in turn came to an end in 30 BC when the overthrow of the Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra brought Egypt under Roman rule, a highly prosperous era that lasted until 641 AD.

Throughout these tumultuous times, Egyptian trade networks remained intact, with access to gold, ivory, ebony and numerous other commodities uninterrupted. The following sections will note references to African blackwood, elephant ivory and other high value commodities in texts from these periods.

Persia in Egypt

In 525 BC the Persians (Achaemenid Empire) under King Cambyses II invaded Egypt and instituted a period of rule that was marked by civil strife and numerous revolts, brought on by the cruelty of Persian overlords and high taxes exacted on the native population. In trade documents from the time one sees a continuation of the commodity combination of gold, ebony and ivory, but in this era these resources extracted from northeast Africa were probably sent to foreign lands in increasing amounts.

In a passage from his Histories, Herodotus reports that the Persians continued with the trade instituted by the Egyptian Pharaohs before them, demanding tribute from the Nubians to the south. He writes: “. . . the (native) Persians live free from all taxes. As for those on whom no tribute was laid, but who rendered gifts instead, they were, firstly, the Ethiopians nearest to Egypt, whom Cambyses conquered in his march towards the long-lived Ethiopians; and also those who dwell about the holy Nysa (probably Mt. Barkal, north of Khartoum on the Nile) where Dionysus is the god of their festivals. These Ethiopians and their neighbors use the same seed as the Indian Callantiae, and they live underground. These together brought every other year and still bring a gift of two choenixes (about two quarts) of unrefined gold, two hundred blocks of ebony, five Ethiopian boys, and twenty great elephants’ tusks.” (Herodotus – 97.3)

Herodotus writes further of Ethiopia: “Where south inclines westwards, the part of the world stretching farthest towards the sunset is Ethiopia; this produces gold in abundance, and huge elephants, and all sorts of wild trees, and ebony, and the tallest and handsomest and longest-lived people.” As noted above the Nubians had long been known for their tall and elegant physiques.

Palace Of Darius I In Susa

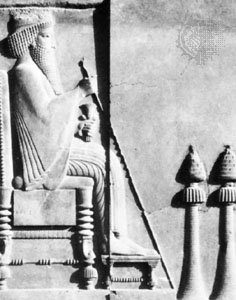

Darius I (550-486 BC), known as Darius the Great, was one of Persia’s most ambitious kings. During his reign, he excelled at organization and architecture, establishing governmental structure throughout Persian lands and instituting numerous building projects, including the construction of a palace complex at Susa, today’s city of Shush, Iran. On a cuneiform tablet found at the site, written in three languages, old Persian, Babylonian and Elamite, Darius tells how he built the royal palace of Susa, using products and employing the skills of numerous craftsmen from all areas of his empire. In the text is a mention of the acquisition of silver and ebony from Egypt, ivory from Kush (Nubia) and the employment of Egyptian craftsmen as goldsmiths and woodworkers.

“This palace which I built at Susa, from afar its ornamentation was brought. Downward the earth was dug, until I reached rock in the earth. When the excavation had been made, then rubble was packed down, some 40 cubits in depth, another part 20 cubits in depth. On that rubble the palace was constructed. And that the earth was dug downward, and that the rubble was packed down, and that the sun-dried brick was molded, the Babylonian people performed these tasks.

“The cedar timber, this was brought from a mountain named Lebanon. The Assyrian people brought it to Babylon; from Babylon the Carians and the Yauna (Greeks) brought it to Susa. The yakâ-timber was brought from Gandara and from Carmania. The gold was brought from Lydia and from Bactria, which here was wrought. The precious stone lapis lazuli and carnelian which was wrought here, this was brought from Sogdia. The precious stone turquoise, this was brought from Chorasmia, which was wrought here.

“The silver and the ebony were brought from Egypt. The ornamentation with which the wall was adorned, that from Yaunâ was brought. The ivory which was wrought here, was brought from Kush and from India and from Arachosia. The stone columns which were here wrought, a village named Abirâdu, in Elam – from there were brought. The stone-cutters who wrought the stone, those were Yaunâ and Lydians. The goldsmiths who wrought the gold, those were Medes and Egyptians. The men who wrought the wood, those were Lydians and Egyptians. The men who wrought the baked brick, those were Babylonians. The men who adorned the wall, those were Medes and Egyptians.”

The Ptolemies

In 332 BC the Macedonian king Alexander the Great wrested the Egyptian lands, along with much of Asia, from Persian control, and established the city of Alexandria at the mouth of the Nile as the center of Greek culture. In 305 BC, after the death of Alexander, one of his generals, Ptolemy I Soter, laid claim to the portion of Alexander’s conquest that included Egypt, declared himself Pharaoh, and established the Ptolemaic dynasty.

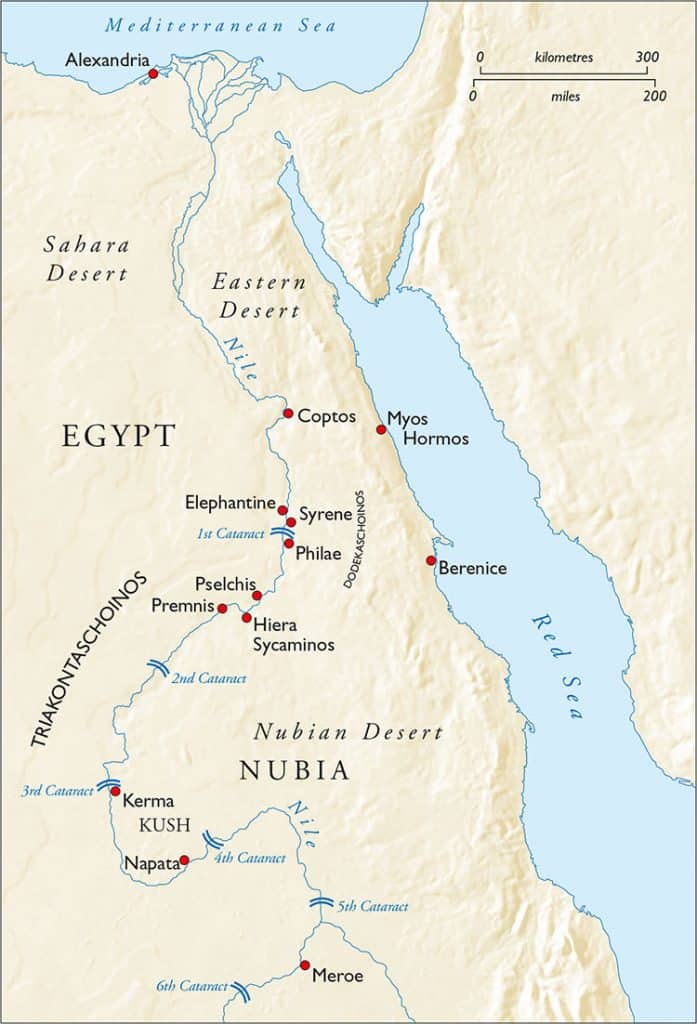

Whereas the Persians had been little involved in its internal affairs, the Ptolemy’s adopted the accoutrements of Egyptian cultural and political life. Having richly profited from their widespread conquests, they set out on one of the richest building projects in history, constructing temples, baths, gymnasiums, research institutes and libraries. To resource materials for these ventures they extended their import trade into new regions. They became much more aggressive seafarers than their predecessors and expanded trade routes along the Red Sea, accessing regions further south along the shore of eastern Africa than had been possible for the Egyptians. Along these shores they solidified alliances with local inhabitants who would access the needed commodities inland and deliver them to the newly established Red Sea ports.

War Elephants

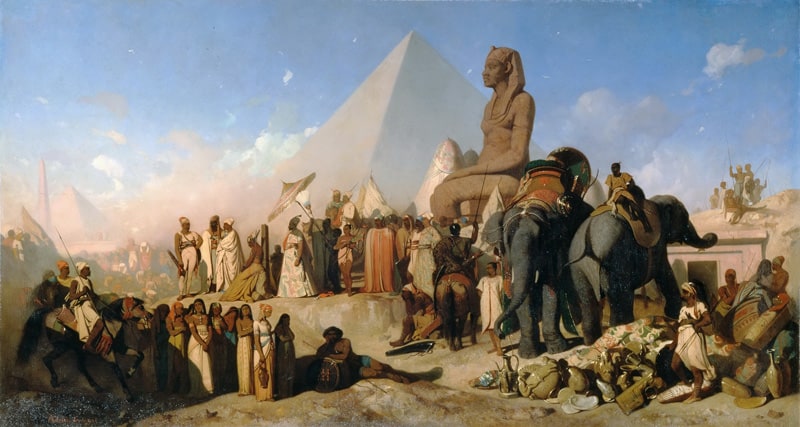

Ptolemy II Philadelphus set up an ambitious project to import live elephants for their use in war by way of the Red Sea, using localized traders to track down elephant herds. To this end he established ports at Ptolemaïs of the Hunts (50 miles south of modern Port Sudan), Berenice, Arsinoe (near modern Port Suez) and Myos Hormos (modern Quseir al-Qadim). Elephants were a difficult and dangerous cargo and giant ships called elephantegoi were built for the trade. When returning vessels docked at Berenice, the elephants were gathered into herding pens, then marched overland to the Nile River (a 2 week journey), then taken aboard barges and shipped to stables and training areas in northern Egypt.

When the hunting fields of Ethiopia became exhausted, Ptolemy’s merchants would make arrangement with new bands of hunters, moving south along the coast to open up new supply routes. By the end of the Ptolemaic era, trade networks for elephants had been established as far south as northern Somalia. It was reported that the elephant populations in the hinterlands of the Red Sea were exhausted by the Ptolemies in less than a century and their use in war came to an end. The African forest elephant had proven to be far less capable than the Indian elephant which was larger and easier to train due to its long history of human interaction. Nevertheless the elephant hunts persisted and the far more lucrative trade in ivory continued to decimate ever wider habitats of elephant populations in eastern Africa, as it has done through the centuries and continues into modern times.

War elephants, as shown above, were used not only in antiquity but even into modern times because of their strength in transporting supplies and the terror they instilled in battle. The Seleucid elephant at right is almost totally clad in armor.

The Grand Procession Of Ptolemy Philadelphus

The ports of trade established during Ptolemy II’s reign brought into the dynastic coffers huge revenues, and the luxurious consumption and profligacy of his court were unparalleled in the world of his time. Callixeinus of Rhodes has provided modern scholars with a lens into these extravagances by his description of a “Grand Procession” staged by Ptolemy in 278 BC in honor of Dionysius. Described as one of the most ostentatious spectacles the world has ever seen, through 32 pages of minute detail Callixeinus describes the successive displays advertising the wealth and luxurious lifestyle of the empire, parading massive numbers of gold and silver objects, ebony logs, statuary and vessels, exotic animals, elaborately costumed and ornamented actors, mimes, priests, priestesses, servants and slaves.

One passage showing the somewhat outrageous extravagance of the procession notes, “Next came a four-wheeled cart thirty-seven and a half feet long, twenty-one feet wide, and drawn by six hundred men; in it was a wine skin holding thirty thousand gallons, stitched together from leopard pelts; this also trickled over the whole line of march as the wine was slowly let out. Following the skin came a hundred and twenty crowned Satyrs and Sileni, some carrying wine-pitchers, others shallow cups, still others large deep cups – everything of gold. Immediately next to them passed a silver mixing-bowl holding six thousand gallons, in a cart drawn by six hundred men.” The objective of such an elaborate spectacle was not only as a show of wealth, but it was also a way to establish legitimate Ptolemaic control over Egyptian subjects. As a grand finale the great procession ended in a military parade, with an infantry numbering 57,600 and cavalry containing 23,200 soldiers.

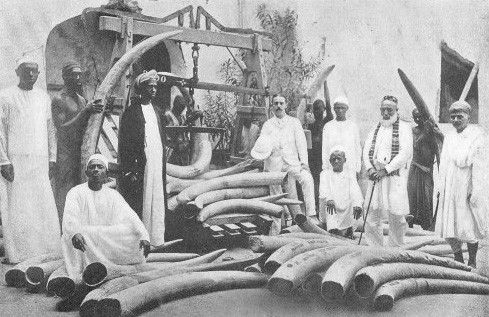

The following passage contains mention of elephant tusks and ebony logs, “Then came camels, some of which carried three hundred pounds of frankincense, three hundred of myrrh, and two hundred of saffron, cassia (medicinal plant), cinnamon, orris (root used for perfume), and all other spices. Next to these were negro tribute-bearers, some of whom brought six hundred tusks, others two thousand ebony logs, others sixty mixing-bowls full of gold and silver coins and gold dust. After these, in the procession, marched two hunters carrying gilded hunting-spears. Dogs were also led along, numbering two thousand four hundred, some Indian, the others Hyrcanian or Molossian or of other breeds. Next came one hundred and fifty men carrying trees on which were suspended all sorts of animals and birds. Then were brought, in cages, parrots, peacocks, guinea-fowls, and birds from the Phasis and others from Aethiopia, in great quantities.” Such descriptions bear witness to the fact of the huge reliance of the human race on environmental resources from its earliest beginnings. The fact that such reliance has resulted in over consumption and species depletion and extinction is not a modern phenomenon, but one that has deep roots in the historical record.

The Roman Empire

Map above shows important Red Sea ports and Nile Valley trade routes used by the Ptolemies and later Romans. Myos Hormos and Berenice were built by Ptolemy II Philadelphus to access elephants and trade commodities. The Romans used the same Red Sea ports and also established a marketplace at Hiera Sycaminos on the Nile River for trade with the Nubian Kingdom to the south of Egypt.

In 30 BC Roman legions defeated Cleopatra VII, the last Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt, in the Battle of Actium, and for the next 700 years Egypt was ruled by Rome, issuing in a new era that if anything was even more opulent than that of the Ptolemies. Rome quickly took full advantage of its newly gained access to Red Sea ports in eastern Egypt and developed a rapidly expanding trade with east Africa, India and the Far East. Whereas the Egyptian and Ptolemaic rulers had only sent out a few vessels a year, the Romans were soon scheduling 120 yearly voyages from Red Sea ports. Trade in commodities was to become the primary focus and means of funding the Roman state. Transporting trade goods by sea was 30-60 times cheaper than using overland routes and often safer and faster. In this way the Romans were able to access at ever greater distances from Rome the incense, spices, ivory, tortoise shell, and precious woods on which they came to rely.

Because of their far-flung empire they had access to several woods with color and texture similar to blackwood, all of which came to be described as ebony. Mentions of ebony in their writings could have referred to a number of woods, one of which is resourced from western Africa – modern Gabon ebony (Diospyros crassiflora), and several from southeast Asia and India – East Indian ebony (Diospyros ebenum), Macassar ebony (Diospyros celebica), and Malaysian blackwood (Diospyros ebonasea).

A robust trade to access Dalbergia melanoxylon in eastern Africa continued to be maintained however, given the fact that Egypt was their primary trading partner, supplying not only gold, ivory, ebony and precious gemstones, but agricultural produce that provided the people of the metropolis of Rome with their free yearly allotment of grain sponsored by national funds. Unfortunately since so much of the Roman Empire was pillaged during its demise and its climate is unfavorable for wood preservation, little woodwork remains that could be tested as to exact wood type. But it is certain that African blackwood was a high-value commodity for the Romans and that many of the references to ebony in their writings would refer to African blackwood.

Hiera Sycaminos

In 22 BC, not long after the Roman conquest of Egypt, the Emperor Augustus sent his prefect Petronius into Kushite (i.e., Nubian) territory, sacking its capital of Napata and overturning the ruling Queen mother Amanirenas. Ensuing battles led to the eventual signing of the Treaty of Samos in 20 BC. The treaty established a boundary line with a buffer zone between Roman and Nubian territory at Hiera Sycaminos (modern Maharraqa) 75 miles south of Aswan, and ushered in a 300-year period of peace.

With the establishment of friendly relations between the two nations, a thriving commodities market was set up at Hiera Sycaminos, where the Nubians and the Romans could freely exchange goods. It was described by the Greek philosopher Philostratus: “This is a market place where the Aethiopians (Nubians) bring all the products of their own country; and the Egyptians (Roman vassals) take these goods away, leaving in place their own wares considered to be of equal value.” The trade was conducted in an unusual way. Traders from Meroe (i.e., Nubia) would first set out their goods and then withdraw from the meeting place to allow the Roman merchants an opportunity to examine the products. The Romans in turn laid out a number of exchange items in front of the goods they wished to acquire in the hope that their offers would be acceptable. If the Nubian trader was satisfied, then he took the Roman wares and left his African goods in the possession of the Roman merchant. All of this business was conducted on trust and although the exchanges were supervised, there were no guards present to watch over these valuable goods.

Philostratus describes how the pagan philosopher Apollonius visited the trade market at Sycaminos just before the exchanges were due to take place. He saw gold, a quantity of linen and a live elephant tethered ready to receive trade offers. Other commodities offered for exchange included “various roots, myrrh and spices with all these items lying around at the meeting place without anyone to guard them.” Pliny also described the market, noting a range of valuable gems supplied by Meroitic traders including black obsidian, red garnets, a golden-yellow stone called hammonis (possibly ammonite), highly-reflective heliotropes and the best magnets “which in our markets are worth their weight in silver.” Due to their alliance with the Kingdom of Kush and their expanding trade routes along the east Africa littoral, it is probable that the trade in Dalbergia melanoxylon greatly increased during the Roman era. Demographically, the Roman Empire had a much larger population to supply with trade goods. At its height, its population was about 65 million people, while that of Egypt was less than a tenth of that, estimated at 5 million. Since its wealth depended on the commerce of trade, commodities procured from its client kingdoms were shipped to numerous nations in its ever-enlarging trade network.

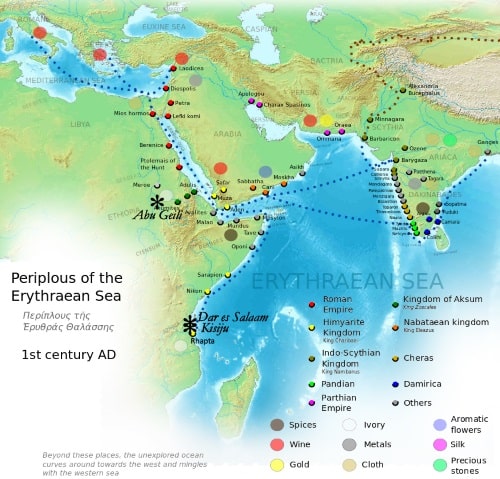

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

The ancient Greeks regarded the Erythraean Sea as the combined Red Sea, Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf. Almost the only surviving Roman era account describing trade voyages in these waters is a document entitled The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Written by an unknown Greek mariner probably around 50 AD, it is unique in subject matter, because it is the only book of the period which spells out an exhaustive survey of the international trade between Rome, Africa, Parthia, India and China. It describes trade routes, trade winds, ports of entry, goods exchanged and a range of information of use to the seafaring merchant about the cultures encountered and maritime difficulties to be expected in different localities.

For the Romans, a primary objective of conquest and contact centered on opening up trade routes with vassal states, and east Africa was important to them for ivory, tortoise shell, gold, silver and ebony. One Roman report claimed that Africa had ‘flourishing forests filled with ebony trees’ and ‘ and ‘a mountain called Chariot of the Gods which rises to great height and glows with eternal fires’. This was probably the volcano Erta Ale in northeastern Ethiopia. The ports and interior trade networks of eastern Africa through which the Romans were likely to have obtained blackwood were located in present day Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania. Many of these had never before been reached by a Mediterranean civilization and were prime growing regions for the species. As Rome used its considerable technological brilliance to master the art of seafaring, it was able to open trade with ever more distance ports of call, eventually reaching India, the Persian Gulf and mainland China.

Above map illustrates ports of trade for Roman vessels, as described in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Of note, black asterisks and white circles denote locations of elephant capture at Abu Geili (Sudan) and Rhapta (Tanzania). Rhapta was described as a place “in which there is ivory in great quantity.” Both locations are ideal habitats for Dalbergia melanoxylon.

The Romans greatly expanded the trade in elephants begun by the Egyptians and Ptolemaic rulers, using them for war, coliseum shows and ivory. Their predation is thought to have caused the extermination of the North Africa Bush Elephant, which was extinct by 300 AD, and they had to increasingly rely on trade with sub-Saharan Africa. The most important use was for their ivory, a product which took on a widespread appeal for the nobility of the empire. Patricians commissioned furniture made of solid ivory to display at well-attended dinner parties as a sign of wealth and prestige, and it was even used to decorate the interiors of temples and other buildings. Tortoiseshell was also prized, competing with ivory in its use as veneer. The Horrea Galbae were enormous warehouses in Rome located near ports on the Tiber River that contained 140 rooms for storing grain and commodities for the Roman population. A contemporary archaeological excavation of the site uncovered a storage chamber that contained 675 cubic feet of ivory splinters from tusks. Although these were only offcuts, their combined mass was equivalent to the weight of 2,500 tusks. Trade in ivory was an enormous source of revenue for the Roman state.

Elephants were not the only African animal used by the Romans. Leopards, lions, ostriches, panthers, tigers, large snakes, hyenas and monkeys all found their way into the empire, with uses ranging from slaughter in the Coliseum to the manufacture of their skins into clothing and decorative items. In 301 AD Diocletian issued a price edict that listed maximum prices for goods, as imposed by the government. A live lion was listed as the most valuable commodity, worth a price that amounted to more than an average worker earned in sixteen years. Coliseum shows took the lives of tens of thousands of African animals through the course of Roman history.

The Periplus attests that an area of particular importance for the ivory trade was the Aksumite Kingdom, an ancient empire that thrived during the first ten centuries of the Christian era (100 – 940 AD). Its capital city of Aksum stood in the fertile highlands of (modern) northeastern Ethiopia in a region grazed by herds of forest elephants and white rhino. Describing commerce through the region, it explains that, “Into Aksum is brought all the ivory from beyond the Nile and the Kyeneion (modern Tekeze River) for transport down to Adulis.” It further states that “The mass of elephants and rhinos slaughtered inhabit the upland regions, though on rare occasions they are also seen along the shore near Adulis,” thus indicating that coastal elephants and rhinos had already been driven to extinction.

In his writings Pliny noted that during the reign of Augustus the Africans brought “. . . a large quantity of ivory, rhinoceros horn, hippopotamus hides, tortoiseshell, apes and slaves to the site.” He also refers to an inland group of people called Troglodytes (cave dwellers) who made their living exclusively from hunting elephants. Pliny called ivory “the most precious organic material on earth” and reports that as forest elephants were brought closer to extinction, new trade outposts further to the south, in present day Kenya and Tanzania, were established for the procurement of savannah elephants. “By 77 AD”, he writes, “. . . only India can supply an ample supply of tusks, as luxury has reduced all other stocks.” (Pliny, 8.4)

The Roman Gentry

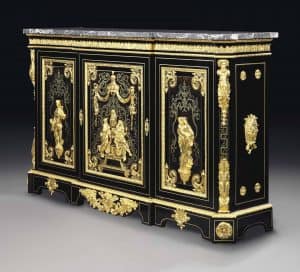

Wealthy Romans had both town houses and country villas, the furnishings of which were a display of prestige and wealth. By the first century AD, the elite classes had developed an obsession for extravagant ornamentation, and the Roman noble would proudly boast about what had been spent on exquisitely crafted furnishings. The most prized materials for furniture such as couches, chairs, beds and chests were exotic woods such as ebonies and blackwood (with burls being especially prized) and ivory. These materials were often inlaid with lustrous tortoise and turtle-shell veneers and mother of pearl. Part of the appeal of these exotic woods was their fragrant sap and Pliny reported that ebony wood-shavings produced a pleasing smell when burnt and that the Romans were importing “small thickets of ebony branches” to be burned as a form of incense.

Excesses of the Roman gentry and populace did not go on without criticism from certain philosophers and commentators who decried such extravagances as vain and excessive. Clement of Alexandria (150-215 AD), a Christian theologian of Alexandria wrote about, “the stupidity of luxury” and cautioned his readers on the excess usage “ . . . of easily cleft cedar and thyine wood, and ebony, and tripods fashioned of ivory, and couches with silver feet and inlaid with ivory, and folding-doors of beds studded with gold and variegated with tortoise-shell, and bed-clothes of purple and other colors difficult to produce, proofs of tasteless luxury, cunning devices of envy and effeminacy,” He advises that they “. . . are all to be relinquished, as having nothing whatever worth our pains.” (The Instructor – Book II, Ch. III)

Seneca remarked on the excessive prices of the most expensive imports when he wrote, “I see tables and pieces of wood valued at the price of a senator’s estate (1 million sesterces) and these are all the more precious when the surface is twisted with the outline of tree knots.” Juvenal, a Roman satirist in the first century AD, wrote that the possession of such luxury items had become so desirable and so excessive that he knew of a wealthy man named Licinus who had troops of slaves with fire-buckets stationed around his property to be ready to dowse the flames should a fire break out. Others hired guards to ward off theft. He further wrote, “. . . nowadays a rich man takes no pleasure in his dinner, his turbot and his venison have no taste, his unguent and his roses no sweetness, unless the broad slabs of his dinner-table rest upon solid ivory.”

When the Roman Empire finally succumbed to the greater strength of outsiders in the 5th century AD, one cause of its fall was the exhaustion of its supply chains of commodity goods, resulting in its inability to finance the training and supply of the large regiments of Roman troops needed to keep peace in the kingdom. No longer able to maintain its borders, it became prey to numerous invaders who occupied its lands and set up new networks of governance and trade. In the 7th and 8th centuries the rapid expansion of the Arabian Muslims inspired by Muhammad, the prophet of Islam, occupied many of the lands bordering the Mediterranean which had once been the domain of Rome. Along the eastern coast of Africa their influence was particularly strong because of the ancient ties already developed through their geographic proximity on opposite sides of the Red Sea. Since Egyptian times the peoples of Arabia and eastern Africa had been important trade partners and with the establishment of Islamic rule, this partnership became of paramount importance.

The Swahili Coast - The Arabs And The Africans