MAKONDE ART

Songhan-Hanrong African Art Collection Museum in Changchun, China exhibits 1,000 pieces of Makonde art – the largest collection in the world.

Wood Carving Artists of Eastern Africa

Perhaps the richest and most emotive cultural expression of the interplay between Dalbergia melanoxylon and its human users is the ever-evolving dynamic seen in the work of the Makonde carvers of Mozambique and Tanzania, African artists whose traditions reach back into their historic roots and ancient origins. The Makonde produce a form of sculpture that runs the gamut between ‘tourist art’, the mass production of popular styles for tourism markets, to that of the always-changing and truly inventive creation of new forms of expression.

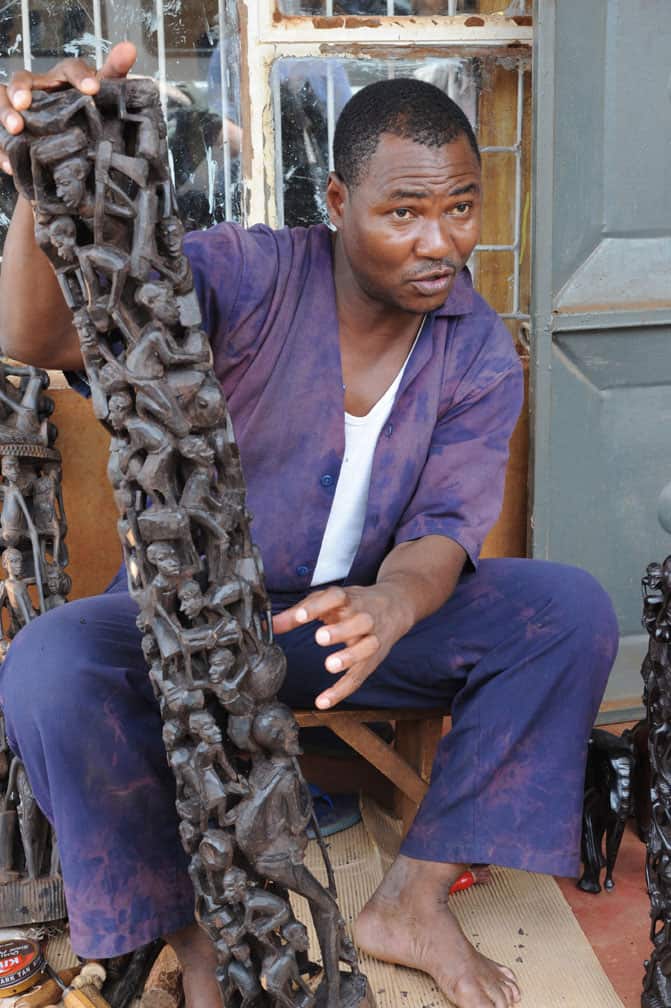

Using to advantage mpingo’s density and rich beauty, the Makonde have developed an art form that has been passed through succeeding generations, undergoing evolution into continually changing expression over time. Although in current times artists have had to adjust to using other woods because of the decreasing availability of mpingo, African blackwood has come to be identified with Makonde art at an essential cultural level, and some artists consider the wood as a projection of their own personhood. In many communities collectives of artists can be found, often gathered in the shade of a huge sprawling tree, carving roughed-out pieces of mpingo into forms that express the history, traditions and cultures of their native lands. Even into the present time, the Makonde artist will typically work seated on the ground, using only hand tools and supporting the work against a block of wood or a thigh, foot or arm.

In this section will be discussed the political and cultural history of the Makonde, the two of which are intricately interwoven. The Makonde response to the disruptive historical, economic and political events of the colonial era that have so shaped the African continent also shaped their artistry, leaving their imprint on each succeeding generation. Colonial occupation, the Makonde struggle for independence and a long and difficult civil war had a crucial influence on how they utilized, developed and embraced their art.

The Makonde of Mozambique

In 1497 the Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama rounded the southern tip of Africa – the Cape of Good Hope – and Portugal became the first European nation to open the long sought maritime trade route to India that had been the goal of Columbus in his earlier travels. As a result of this discovery Portugal established garrisons and trading posts along the eastern coast of Africa, eager to find gold, slaves and settlement areas for its own population. Their primary area of influence came to be known as Mozambique and was governed by Portugal from 1498 to 1975.

The Makonde who live in the north of the country are of Bantu origin and are thought to have migrated from the west into southern Tanganyika and northern Mozambique during the 17th and 18th centuries to escape Arab and colonial slave traders and the predation of other tribes. They settled on high plateaus abutting both sides of the Ruvuma River (the boundary between Tanzania and Mozambique), the Tanzanian Makonde on the Newala Plateau and the Mozambicans on the Mueda Plateau in the present province of Cabo Delgado. There they were able to remain in relative isolation because of the rugged terrain and water-poor environment.

The Mozambican Makonde were known for their fierce individualism and determined resistance to slave traders, and they established a reputation as formidable warriors in their struggle to maintain their customs and tribal coherence. High on their plateau they hid their villages in the most impenetrable parts of the forest and created thicket barriers through which they cut mazes of trails, concealing hidden spikes to prevent the entry of outsiders. They were called “the angry ones” because of their fierce demeanor and determination.

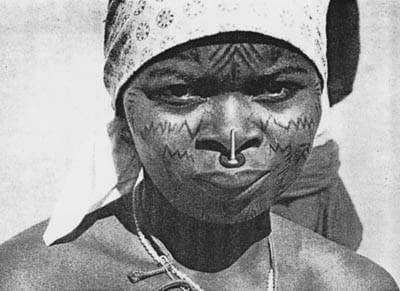

Adding to their fierce persona, they practiced a cultural tradition of bodily scarification, incising faces, chests and backs with various geometric patterns which were darkened by the rubbing in of charcoal. They also filed their teeth into sharpened points. Women of the tribe often wore an inserted plug of mpingo in the upper lip, considered to be a signature mark that indicated distinction and beauty. All of these practices were generally disbanded by common agreement after independence because of the new socialist state’s desire to eliminate class and tribal divisions, but on their high plateau in colonial days they helped the Makonde to create an ethnic identity.

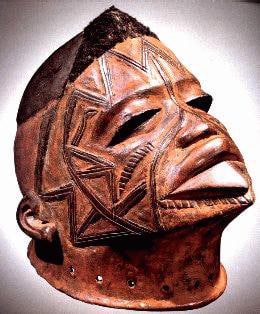

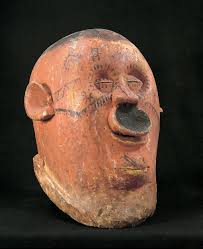

Although the Tanzanian Makonde developed somewhat different cultural practices from those in Mozambique, both are matrilineal societies and had long-established carving traditions, teaching their young men the techniques during initiation ceremonies. Some carvers produced functional objects like tools, implements and bottle stoppers, but the more artistically inclined were given the task of creating ritualistic helmet masks called Mapiko (singular Lipiko) and figurines for initiation ceremonies, which were sacred events. The masks were carved from lightweight woods like Ficus sycamorus (sycamore fig), and later burned. Traditionally only men were carvers and their work was kept strictly secret from the women of the tribe. In present times masks are also carved by women and are used in instructional gatherings and public plays and performances. They are made of a variety of different woods and can be found for public sale.

The Portuguese in Mozambique

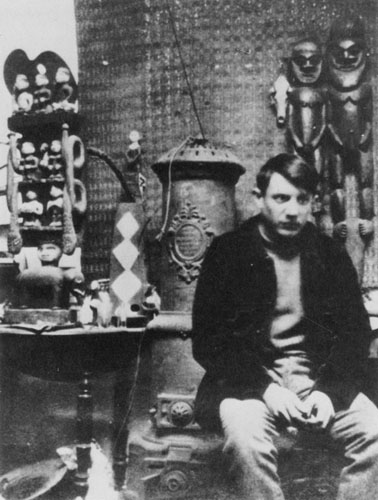

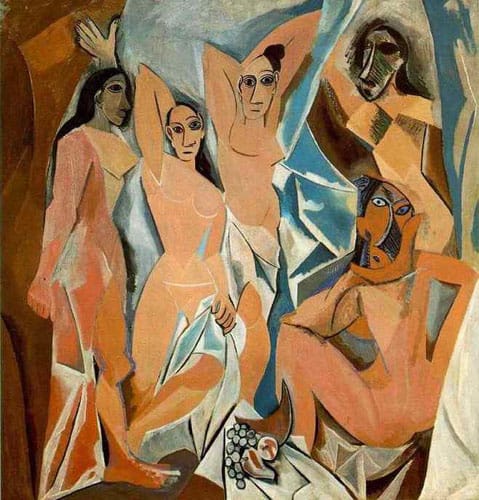

When ethnologists and explorers began to travel more widely throughout Africa in the 1800s, they collected many articles of traditional artwork which they brought back to Europe and displayed in public museums, thus preserving a history of early African art and exposing the rest of the world to the creativity of societies throughout the continent. Some of Europe’s most renowned artists, such as Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Henri Matisse were great admirers of African art. In 1906 Matisse bought a small African ‘Vili’ figure carved in the (now) Democratic Republic of the Congo and showed it to his fellow artist, Pablo Picasso. Picasso later remarked that it was only after wandering through exhibits at the Palais du Trocadéro, Paris’s ethnographic museum, that he understood the impact of such art. Picasso’s biographer John Richardson describes a visit that art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler made to Picasso’s studio in 1907, the year he produced his iconic painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, perhaps one of the most famous examples of modern art’s appropriation of indigenous art forms. There he found stacks of canvasses and “African sculptures of majestic severity” – A Life of Picasso, the Cubist Rebel 1907-1916.

Pablo Picasso’s 1907 creation Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is the seminal work that gave birth to cubism. It is generally agreed that cubism contains influences from African art, and in this case African masks. A close examination of the figure on the right shows the type of scarification that was widely practiced in Africa at the time and the stylized geometric arrangement of facial features that some African masks employ.

World War I on the Makonde Plateau

The Mozambique Makonde remained relatively isolated until the events of World War I, an international conflict that had ramifications for European colonial holdings throughout Africa. In 1917 the Portuguese, fearing invasion by German troops who occupied Tanzania on the north side of the border at the Ruvuma River, sent a large defense force to Cabo Delgado, and for the first time were able to penetrate the Makonde plateau. There they established a military garrison, a site that became the town of Mueda, and instituted a long period of colonization, cohabitation and foreign dominance.

Throughout Africa the establishment of European hegemony introduced systems of taxation that served to subjugate indigenous people and undermine local lifestyles, and Portugal was one of the most brutal colonial powers on the continent. Tribal kingdoms that had depended on their own agriculture and mutual barter now had to work for colonial overseers in order to produce cash incomes to pay the often harsh taxes levied on the population. In Cabo Delgado, the Portuguese imposed a hut tax on local families in order to conscript a labor force for building roads and growing crops for their troops. The road system thus established opened the way for the entry of commercial traders and missionaries, who had further influence on the native populations. For the Mozambican Makonde, the punitive taxes and forced labor precipitated a northward migration into Tanzania, where many of them sought employment in its sisal plantations. The proficient carvers in both of these groups, those who stayed in Mozambique and those who immigrated north, had an advantage because they became able to earn cash income by marketing carvings to the European colonialists.

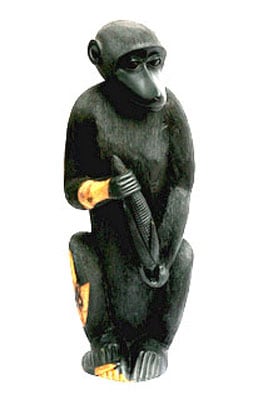

The carvers among the Makonde who remained on the Mueda plateau were quickly noticed by commercial traders and missionaries who realized the economic potential of their artistry and commissioned carvings, thus establishing the first commercial networks of distribution for their art. By means of this the carvers were provided an income to cover taxes and pay for domestic needs and were able to avoid the onerous work demanded by the Portuguese. These influences quickly expanded the range of carvings produced. The Portuguese could most readily market carved animals and figures representing Africans in their daily activities, carrying water, tending their children, or hunting and farming. This is a Makonde form that has since become known as Binadamu, a Swahili term that means ‘humankind’. Portuguese religious missions commissioned religious statuary of biblical images and crucifixes. Some missions hired carvers to work full-time on their staff and this provided families with a steady source of income and an education for their children.

Because of these developments, Makonde carvers began to establish cooperatives to more efficiently source materials and tools and to develop strategies to maximize their potential. The first Makonde on the Mueda Plateau to establish a carving cooperative was Nyekenya Nangundu from Miula village, a creator of mapiko masks who had been taught by his father and grandfather in the traditional style. Determined to help his people escape the brutality and poverty of the colonial system and reduce the onerous tax burdens they suffered, in the mid to late 1920s, he enlisted villagers who had not been trained in carving and taught them to carve the objects sought by colonialists. When Portuguese buyers expressed a preference for carvings made of harder wood, it was Nangundu who chose African blackwood and thus started the tradition that has tied mpingo to Makonde art ever since. Nangundu himself eventually abandoned farming and became a full-time carver and teacher.

During the next several decades Makonde art transitioned from a secret art for ritual use into becoming an economic and creative force in mainstream society and thus was established a career path for a much larger segment of the population. Carvers could obtain an artisan’s license which exempted them from forced labor and allowed them to work at carving full time. Colonial administrators and missions began to build up large collections of Makonde carvings and ran profitable export businesses, introducing Makonde art to the international community. Over the next century their imaginative skills developed three distinctive forms of expression. Binadamu was the depiction of realistic human and animal figures, Ujamaa was an expression of human connectedness and interdependence and Shetani were imaginative carvings depicting their spirit world.

Binadamu Carvings

Traditional Binadamu figures above. On the left is a carving of a soldier produced in 1920 by Mutisya Munge (his name is signed below the belt buckle), who first established a carving industry in Kenya by imitating the Makonde artists he met during World War I when he served with the British Carrier Corps in Tanganyika. After the war he produced many carvings of “Askari” (Swahili for soldier) and Africans in traditional dress and poses to sell to Europeans. Other Kenyans imitating the style gave birth to what is now one of Kenya’s most admired artistic expressions.

The Makonde in Tanzania

After WWII Tanganyika (its name before it united with Zanzibar after independence) was under British rule, a colonial power that offered better economic opportunities and was less oppressive than the Portuguese. The sisal industry in southern Tanganyika continued to attract thousands of Mozambicans because they could earn up to sixty times the salaries they were paid in Mozambique. As the Makonde made their way north to take advantage of the better wages, the carvers among them formed carving communities to supplement their income on the sisal plantations.

Norman Kirk was a New Zealander with economic interests in southern Tanganyika. During the 1950s he helped to establish a permanent carving cooperative on his lime and cashew nut plantation that was operative until his death in 1969. Kirk’s management style was fairly restrictive artistically because he required each artist to produce only one type of figure. His support, however, provided valuable income for many carvers who were sending money home to their families in Mozambique. By the late 1950s he had established a profitable export business. It was at his suggestion that the Makonde began to create chess sets and over time this particular genre grew to include highly imaginative stylistic designs that were sought after by art collectors.

Over the next few decades numerous Makonde travelled into Tanganyika, moving further and further north to larger metropolitan areas to seek markets for their carvings. Dar es Salaam, the capital, has one of the largest ports in eastern Africa and became the destination for many Makonde artists, who settled into permanent communities to take advantage of its marketing opportunities.

Left: Hand carved chess set made of Dalbergia melanoxylon and Polocarpus latifolius (African Yellowwood), c. 1950-60. The rook is a thatched hut, the knight a giraffe’s head, and the king, bishop and queen are each distinguished by their head gear. Right: Close up of figurines from another set offered by Christie’s Auction House, London, England. The queen is carrying a water jug on her head. As described in the Christie’s catalog : “An African-carved ivory and blackwood bust-type chess set carved by the Makonde of Mozambique, c. 1950.”

Carvers in Dar es Salaam

Mohammed Peera

Mohamed Peera was a sponsor of Makonde art who has become legendary among Tanzanian carvers. He was a third generation Tanzanian whose grandfather had immigrated to Zanzibar from India. As a youth Peera had dreamed of becoming an artist or a writer, but he was prevented from finishing school and instead became a promoter of art. In Dar es Salaam he and his two brothers opened a retail outlet in the city where they sold jewelry, precious stones and curios. When a Makonde carver walked into their shop one day looking for work, Peera asked what he could do and on finding out he was a carver, invited him to come to the shop the next day and use its facilities. This began a long relationship between Peera and numerous woodcarvers, who not only found a workplace in which to create but an outlet where they could sell their work. Within a few months of inviting the first artist, there were eighteen carvers producing work for his shop.

Important to their development was that Peera’s woodcarvers were free to carve whatever they wished, with Peera buying almost everything they produced and paying a premium for pieces that he considered particularly expressive and original. He advised artists to never produce pieces just to please him and to not copy each other’s work but to instead explore the limits of their own creativity and produce new and original pieces. In this way Peera inspired the birth of numerous stylistic innovations that separated Makonde art from simple repetitive production into an art form that is unique and expressive of personal creativity and innovation.

Stylistic Innovation - Shetani

It was under Peera’s patronage that the most imaginative of Makonde styles – Shetani – was born. Shetani sculptures are a glimpse into the spirit world of the Makonde, because they depict mythic figures that are said to live in extra-human realms, but still have interaction with and influence over human actions. This can be beneficent, but can also at times work to the detriment of those who come across their path. A Shetani spirit can represent an emotional state, a nature spirit or a devil. One Shetani sculptor describes what Shetani means to him: “It comes from dreams. We believe that when we sleep the soul goes out, away from the body. When we awake we can have many pictures in our heads and Shetani is one of the results.”

The originator of the Shetani style was Samaki Linkakoa, a studio artist in the Peera shop who regularly produced lifelike Binadamu images, but had begun to lose sales to other more proficient artists. Peera encouraged him to seek a more creative expression and the first such carving he brought to Peera sold the same afternoon. Thereafter Linkakoa abandoned realistic art and explored the vicissitudes of a creative expression based on the inner and imaginary worlds of the Makonde. His forms inspired a completely new expression for the medium.

Other artists began to emulate the style and it has been one of the most distinctive expressions of Makonde art into the present, with numerous permutations. The mpingo tree, with its small girth and often twisted branches, lends itself well to such sculptural forms. Mawingu is a style related to shetani which was originated by Clements Ngala, who had also carved in the binadamu style. Ngala had had an inspiration while watching early morning clouds and began to carve the ephemeral images he observed in the clouds, depicting abstract evanescent humans with featureless faces and abstract portrayals of natural objects.

Tree of Life, or Ujamaa

The sculptural form popularly known as ‘Tree of Life’ is called Ujamaa, and is attributed to Roberto Yacobo Sangwani, an artist associated with Peera’s workshop, whose first creation was one which depicted a group of wrestlers carrying a champion on their shoulders. As other sculptors adopted the theme, it became a genre that spoke of solidarity, mutual support, and most importantly, relationship. Ujamaa are generally tall sculptures in the round that tell stories about the interrelations of family, tribal communities and larger social entities. Its intertwined figures symbolize connectedness and mutual assistance from generation to generation, with each built upon the one preceding. It might be seen as an African depiction of a family tree, often headed by a female figure, reflecting the matrilineal structure of Makonde society. Sculptors can spend a year or more carving such intricate figures and the statues can stand up to two meters high, utilizing the complete trunk of an mpingo tree. In the 1960s and ‘70s, the Tanzanian President Nyerere’s Ujamaa Party adopted the art form as a national symbol of political unity.

Below are other Ujamaa style artworks. Carving on the left shows prominent use of sapwood to frame figures. On right, a kinship group in a different style.

To view an extensive collection of Makonde artworks and read biographical descriptions of some of the artists who developed the unique styles that have come to be associated with Makonde art, see the website of Sebastian Hansen.

The Freedom Struggle and Political Art

During the 1950s and 1960s, countries throughout Africa began to organize political opposition to colonial rule. Throughout Africa, groups of men and women had been thrown together in enforced labor camps and the associations formed in those camps became the very milieu within which grievances were voiced and organized resistance was born. Ghana, which had been colonized by Great Britain, was the first to gain self-government under Kwame Nkrumah in 1957, and Tanganyika achieved self-government in 1960 under the leadership of Julius Nyerere, with both transitions relatively peaceful. Mozambique, however, was not to achieve independence until 1975, following a bitter and debilitating armed struggle against Portugal. The Makonde were to play a key role in organizing resistance during the war of liberation.

By the 1960s, thousands of Makonde emigrants were working in Tanzania where they had been given the benefit of education and become multi-lingual. These Makonde, influenced by the vigor and commitment of the freedom initiatives that were central to political thinking in Tanzania, began to organize resistance to Portuguese rule in Mozambique. The party they founded, MANU – the Mozambican African National Union – was modelled after TANU, the Tanganyika African National Union. It organized in both Mozambique and Tanzania, and encouraged an inclusive membership, incorporating women and people of diverse tribal affiliations. The key political event that solidified the Mozambique struggle for independence took place on the Mueda Plateau in 1960, when a peaceful gathering of demonstrators, attempting to present their political grievances to the Portuguese administrator, was fired upon, causing the deaths of 600 people. This brutal event galvanized opposition and united Mozambique’s three predominant parties into one, which became known as FRELIMO. Despite being greatly outnumbered by the Portuguese, FRELIMO staged a 13-year war while at the same time organizing Mozambicans into communities that were self-protective and economically productive. In 1975 independence was achieved, and the party remains in power today. Makonde art became interwoven with these historical events, and it contributed, both financially and ideologically, to the success of the struggle and the formation of an independent nation.

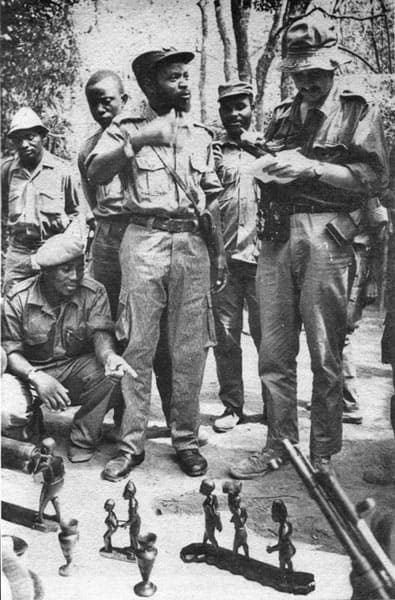

Many of the emerging nations of Africa, rejecting the capitalist philosophy of colonialism, turned to socialism, considering it to be a political ideology that more properly suited the communal nature of their societies. During FRELIMO’s armed struggle, part of its work among the people was to institute cooperatives for agricultural and commodity production in order to distribute work and profit among the people and help pay for its own military needs. One of its important initiatives set up cooperatives of Makonde carvers and instituted marketing networks for their art. Part of the profit went to FRELIMO and part to the cooperatives and their members. These artists, inspired by the momentous events unfolding in their country, were no longer willing to produce the simple replications and religious art that reflected colonial culture, and turned instead to carving statues that showed the reality of their history and culture and the type of socialist model that was being erected by FRELIMO. This art would be used as a teaching tool for the new nation. Images of African life and culture, the value of family, communal sharing and support were common themes, along with depictions of the brutality of colonial oppression.

Julius Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania, promoted Ujamaa carvings as a symbol of the essential values of African family and nationhood. He sent Makonde carvers abroad, in order to display their work as a voice that depicted the socialist values of Tanzania. His government donated land in the center of Dar es Salaam for the establishment of a cultural heritage center to promote the arts of Tanzania. Named Nyumba ya Sanaa (House of Art), it served as a training center for artists, as well as a retail shop to sell their work. The careers of many Makonde carvers and other artists were established and promoted through this center.

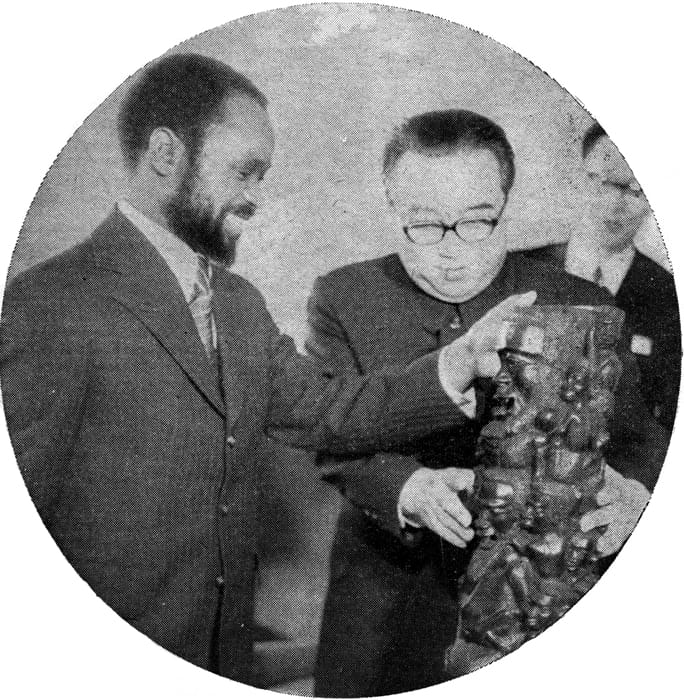

Left: 1973 – Samora Machel, military commander of FRELIMO and future president of Mozambique, is interviewed by his British biographer, Iain Christie, at a village carving cooperative in Cabo Delgado. Machel’s associate on his right is pointing out the blackwood carvings produced by the cooperative, which depict the oppressions of colonial rule. Right: 1975 – President Machel presents North Korean Premier Kim Il Sung with an African blackwood sculpture of the Ujamaa type.

The Kamba and Zaramo Woodcarvers

There are now estimated to be 60-80,000 woodcarvers in Kenya, and this development also has its roots in the Makonde tradition. The Akamba (or Kamba) are an ethnic group in Kenya which historically had acted as guides and porters for Arab and European traders, leading expeditions from coastal provinces into inland villages. Their long experience of exposure to multiple cultures and foreign contact gave them a broad experience of international contact. It also made them excellent soldiers, and during World War I they were enlisted by Great Britain to serve in Tanganyika, then occupied by Germany. One of the results of this contact was their introduction to Makonde woodcarving. A returning soldier, Mutisya Munge (see his Binadamu carving of a soldier above), impressed by the woodcarvings he had seen in Tanganyika, copied the style and passed on his knowledge to neighbors and family members.

Not only did the Ukamba quickly become excellent wood carvers, but their wide range of contacts enabled them to become successful in merchandising their art without relying on middle-men. Their numbers quickly expanded as they took advantage of the increased trade that began in the 1950s. By the late 1990s the Kenya woodcarvers had built the largest export trade of this kind in Africa, generating around US $20 million yearly. Within Kenya, blackwood was once abundant, but because of the swift expansion of this export trade, as well as increased international utilization of the timber, commercial stands within the country no longer exist and carvers either import mpingo from Tanzania or utilize other woods as a substitute carving medium, now diversifying into using over fifty other species.

The Zaramo is another group which utilizes Dalbergia melanoxylon in artistic woodcarving. Its people live in the coastal area of Tanzania and are the largest ethnic group in Dar es Salaam. Like the Makonde, they had an indigenous carving tradition and began to produce art for export during the colonial era. Salum Chuma was a highly gifted Zaramo artist in Mohamed Peera’s workshop and he traveled abroad several times representing the Tanzanian artistic community.

Mwenge Woodcarver's Market

Makonde carvers typically work while seated on the ground, stabilizing the workpiece against a foot, leg or the ground itself.

The Mwenge Woodcarver’s Market in Dar es Salaam is the largest retail outlet for Makonde carvings in Tanzania, and has enabled many carvers to make a living from their art. It contains over 200 shops and the artists who exhibit their work can often be found on the grounds, carving a new creation or bringing a piece to its final sheen. Tourism is a huge business in Tanzania, and over a million visitors arrive yearly. It is home to Mt. Kilimanjaro, Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Serengeti National Park, Selous Game Reserve and numerous other natural wonders. Since Dar es Salaam is the gateway into interior Tanzania, many tourists visit its markets to purchase souvenirs of their stay in the country.

Female Carvers Break Tradition

The story of Mozambique’s liberation from colonial rule developed side by side with a story of the liberation of its women from restrictive societal roles. During the war for independence, women were actively recruited by FRELIMO as soldiers and underground spies and began to take on more active roles in many sectors of social and political life. In the present era a few women are breaking the male-only carving tradition and are establishing reputations as world-class artists. Mwandale Mwanyekwa, who works in wood, stone, bronze, clay and cement is one such woman.

Born in 1978 in Dar es Salaam, she was adopted by her grandparents and spent her early years in Mtwara in southern Tanzania. Five generations of her matrilineal ancestors had been potters and she was encouraged at an early age to develop her creativity. Her great-grandmother taught her carving and her grandmother allowed her to use the modelling clay in her own studio, while her grandfather taught her his skills as a carpenter. In 1997 after graduating from secondary school, Mwandale attended Bagamoyo Sculpture School, where she learned the art of sculpting in wood, bronze and cement. Since completing her studies she has received commissions from a number of international organizations and exhibited her work in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Europe and the USA. Her work is on display at the Changchun Sculpture Museum in China and the Vergnacco Sculpture Park in Venzia, Italy. In 2008 she worked with the “Women are Creators” group to organize an exhibition to honor Internationals Women’s Day at the National Museum in Dar es Salaam. Some of her pieces reflect themes that call attention to the problems of domestic violence and breast cancer.

Mwandale remarks, “I think I was born as a Sculptor, The genes of sculpture inherited from my grandparents helped me to sharpen my talents and skills”. “Art is in my blood…it is not something I am doing because of money or because of lack of work. It’s something you need to have a passion for. You need to love it.”

The Changchun World Sculpture Park

The Changchun World Sculpture Park located in Changchun, Jilin, China is a theme park opened in 2003 to celebrate the art and sculpture of the world with the theme of ‘friendship, peace and spring’. The park covers an area of 92 hectares including 11 hectares of lakes, and features artistic works from 130 countries, including both Eastern and Western cultures. On the park grounds is the Changchun Sculpture Museum with a large exhibition area featuring Makonde art. The sculptures were donated by Li Songshan and Han Rong, a couple who worked in Africa for more than 40 years and collected over 10,000 pieces of African art, never reselling any of them. In an interview with the couple, Li commented that, “It’s unreasonable for art academia to claim that there is no modern art in Africa. Makonde art dates very far back from now, but I think it’s also a modern art.” Han said, “Ebony is as precious as ivory. Its productions are highly valued and prized in the global market, and it is the irreplaceable top choice for carving.” The couple wishes to leave a legacy that will “give more people a chance to learn about African culture and art.” About 1,000 Makonde creations are exhibited in the museum. A photograph of the Makonde exhibit can be seen at the top of this webpage.

Below: Original Makonde carving from Tanzania entitled “Christmas Boat.” Horizontal portion is carved from enormous mpingo trunk and shows sapwood and end grain.