ORNAMENTAL TURNING

Kaleidoscope above is fashioned from African blackwood on a specially adapted lathe.

300 Years Of Ornamental Turning

In modern times, African blackwood is also the wood of choice for Ornamental Turning (OT), a twentieth century extension of an art form that had its roots in Europe. Whereas ‘plain turning’ is the production of rounded objects, such as bowls, plates, and vases on the lathe, ‘ornamental turning’ adds embellishment to a smoothly rounded piece by introducing external cutters that make precise cuts at intervals around the piece. Such symmetrically placed cuts, executed by a variety of cutting tools, can produce geometric patterns of ornamentation of amazing complexity and beauty. Similar to its use in manufacturing musical instruments, the density, oiliness and tight grain of African blackwood make it one of the most highly sought woods to execute this craft.

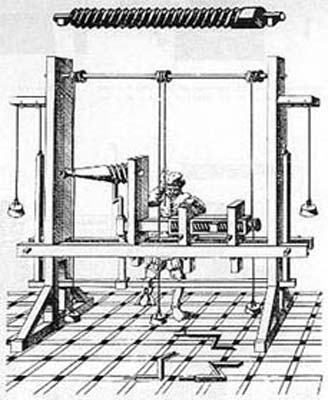

The history of the lathe dates back to the era of ancient Egypt, but as the world entered the age of industrialization, its use as an instrument that could produce other tools as well as functional and artistic objects was widely recognized, leading to its modernization and increased complexity. One of the earliest mentions of ornamental turning comes from the letters of Martin Luther (1483-1546) who mentioned the practice as providing him a means of livelihood. Leonardo da Vinci’s successor as engineer to the French court was Jacques Besson, who invented an OT lathe driven by a bow. An illustration of his machine, dated to 1578, is thought to be the earliest known drawing of an OT lathe.

Because of the expense of the machines required for ornamental turning, few ordinary craftspeople were able to buy them. They were purchased therefore by the aristocracy of the countries where they were produced. The art of ornamental turning became the domain of the aristocracy, a leisure time activity to fill their hours with creative work. Women as well as men took up the hobby, producing objects made of wood, ivory and a variety of metals.

The first books to describe ornamental turning were written by L’Abbe Charles Plumier in 1701 and Joseph Moxon in 1703, while a more elaborate treatment of the subject matter was written by L. E. Bergeron in 1796, who directed his remarks towards the aristocracy. In the 17th and 18th century ornamental turning became a hobby for Tsar Peter the Great of Russia, the Prussian Kings Frederick III and IV, Louis XV and XVI of France and several kings of Denmark. Both men and women practiced the craft, and European museums have preserved their artistry, produced in a variety of materials such as ivory, wood and metals, and often inlaid with precious stones.

Ornamental Turning Of Peter The Great

Russia’s Peter the Great (1672-1725) is known for his commitment to technological progress and he was single-minded in building a groundwork that would bring his country into the modern age. His travels throughout Europe to seek out inventions and the latest industrial techniques are well-documented. He has a particular connection to OT because his personal hobby and avocation was lathe work. One of his contemporaries described his daily routine in this way, “The sovereign wakes up very early. From three to four o’clock in the morning he attends the secret council. Then he goes to the shipyard and keeps his eye on shipbuilding. He often works himself, as he knows the job in detail. At nine or ten o’clock he is busy with the turner’s work, in which the Tsar is so skilled that (he) would be in no way inferior to anybody.”

Because of this personal interest in turning, he ordered the translation of Plumier’s seminal book and employed the great Russian engineer, Andrey Konstantinovich Nartov (1683-1756), to design and build a number of lathes modelled on those discussed in the book, including one adapted to executing OT designs. Nartov was a scientist, military engineer, inventor, sculptor and a member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. In 1718 Peter sent Nartov to Prussia to introduce his lathe design to King Friedrich-Wilhelm I of Prussia, gifting the King with a goblet and snuff box that Peter had designed and turned, as well as a fully functional lathe. Nartov was invited to stay for a month and a half to teach the King the art of turning. In 1720 Peter gifted a lathe and a collection of turned objects to France’s Louis XV and Nartov spent a year there teaching the technique of medal turning. The Head of the French Academy wrote to Peter that he had never before seen such marvelous turning work. The lathe and turned objects presented to Louis XV are now in the Museum of National Arts and Crafts in Paris.

It is unclear as to whether African blackwood was imported to Russia in czarist times. The country’s carving artisans and turners during this era prized fossilized mammoth ivory, walrus tusks, seal bones or elephant ivory as a material of choice, and the artform itself became known as bone-carving. The aristocracy and upper classes often requested bone or ivory to execute their commissions and souvenirs made of these materials were popular as gifts to important people.

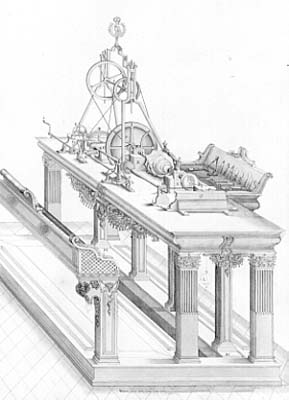

John Jacob Holtzapffel

A half century later in western Europe a French-born tool maker by the name of John Jacob Holtzapffel moved to London in 1787 to establish a tool making business. There he further expanded the capabilities of the lathe by designing and manufacturing machines that enabled a range of capability and refinement surpassing all previous machine lathes. Between 1795 and 1914 Holtzapffel and his heirs produced 2,557 lathes. The high quality of the materials chosen and precision of machine work involved in their production are a testament to the strict standards adhered to in their manufacture. Because of their expense, Holtzapffel lathes, like the Nartov machinery before them, were sold to the aristocracy of Europe, thus continuing the tradition of OT as a leisure time hobby for the upper classes. Between 1812 and 1848, for instance, the Earl of Harborough bought nine Holtzapffel lathes.

In addition to their unsurpassed machine tools, the Holtzapffel family left a second legacy – a publication in five volumes entitled Turning and Mechanical Manipulation, Intended as a Work of General Reference and Practical Instruction, on the Lathe, and the Various Mechanical Pursuits Followed by Amateurs. These books contained 3,000 pages and 1600 illustrations and were intended as an overview of all mechanical arts of the day. Today, Volumes IV and V of this series are known as the “Bible of Ornamental Turning” because of their wealth of information about all aspects of the craft. The writing of this monumental work was initiated by John Jacob’s son, Charles, and continued by his grandson John Jacob II. For the OT artist it describes the intricacy of the Holtzapffel machinery and tools, attributes of particular woods that are best suited for the work and directions for the methodology needed to achieve mastery of the craft of turning.

Holtzapffel considered African blackwood (which he also referred to as Black Botany Bay wood) as the most highly prized wood for ornamental turning. In Volume V of the Holtzapffel books are comments extolling its superior properties. They are reproduced below along with his commentary on the use of cocuswood, boxwood and Diospyros crassiflora from western Africa (which he called ebony). His remarks indicate that during his time, cocuswood, once prized for woodwind instruments, was already becoming threatened.

Regarding woods suitable for ornamental turning, Holtzapffel wrote, “African blackwood, known also as Black Botany Bay wood, unquestionably heads the list and stands next to ivory in all particulars. This wood when the log is first cut up or opened and sometimes its seasoned pieces when they are turned to the shape of the work, frequently shows some figure and is interspersed with dark grey streaks, but these marks soon disappear from all finished surfaces which then become of an absolute intense black. The grain is remarkably close, uniform and silky, and although African Blackwood is among the hardest of the hardwoods it is almost devoid of silex and hence it is less destructive to the edges of the tools than many softer, like ebony, that are more or less charged with it. This material is in every way suited to deep or shallow cutting and is especially valuable for surface patterns, the facets upon which acquire a brilliant polish from the cut of the tool alone. African blackwood is however exceptionally uncertain and wasteful in its first preparation from the log, and the great majority of sound pieces that may be obtained do not exceed about two inches in diameter, three to four inches are considered a large size, and five inches diameter a rarity; still larger pieces when found are invariably unsound in the center, but that is often of little consequence, as in a base or other large part of the work such faults are covered and concealed by the other portions they support. The largest and most promising logs are generally vexatiously deceptive in their yield in point of size, hence, the use of this wood plankways to which it is better adapted than most is often imperative.

“Many of the hardwoods are attacked by the worm, of which the author once released a living specimen from the heart of a log of kingwood; this creature was about two inches long with a hard horny head and a dusky white, soft, articulated body, quite half an inch in diameter, tapering both ways to head and tail, and it was yet vigorous although as the log was well seasoned the tree must have been felled a very considerable time. The variety that attacks the African blackwood is usually much smaller, and is apparently not more than a quarter the size of that mentioned, nevertheless one specimen found in cutting up a log in the author’s workshops a few months since, dead in its self-excavated tomb, measures four tenths of an inch across and also in the length of its head, and its desiccated body shows that it was not inferior in size to its live congener. The worm channels, long round cavities filled with a light-coloured loose powder, are not infrequent and much wood has to be rejected on their account, but sometimes there is no external indication of their locality in the solid wood, and they are occasionally met with in the interior of blocks apparently perfect. These cavities are all small and filled with compact powder, and they are probably vacated feeding grounds compressed by the subsequent growth of the tree; the wood so perforated is not to be despised unless the fault occurs upon some portion necessary to the outline and so cannot be turned away, for these smaller cavities are not usually extensive, and generally when they make their appearance in the course of preparing the work, they also disappear – as abruptly, while the material immediately around them is often of the best and silkiest quality. Ebony as an alternative blackwood cannot be recommended, it is inferior in color, fibrous or woolly in texture, and very liable to splinter, hence it disappoints in all ornamental turning and in addition it is very destructive to the cutting edges of the tools, while its turnings are dusty, penetrating and disagreeable.

“Cocoa wood or cocus when of fine quality, increasingly difficult to be met with, is but little inferior in texture to the African blackwood. It ranges through all shades of colour from a lightish yellow brown to a rich dark brown, and all when freshly cut possess some figure; these markings nearly disappear in the lighter varieties and entirely in the darker and better qualities with exposure, and the surfaces of finished works soon acquire nearly or quite a uniform tint, the lighter streaks attaining the color of the darker. Pieces of large diameter may occasionally be met with, but in these the heart is rarely sound, and unless the center is covered by some other portion of the work it has to be hollowed out and filled with a smaller sound piece. Cocoa wood varies in density, and the heaviest which is also the darkest is the best, it is perfectly suited to bold edge cutting and for surface patterns to either of which its final uniform color lends great advantage.

“The ornamental turner is largely indebted to Boxwood, and in no case more so than for the excellent and time-saving practice of making experimental trials of portions of plain and complex works, to be afterwards carried out in more valuable material. It may be obtained of all sizes to about ten inches diameter; its cohesion is scarcely sufficient for delicate permanent works, while its purity so readily soils that it is seldom employed for larger and stronger ornamental turning to be left from the natural wood; but these works may be dyed black on their completion (page 575, Vol. IV), to be then polished with the brush, and thus boxwood conveniently serves to supply the deficiency of size inseparable from the other harder woods.”

Ornamental Turning In The Modern Era

The 19th century was known as the zenith of the ornamental turning lathe in Europe. With the advent of the industrial revolution bringing its abundance of new technologies and vehicles of transport, the upper classes were able to expand horizons and find new outlets and objectives for creative and leisure activities. Holtzapffel lathes became museum pieces or wasted away in family attics. Some were melted down so the metal could be used for the war effort during World Wars I and II. The craft and machinery of ornamental turning began to fade into obscurity.

However, with the rise of the Arts and Crafts movement in the late 20th century creative woodturners found new markets for their artistry and reinvestigated the exquisite artistry practiced during the era of monarchical rule in Europe. In a notably synchronous confluence of thought, artists from Great Britain, the USA and Russia rediscovered the art of the ornamental turning lathe and gave it new life by adapting its techniques and machinery to modern times. This dedicated group of artisans and machinists are carrying on the OT tradition, inspiring the craft with a new creativity and imagination that integrates the use of nature, architecture and symbology, producing works of refinement and beauty. They are again creating work that is without parallel in the production of turned objects.

In Great Britain wood turners organized into a group called the Society of Ornamental Turners, sought out abandoned Holtzapffel lathes and put them into active use. In 1976 a US publication called Fine Woodworking published an article about an American woodturner, Frank Knox, who had acquired a Holtzapffel lathe and was producing exquisite artwork. When US machinist Ray Lawler read the article he determined to produce a modern, motorized (rather than treadle-powered) version of the lathe, using illustrations in the Holtzapffel books and taking measurements from Knox’s lathe. Several other US machinists, such as Lindow Machine Works, Fred Armbruster and Paul Cler have also manufactured machines with various capabilities that have enabled American woodturners to produce new and unique artwork. In 1995 Ornamental Turners International was organized to serve as a focus for ornamental turning in the US.

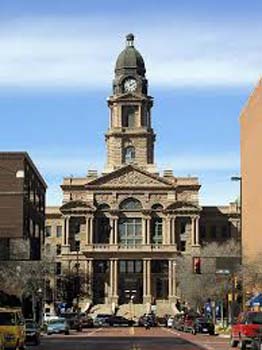

OT Artistic Replications Of Architectural Structures

Below is the work of three ornamental turners who have created reproductions of impressive architectural sites. Each of these artistic pieces is comprised primarily of Dalbergia melanoxylon.

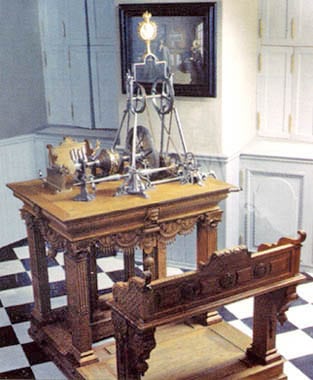

Valeria Mokeeva And The Petropol Gallery

In 1990 a similar Russian group of artists and technicians associated with the Petropol Gallery of St. Petersburg became intent on resurrecting the art of ornamental turning that Peter the Great had developed more than 250 years earlier. Similar to the US enthusiasts who reinvented the Holtzapffel legacy, the Russian group undertook the reconstruction of a lathe produced by Andrey Nartov in the workshops of Czar Peter. The original lathe had been destroyed by fire in 1747, but Nartov’s book Theatrum Machinarium (which had only been recently been rescued from obscurity) contained descriptions, diagrams and illustrations as guidelines for a reconstruction of the complicated piece of machinery. Led by the artist Valeria Mokeeva, who had founded Petropol Gallery, and supported by the State Hermitage Museum and the Russian Academy of Sciences, the group included researchers, architect–restorers, designers, mechanics, carpenters, sculptors and turners.

Between 1990 and 1993, under the academic guidance of Dr. V.Y. Matveyev, chief curator of the Hermitage, they painstakingly produced an accurate reconstruction of Peter the Great’s ceremonial medallic-copier lathe, as designed and executed by Nartov between 1717 and 1721. When the lathe was completed, it was found to be so accurate that the medallions it could produce were almost identical to those in the old court collections. Many of them were awarded to important visitors and guests of the city. As had been popular in czarist Russia, the Petropol artists work primarily in Siberian mammoth ivory, bone and wood. In modern times they are seeking to re-popularize the use of mammoth ivory as a substitute for elephant ivory.

In 1993 an exhibition honoring their achievement opened at the Hermitage. It was entitled “Theatrum Machinarum, or the Three Epochs in the Art of Bone Carving in St. Petersburg.” The collection featured the modern medallic-copier lathe produced by the Petropol group along with artwork they had manufactured on the lathe. The exhibit served as a means of reeducating the public concerning the great artistic contributions that had been made under the reign of Czar Peter.

The Petropol collective also produced impressive architectural pieces. In 1994 its artists created a “Triumphal Arch” of mammoth ivory and gilt bronze patterned after the Triumphal Arch in Moscow, which was presented in appreciation to US philanthropist Ted Turner by Boris Yeltsin. In 1984 Turner had organized The Good Will Games, an international sports competition to allow performance athletes to compete, since many had lost the opportunity after the political problems surrounding the Olympic Games of the 1980s. In 1994 the Good Will Games were held in Russia and Turner was presented with the Triumphal Arch during a ceremony at the games.

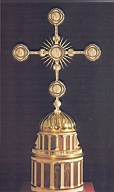

During the last year of his life in 1725, Peter created an artwork known as “The Life-Giving Cross with the Apostolic Faces on the Arc” using the original lathe produced by Nartov. It has medallions of saints and the twelve Apostles manufactured on the lathe. Peter’s original creation has been lost, but because it is carefully described in Nartov’s book, the Petropol artists under the supervision of Mokeeva were able to recreate, over a period of 18 months, a reconstruction. It is considered a homage to the monarch, revealing the uniqueness of his personality as expressed in the aesthetic and technical brilliance of the artwork which stands over six feet tall. This reproduction is now in St. Peter and Paul’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg. In 1996, on the order of Moscow Kremlin Museum, Valeria Mokeeva also made a replica of Peter the Great’s “St. Andrew” medallion, which was presented as a gift to Swedish king Karl Gustav XVI in the Kremlin.

Ornamental Turning Essay By James Harris

Ornamental turning consists of a wide variety of techniques for producing decoration upon the surfaces of turned objects. Since African Blackwood is in the rosewood family, it contains a high proportion of resins and oils as is typical of this family of hardwoods. This natural oily quality, along with the extremely fine grain texture, produces excellent results when it is used for ornamental turning. A highly polished surface may be obtained with a very carefully honed cutter.

Blackwood may be used for the main body of a piece or for trim details in combination with other woods. A ridge or a rim will hold its shape without breaking with even the most delicate cut executed upon it. The uniform, unfigured surface color, a dark plum brown/black, offers no distraction to compete with the geometrical patterning created by the technique of ornamental turning. It is in the same category as elephant ivory, which was once used in the craft in the Victorian era, as a material whose even coloration and smooth texture best shows off the effects of the decoration.

Blackwood also exhibits a flowery fragrance as it is being cut. This is a result of the volatilization of some of the oils it contains. Its lower content of silicates and other abrasive minerals (which are found in other woods such as ebony) keeps it from dulling the cutters as quickly. This allows the turner to work for a longer period of time before the cutter must be re-sharpened. In sum, African blackwood is a delight for the woodturner to utilize and must be marked as one of the finest hardwoods in the world for fine lathe work.

Even though the utilization of blackwood by ornamental turners represents a very small proportion of the commercial harvest of the wood each year, it plays an indispensable role in the execution of this craft and its loss would be keenly felt. Wise management and conservation of this remarkable resource can insure that it is available for future ornamental turners to render their particular creative magic, as well as continuing to play its vital role in the East African ecosystem. James Harris’ Ornamental Turning website can be seen here.

Woodwork above is from the gallery of James Harris, co-founder of the African Blackwood Conservation Project.