Dalbergia Melanoxylon In Woodwind Instruments

If you have ever heard the mellow tones of a jazz or classical clarinet solo, you have been listening to the natural sound of an instrument made of Dalbergia melanoxylon. The modern woodwinds that are constructed from the wood are clarinets, oboes, bagpipes, piccolos and some recorders and flutes. Musicians who play these instruments attest that there is no material comparable to the wood to produce the particular timber and pitch that are valued in the production of tone. Manufacturers as well regularly attest to the irreplaceability of the timber because the particular combination of properties that make it the ideal medium for woodwind manufacture have been found in few other tree species. Yearly use of the wood by the instrument sector is modest – an estimated 4.5% of its total usage.

Although the number of blackwood trees utilized by instrument manufacturers has remained relatively constant during the modern era, the industry has been heavily impacted by its increased demand from other sectors, and has had to turn to other options in order to compete. The use of alternative tonewoods, veneers and man-made materials, along with the sourcing of timber from certified forests, have all helped to reduce demand for African blackwood and other threatened tree species. In this section is a brief historical overview and discussion of the instruments of modern times that utilize African blackwood in their manufacture.

Wind Instruments in Antiquity

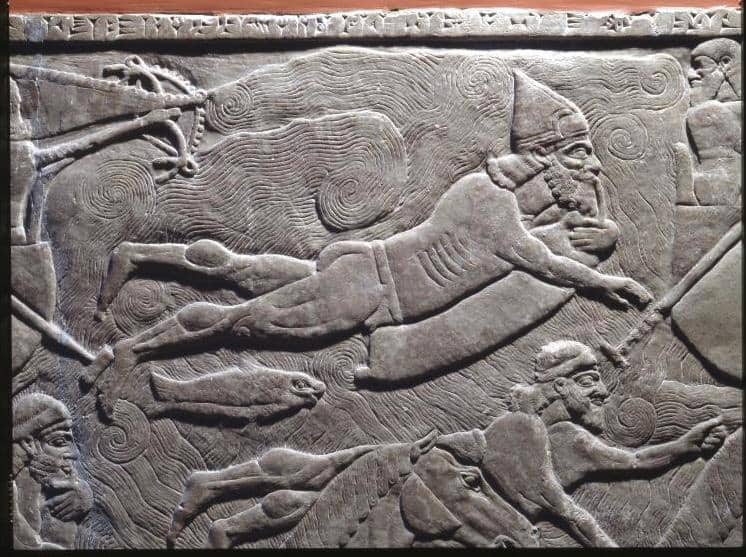

Music has accompanied the human journey since its earliest beginnings, with the flute as one of its oldest instruments, probably because a flute could be fashioned of numerous hollow materials which are plentiful in the natural world. Ancient flutes were made of animal horns and tusks, bones, conch shells, bamboo, cane and tree limbs and trunks. The traditional Australian aboriginal didgeridoo is made from a eucalyptus branch or trunk that has been hollowed out by termites, which only eat the core. Early prototypes of modern trumpets, horns, recorders and reed instruments can be found in many cultural traditions, fashioned of such materials into unique stylized forms.

The earliest musical instruments yet found have been in European Stone Age caves. Dating from about 50,000 years ago a marked increase in the diversity of cultural artifacts began to emerge in the archeological record. In Europe this was dated to a period when it was occupied simultaneously by the last Neanderthals and the first modern humans, and the first art appeared, along with indications of religious and spiritual behavior such as burial and ritual. Flutes fashioned of hollowed out mammoth ivory and swan bone, the oldest of which date to 42,000 – 43,000 years ago were excavated near Ulm in southern Germany. The archaeological site is near the Danube River, thought to be a key corridor for the movement of humans and their technological innovations into central Europe during that era. Similar flutes dated to around 32,000 years ago have also been found in rock shelters at La Roque and Les Roches, Dordogne, France.

The Trumpets of Tutankhamun

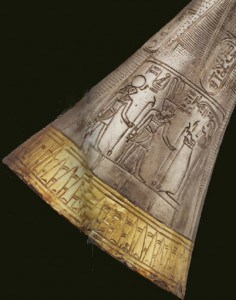

A more modern but also impressive find came from the tomb of Tutankhamun. In 1922 when Howard Carter opened the tomb of the boy-king, he uncovered an uncommon array of treasures that he described as “wonderful things.” Two of them were metal military trumpets, one of silver (the earliest specimen of a silver trumpet ever found) and one that is yet to be analyzed, of bronze or copper. Only three such instruments had ever been found in the tombs of pharaonic Egypt.

Howard Carter wrote of finding the silver trumpet in his publication about the tomb: “Beneath this unique lamp, wrapped in reeds, was a silver trumpet, which, though tarnished with age, were it blown would still fill the Valley with a resounding blast. Neatly engraved upon it is a whorl of calices and sepals, the prenomen and nomen of Tutankhamun, and representations of the gods Re, Amen, and Ptah. It is not unlikely that these gods may have had some connexion with the division of the field army into three corps or units, each legion under the special patronage of one of these deities – army divisions such as we well know existed in the reign of Rameses the Great.”

An early attempt to play the silver trumpet at a royal gathering before King Farouk of Egypt resulted in its shattering because of the use of an inappropriate mouthpiece. It was subsequently repaired and in 1939 a second attempt to sound both of Tutankhamen’s trumpets was made by James Tappern and broadcast internationally on the BBC. Listen to this performance here.

Wind instruments And The Industrial Revolution

Such ancient finds attest to the inherent nature of the human love for music in almost every culture on earth, and in modern times its influence is pervasive. The artistry of the wind instruments used in today’s orchestras is a product of the cultural and industrial revolutions in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries. This era brought not only technical innovation but an artistic awakening that gave us the symphonic masterpieces created by musical geniuses such as Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Chopin, Beethoven and Wagner. Their music demanded instruments with a greater range and more vibrant tonality, and in the great symphonic orchestras which performed their works, each instrument had to hold its own among dozens of other competing instruments. To this end the instrument makers of the era introduced new refinements and created entirely new instruments to produce music of such tone and timbre as to execute and enhance musical scores written by the composers of the period.

On the industrial side, instrument makers took advantage of improvements in metallurgy, machine tools and the wood turning lathe. Instruments once made by hand could be produced with a never-before-achieved precision. Metals could be molded and delicate fittings produced to enhance the sound of both wood and metal instruments. The invention of a valve mechanism for brass instruments was a major achievement because it allowed a regulated control of airflow through the instrument. Until the early 1800’s variation of pitch in horns and trumpets was regulated by the cumbersome means of using the hand on the bell or the introduction of crooks into the tubing – this is the reason for the many oddly shaped horns of antiquity. The combined creativity of industrialists and musicians have overcome many deficiencies and produced the diversity and technical excellence of the instruments of modern times.

The Stölzel Valve

Friedrich Blühmel was an employee working in a mining operation near Berlin who had also become skilled as a trumpet player in the mining company band. During his workday Blühmel could observe the workings of the steam engines that were used to pump water from the mines and to control the supply of air to blast furnaces. Through his observation of their valves he extrapolated that a similar mechanism might be built to control the supply of air in a trumpet tube by the introduction of a similarly constructed valve. Such an invention which would be able to divert and control the flow of air, he imagined, could shift the instrument from one key to another, thus extending its range. Heinrich Stölzel, a Berlin horn player and instrument maker was experimenting along the same lines and entered into collaboration with Blühmel. Together they produced a design for a spring-controlled slide-valve mechanism that produced a continuous musical scale in a range of almost three octaves for both trumpets and horns, a capability never before achieved. They applied for a joint patent in 1818 and the invention, which was widely accepted, became known as the Stölzel Valve.

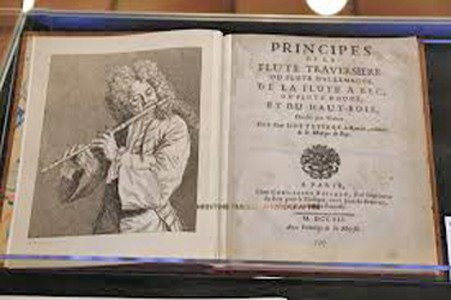

The Boehm System

The artist-engineer who had one of the most pervasive influences on the development of the artistry of modern woodwinds was Theobald Boehm, a celebrated Royal Bavarian Court composer and musician who was born in Munich in 1794. Because of his imaginative influence he is sometimes referred to as the ‘inventor of the modern flute’. His creativity was inspired by a concert he heard in 1831 by Charles Nicholson, who played a flute he had built himself with larger tone holes, an innovation that produced a greater volume of sound than the traditional flute. Inspired by the possibilities suggested by Nicholson’s performance, during the next 15 years Boehm experimented along several lines, i.e., the introduction of metal rings fitted around the tone holes so that the enlarged holes could be easily covered by the fingers, the diameter and shape of the central bore, the location of tone holes at acoustically optimal points and the opening and closing of keys. His innovation has had far-reaching, industry-wide application, and has been adapted to the oboe, clarinet, saxophone, piccolo and other wind instruments. Patented in 1847, it came to be known as the Boehm system. In 1868, Boehm submitted a manuscript to a publisher entitled “The Flute and Flute Playing: In Acoustical, Technical and Artistic Aspects.” He described it as containing, “. . . the history of all my work and all my experience during a period of 60 years . . .” It was published in 1871.

Instrument Woods

Similar to the acoustical and performance improvements for wind instruments that were enabled by industrial technology, instrument makers also sought out tone woods that would be more adequate for professional performance instruments. The range of notes and depth of tone needed could no longer be produced by a long hollow tube with holes and a mouthpiece, but rather needed a precisely machined cylinder outfitted with an intricate array of metal rings and fittings in order to yield orchestra-quality music. Therefore the woods used had to be extremely dense and chip resistant to accommodate the milling of screw threads and precisely placed holes needed for attached screw fittings and metal rings. They needed to be moisture resistant to hold up to the playing requirements of long performances without warping. In addition they had to possess the mysterious quality of ‘tonality’ – the ability to produce a sonorous and penetrating sound that could be sustained and hold its own. For orchestral use, the range of woods suitable for such sophisticated instruments narrowed to a precious few.

Nineteenth century English flutes – Above assortment of wooden flutes from England shows the assortment of materials available in Europe for instruments in the nineteenth century. Top flute is made of boxwood, second of cocuswood, third of ivory and bottom of boxwood. Warpage of boxwood can be seen on the lower flute.

European woodwinds had traditionally been made from European boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), because it was one of the heaviest timbers available within Europe. Although its density made it useful for woodwind instruments, its tendency to warp over time, even if it had been well dried, was a limiting factor. In addition to its small size and slow rate of growth, its light tan color also became a detriment because modern tastes had turned towards darker toned species. A wind instrument of boxwood was easily soiled through years of use.

When trade routes to foreign ports began to be established during the colonial period, numerous new hardwoods from tropical countries, noted for their density and machinability, were tested and one was found to surpass all others – Brya ebenus or cocuswood, indigenous to the Caribbean. It quickly replaced boxwood as an instrument wood. Its color, a rich deep brown to black, also appealed to the tastes of the times. Native to Jamaica and Cuba, like most tree species it is known by several names – Jamaican ebony, Ebony cocuswood, Grenadilla and West Indian ebony. It is also called the Jamaica Rain Tree because it comes into bloom with brilliant yellow-orange flowers almost immediately after a rain event.

Like African blackwood it grows in tropical scrublands, a habitat to which it has become able to survive and become drought resistant by adding only incremental growth in its yearly cycle. This growth pattern gives cocuswood the same properties that have come to be prized in African blackwood – extreme density, machinability, and stability. Also like blackwood, cocuswood belongs to the pea family Fabaceae. It is a legume, enriching the soil in the often marginal habitats it is known to occupy. During a relatively brief period cocuswood was the wood of choice for European woodwind makers but unfortunately, since its habitat was limited to Cuba and Jamaica and the tree was even smaller than blackwood (average diameter of 3-6 in/8-15 cm, as compared to mpingo harvestable size of 9.5 in/24 cm), stands of the tree were soon decimated and no conservation initiatives were instituted to protect it for the future. Today, it is only available in small quantities at very expensive prices. Possibly because its numbers were depleted so many decades ago and it is of little consideration in trade it is not listed by CITES or on the IUCN Red List.

As a result of the scarcity of cocuswood, African blackwood, which is called grenadilla in the instrument trade, began to be used in the manufacture of fine quality woodwind instruments, and today is generally regarded as almost irreplaceable. Since blackwood is a tree that grows twisted and full of flaws, extracting high quality timber is extremely difficult. Graders at the mill can relegate up to 90% of the wood to the scrap pile. Additionally, instrument makers are finding that they lose up to 20% of their workpieces during the machining process at the factory. It is thought that this may be due to the increased exposure of mpingo to human-set fires in the woodlands where it grows which are in excess of what would occur naturally. This may create hairline cracks and invisible defects in the wood that cause it to explode apart on the lathe during manufacture. Such large amounts of loss put an added demand on remaining stands of timber.

The Great Highland Bagpipe

Evidence for the evolution of instrument woods can be found in the history of the Scottish bagpipe trade. Although bagpipes are associated with the music of the Scottish highlands, indication of similar instruments dating to 1,000 years ago has been found in various parts of Europe and in northern Africa and western Asia. The instrument may have been inspired by flotation devices made of animal skins used to cross bodies of water, because early bagpipes were made of the skins of goats, sheep or cows. Before the introduction of imported woods, the pipes were traditionally made from European fruitwoods or the dense wood of the golden chain tree (Laburnum anagyroides), but when exotic timbers became available during the 1800’s, cocuswood and Gabon ebony (Diospyros ebenum) quickly replaced these local woods.

David Glen (1850-1916) was one of the most influential bagpipe makers in the history of the art. He came from a family of pipe-makers. His father’s brother, Thomas MacBean Glen, established a business called J&R Glen in 1833 and his father, Alexander, started making pipes around the same time, teaching his son the skills needed to learn the trade. In 1869 his father died and David, then 19, took over the business. In 1876 he married and had five sons, who also grew up learning to build bagpipes. In 1912 the family business was renamed David Glen & Sons; it would go on the produce thousands of bagpipes and survived until 1976. Within Scotland, Glen was even more widely known as a musicologist, because between 1876 and 1900 he collected nearly 1,100 pieces of music for the bagpipe which were catalogued and published in 17 parts. The music books were sized to fit in the bottom of a bagpipe case and many long unused bagpipes that are found in hereditary estates will often have a couple of David Glen music books tucked away in storage beneath the bagpipes.

Edinburgh bagpipe maker David Glen in his workshop around 1910, showing shelves of bagpipe blanks behind him which are virtually unchanged from those still used today. There are likely to be several woods represented among the blanks, since surviving Glen bagpipes are made of one of the three dominant species then in use – cocuswood, Gabon ebony or blackwood.

Over the course of the 20th century supply problems for cocuswood were becoming evident and Gabon ebony was also falling out of favor because of its brittle nature, tendency to dull tools due to its high silica content and the toxicity of its dust. Evidence of the transition from cocuswood and ebony to African blackwood can be traced in the trade catalogs of two prominent bagpipe suppliers active during this period – Peter Henderson Ltd. and R.G. Lawrie. Henderson’s first documented set of bagpipes made of African blackwood was in 1882, and listed as sold to ‘Pipe Major Willie Gray’. In 1900 blackwood appeared on the Henderson price list, along with cocuswood and ebony. Pipes made of blackwood apparently were considered an upgrade, because there was a 10 shilling extra charge for them. Whether this is because the wood was considered more desirable or was simply more expensive to obtain is unclear. An R.G. Lawrie catalog from the 1920’s or 1930’s stated that Lawrie sold a range of 15 different bagpipes made from ebony or cocuswood, but added the footnote: “Extra for African Blackwood.” Other footnotes in the catalog stated, “African Blackwood, Gaboon Ebony and Cocus, the timbers from which our Bagpipes are made, are selected with the utmost care” and “African Blackwood is recommended for abroad as it is best suited to stand climatic changes.”

Although some bagpipe makers of the time shunned African blackwood and continued producing cocuswood and ebony pipes until the 1950s, for the most part the 1920s marked the transition to African blackwood, and it remains, by far, the dominant wood of choice today. Since the 2017 CITES restrictions, however, manufacturers have been experimenting with synthetic or laminate materials and a wider range of species such as Swartzia cubensis, known as Royal Mexican ebony or katalox, which is currently unrestricted, Combretum imberbe – leadwood, Colophospermum mopane – mopane and Guaiacum officinale – Lignum vitae.

Creation of the Modern Woodwind

Much of the technology and artistry of modern woodwinds was developed in Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Paris was an important center for development of the arts during this period and its National Conservatory of Music and Dance, founded in 1795, trained many aspiring performers in the crafts of their chosen expression. Teachers and musicians had the opportunity to collaborate and exchange ideas and were the force behind the innovations that produced the instruments of modern times. Many musicians of the era were also inventors who envisioned modifications that would produce a better instrument more capable of creating the harmonies and intonations they wished to convey. Therefore artistry and manufacturing progressed in tandem. The musicians who founded instrument companies often came from a family that had practiced music for several generations, and some of the companies that were so important in the development of the orchestral instruments for classical music have been passed down through succeeding generations. An overview of the history of several of these important innovators is recounted below.

Buffet Crampon

Buffet Crampon is a French woodwind instrument company which produces professional quality instruments for the world’s most renowned musicians and orchestras, as well as student models for beginners. With subsidiaries in the US, Japan, China and Germany, it has become one of the world’s leading manufacturers of clarinets, oboes, saxophones, English horns and bassoons. It was founded in the early 1800s.

History – Denis Buffet-Augur (1783-1841), the founder of Buffet Crampon, was born in the La Couture region of France into a family of woodturning experts. La Couture was well known for the expertise of its artisans, skilled in the making of woodwind instruments. Wishing to expand his business to a larger market, Buffet-Augur moved to Paris and in 1825 set up an instrument shop in the heart of the city, producing clarinets that quickly became recognized for their outstanding quality.

In 1830 Denis’ brother, Louis-August (1789-1864), also a maker of woodwinds, followed him to Paris and started his own workshop. Of importance in the historical development of woodwinds is the collaboration that developed between Louis-August and the highly gifted clarinetist and Paris Conservatory instructor, Hyacinthe Klosé (1808-1880). The fruitful interchange between these two imaginative and inventive minds produced a system that forever changed the way certain woodwinds were manufactured and played. Working together over a number of years, they created a pioneering keywork system adapted for the clarinet, based on the Boehm system and using seventeen keys, which produced a far superior sound and enabled musicians to attain greater proficiency in their use of the instrument. This became known as the “Boehm-Klose system” and has since become the standard for clarinets in France, England and the Americas. They also developed an improved Boehm system flute and devised a similar application for the oboe.

The son of Louis-Auguste – also named Louise-August (1816-1884) – was an inventor like his father. Beginning in 1845 he worked in his father’s shop and was awarded several patents for woodwind innovations between 1859 and 1862. When his father died in 1864 he took over operation of the business.

Denis Buffet’s company became so successful that in 1850 it opened a workshop 30 miles northwest of Paris at Mantes-la-Ville. This area was located near the river Seine and important railway lines that simplified the acquisition and distribution of raw materials and finished products. It had become an important center for instrument manufacture since Louis XIV had first established wind and brass manufacturing there in the early 18th century. The Buffet workshop would become their primary factory and over time other French woodwind manufacturers would set up production facilities in the same area. In 1841, after the death of Denis Buffet, his son Jean-Louis (1813-1865) took over the company, renaming it Buffet Crampon by adding his wife’s name. Through several subsequent changes of ownership this is the name it carries today, still holding to the standards of excellence of manufacture first established by its founders.

Green Line Instruments

Buffet Crampon has also led the industry with its introduction of an eco-friendly line of instruments labeled “Green Line,” made from a patented product that primarily contains finely ground blackwood. This proprietary process utilizes wood shavings and waste from the production process to manufacture a material that can be molded into music blanks and worked the same as a timber species.

A positive result of this technology is that it produces an instrument that is in some ways superior to those milled from trees. A woodwind made with Green Line material does not warp or expand and contract with climactic changes, remaining stable in all playing environments, a property important to musicians who travel the world. Significantly, it also eliminates the risk of cracks – a traditional problem with woodwinds. This innovation is a major development towards easing the international demand for grenadilla.

Henri Selmer Paris

The story of the Henri Selmer Paris Company can be traced back to 1770 through seven generations to a peasant family from Loraine, headed by Johan Jacobus Zelmer, a restless man who ardently wished to escape peasant life and move to the city. In order to do so he joined the army and played in the regimental band. His children and grandchildren followed in his footsteps, developing a family tradition steeped in music. His grandson, Charles-Frédéric Selmer, became a student of Hyacinthe Klosé and was so talented that when he graduated a special “Prize of Honor” was created for him. Frédéric passed on his passion for music to his sons Henri and Alexandre and impressed upon them his great frustration at the intonation problems that were common in the imperfect instruments then available and his dream that they would someday be improved.

Like their father Charles, Henri and Alexandre Selmer both trained at the Paris Conservatory, becoming skilled in the art of the clarinet. Having become proficient in making his own reeds and mouthpieces, in 1885 Henri established a business to produce those parts for other musicians and this became the first Selmer company. He also began to repair clarinets, and eventually produced models of his own design, leading to the opening of his first instrument factory in 1900. The instruments manufactured were of such high quality that they received immediate recognition.

Henri’s brother Alexandre on the other hand, had chosen to leave France and immigrate to the United States, where he secured a succession of positions as principal clarinetist with the Cincinnati Symphony, the Boston Symphony and the New York Philharmonic. While employed with the Philharmonic he visited France and on the return trip brought back with him several of his brother’s clarinets to use in the orchestra. When they were heard and tested by other musicians, they created such a sensation that the Selmer store in Paris was soon receiving numerous orders. To satisfy the US demand for Selmer-made products, in 1900 Alexandre opened a retail shop in New York City. This began an association between the French and US companies that has continued until the present. By 1927, when Alexandre repatriated to France, the US business, which was itself manufacturing Selmer instruments as well as selling those from Paris, became an independent entity and is still functioning today.

From 1910-1920 Henri opened new facilities in Paris to diversify and industrialize production of the whole woodwind family of clarinets, oboes and bassoons, and in 1919 established a separate factory at Mantes-la-Ville for saxophones. Between 1928 and the early 1980’s Selmer also had a branch in Great Britain. When Henri Selmer died in 1941, his son Maurice took over, and this tradition continued with each succeeding generation. Over the years numerous developments in design, production techniques, and machine tools produced instruments with wider harmonic range and improved ease of performance, and this insistence on innovation and excellence has remained a mark of the company throughout its history. Today, after over 125 years, Selmer-Paris is still independent and the exclusive property of its founding family, with the fourth generation of the Selmer family managing its operations. Its current president, Jérôme Selmer, is the great-grandson of Henri and the company is still committed to achieving the highest standards and ever exploring new possibilities for excellence and innovation – these are the goals that had once been only a dream for Henri and Alexandre’s father, Frederic Selmer.

F. Lorée - Paris

The F. Lorée company was founded by François Lorée in 1881, but it was heir to a tradition that had begun two generations earlier with the Triébert instrument firm. Lorée himself had trained and become foreman in the workshops of Triébert, which had been founded by Guillaume Triébert and passed on to his sons, Charles-Louis and Frédéric, both of whom were teachers of the oboe at the Paris Conservatory and became important in the history of the instrument. In 1855 the Triébert company had produced a version of the Boehm system oboe and made improvements to the French bassoon, a double reed instrument in the oboe family. Besides instruments, the Triébert showrooms offered perhaps the most extensive stock of oboe music available during the 19th century, including many works available nowhere else. Charles-Louis and Frédéric both wrote professional and student compositions for the oboe and played significant roles in redesigning the oboe for student use. The work of the Triébert firm may be said to have established the definitive characteristics of the French-style oboe.

After Frédéric Triébert died in 1879, François Lorée decided to form his own business and established the F. Lorée company in 1881. Nevertheless he carried on the Triébert tradition, primarily producing oboes and English horns and acquiring the contract to supply oboes to the Paris Conservatory. At his death in 1902, his son Lucien took over the firm. Of importance to the evolution of the modern oboe is the collaboration between Lucien Lorée and Georges Gillet, who is known as one of history’s most phenomenal oboists. Gillet became widely respected, not only for his personal performance style, but also for his imaginative brilliance in advancing the development of playing technique and technical refinement of the instrument itself. In his work as teacher at the Paris Conservatory from 1882-1919, he inspired a generation of students with his zeal and dedication.

Working together, Gillet and Lucien Lorée modernized the oboe and invented the “Conservatory Plateau System” which was widely adopted by soloists around the world. Oboes under this system had covered tone-holes rather than open rings, making it easier for the musician to completely cover the holes. In 1925 the firm was acquired by Raymond Dubois, and ten years later his son-in-law, Robert de Gourdon joined the firm. Robert took over management in 1957 when Dubois died, and in 1967 his children Anne and Alain joined the company. At present Alain is the director of the company, and the third generation of de Gourdons, Olivier, Virginie and Marie-Léa de Gourdon, are also involved in the company’s operations.

F. Lorée is the oldest firm in the world to specialize in the manufacture of oboes and for close to 150 years, it has continued in the traditions of its founders, improving the playing capability of its instruments and using the most modern precision machinery to produce instruments that deliver concert quality performances. In addition to manufacturing a complete line of oboes for professional musicians, it also specializes in a student line under the trade mark name of Cabart which are lighter and have a simplified system for those with shorter reach. The grenadilla (Dalbergia melanoxylon) wood it uses is FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certified and accessed from Mozambique.

Marigaux

The Marigaux instrument company was founded in 1935, through a collaboration between three friends, each of whom was well equipped to handle one aspect of the business. Jules Marigaux was the artist, an oboe player of international renown. His father had been foreman at the Buffet Crampon factory and he himself had also trained at Buffet Crampon and consequently was well versed in the expertise needed to manufacture wind instruments. Charles Strasser was a businessman from Switzerland. Having mastered several languages he was able to handle what would quickly become an international business. Lemaire took over the management of instrument production and oversaw the establishment of a factory at the site it occupies today on the Boulevard de la Villette in Paris. Saxophones and flutes were produced at the Paris location and a second manufacturing center was also established northwest of Paris at La Couture-Boussey in the village of l’Eure to produce oboes and clarinets.

Like the historic manufacturing area of Mantes-La-Ville closer to Paris, La Couture-Boussey where the Marigaux factory is located in French Normandy has been known as a center of French artisans since the 17th century. At that time boxwood was the most highly valued species for instrument use and the richly forested lands in this part of France had an abundance of boxwood trees. Local artisans, taking advantage of the resource, set up workshops to use their expertise in woodworking and produced woodwind instruments of high quality. The area soon attracted instrument makers from other regions and over time dynasties of family businesses were established, expert at the art of instrument making. The most famous was Jacques-Martin Hotteterre (1674-1763), a French composer and flautist who became a musician to King Louis XIV, as well as a teacher to other aristocratic patrons. He was the first musician to play a transverse flute in the orchestra of the Paris Grand Opera and wrote and published the first European flute manuals, which were widely distributed. In 1888 the artisans of La Couture-Boussey created a Museum of Wind Instruments. This was the first instrument museum in France and is still open today. A virtual tour of the central display area of instruments and machinery can be seen here.

Marigaux has also been known by the name SML, from the combination of the three founder’s initials. The company was quickly recognized for the high quality of its oboes and after the Second World War when jazz became popular it produced several lines of saxophones that became popular in both Europe and the US. After 1982, however, it discontinued making saxophones and now devotes its facilities to manufacturing a full line of oboes and oboe-related instruments, including musettes (bagpipe family), oboe d’amore, English horn and bass oboe. It manufactures a student line for young children and beginners, an advanced line for more experienced musicians and a professional quality range for concert musicians, combining the talents of musicians and technical teams to produce increasingly refined instruments.

Chambre Syndicale of the Instrumental Invoice

The Chambre Syndicale of the Instrumental Invoice (CSFI) was founded in 1890 to form a cooperative and advocacy association for French companies and craftspeople that manufacture, distribute and export musical instruments and their accessories. Its activities cover a wide range, from oversight committees campaigning for reasonable trade regulations, to educational initiatives designed to popularize the cultural expression of music throughout the nation, to publication of economic studies of international trade and other articles related to instrument manufacture.

One of its initiatives, launched in 1999, was the result of a study reporting that less than 3% of children practiced a musical instrument in France. To more widely expose children to music, CSFI launched its “Orchestra at School” program to urge educational institutions to include music classes in the curriculum and to consider including school orchestras as part of their cultural activities. By 2007 150 classes had been organized and by 2014 1,000 school orchestras were operational. Today “Orchestra at School” is an independent entity operating on its own to influence an increased percentage of the 55,000 schools in France to give music a viable place in their academic studies. An associated initiative is its “How Does it Work” seminars for young students to introduce them to a range of musical instruments, from pianos to wind, string and percussion instruments.

CSFI also plays an educational and advocacy role for the music industry, publishing explanatory articles to clarify the often-changing regulations about the trade and use of raw materials used by instrument manufacturers, such as metals and timbers. Together with the Confederation of European Music Industries (CAFIM), a similar European-wide music advocacy group, it works actively to promote and safeguard the interests of the European musical industry.

CSFI has taken an active role in dispersing information to its membership about the African Blackwood Conservation Project, and a number of its member organizations are generously supporting the replanting efforts of the ABCP.

Brenda Schuman-Post

Brenda Schuman-Post is a freelance oboist who is passionately concerned about the future viability of the mpingo tree and the present threats to its long term sustainability. Since 2003 she has taken on an advocacy and educational role in teaching other musicians about the importance of the wood used in their instruments and its conservation status in its home range in eastern Africa. To this end she has created a multi-media lecture-performance entitled “Sustainable African Blackwood: Harvesting the Music Tree,“ which she presents to diverse audiences including musicians, museum goers, university faculty and students, botanists, conservationists, environmentalists and students of African studies. During the lecture she uses over 100 slides and videos that show the tree’s habitat, methods of cutting and harvesting, wastage incurred in the milling process, and various forces that are impinging on the future viability of the species. She also discusses the trees’ conservation status and the efforts that are currently ongoing to save the species.

In 2008 she was awarded a Global Connections grant called “Meet the Composer.” The purpose of the grant was to assist “the creative and professional development of living composers through the performance of their work worldwide.” With funding from the grant Brenda traveled to Tanzania and collaborated with Sebastian Chuwa, founder of the ABCP and his associate, environmental musician Sixtus Koromba, who helped in bringing together a group of musicians to improvise original scores drawing upon both Western and African styles. She also performed at Moshi Environmental Day ceremonies and other local venues and traveled to sawmills and harvesting sites in southern Tanzania to see how the trees are located, harvested and milled.

In Brenda’s words, “We will build bridges between our diverse and co-dependent cultures. For possibly the first time in history, the Western musical community, still profoundly unaware of the threat to the primary tree that becomes woodwind instruments, and the African communities that play so unappreciated and yet so significant a role in Western music, will be bonded through the music that both are responsible for creating. This project is about interconnectedness.”

Brenda is known for her creative improvisational style and for demonstrating the capabilities of the oboe as a solo instrument, offering workshops in Extended Techniques and Free Improvisation. In 2003, she won a Star Trek Idol Talent Search by composing and performing her “Fantasy on Themes from Star Trek” for solo oboe. Brenda is a Buffet Crampon USA Performing Artist and plays exclusively on the Buffet Crampon 3613 Greenline oboe.