Conservation status

Lone Mpingo with Dust Devil on the African Savanna

Conservation Status Of Dalbergia Melanoxylon In The 21st Century – A Review Of The Literature

The amount of Dalbergia melanoxylon used by the instrument trade, African carvers and woodworkers is difficult to estimate. Statistics show that numbers harvested for the manufacture of woodwinds through the years have remained fairly constant, but its use by African carvers has expanded with the growing tourist industry in eastern Africa. In Kenya alone there are 60,000 carvers but with the lessening availability of African blackwood they are now using over 50 other woods in addition to blackwood. Additionally the carvers are the most efficient users of the wood because the curves and fluidity of their unique stylistic designs take advantage of parts of the tree that would be discarded by its other users.

Despite Tanzania and Mozambique both having restrictions and registration requirements for tree extraction, supervision of their vast woodlands and adequate law enforcement remains an impossible task given the lack of government revenue. An in-depth national inventory of the tree has been out of reach for the same reasons. Therefore, estimates of mpingo populations, extraction rates and remaining habitat are, for the most part, guesswork. The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) determination of its status as ‘Near Threatened’ in 1998 was not based on specific data collected in the field, but on studies that themselves relied on an assortment of written commentaries. Most people who have studied the extraction problems of Dalbergia melanoxylon consider the IUCN classification as highly conservative and the IUCN itself refers to the categorization as ‘needs updating’.

Beginning at the turn of the 21st century, a new history began to be written about mpingo conservation, as a small paradigm within the larger picture of worldwide nature conservation. Significant developments during the past 20 years have had major implications for the future of African blackwood due to one primary international factor – the emergence and vast expansion of the economic powerhouse of China, and to a lesser extent, of India and southeast Asia. Because of an emerging middle class in these nations, the world is witnessing a repeat of the international trade environment that developed during the Industrial Revolution in Europe, which precipitated a vast expansion of extractive industries to fuel industrial and consumer demand. As in China and Asia today, millions of people were then rising out of poverty and were intent on attaining the luxury items that have long been the mark of upward mobility and affluence in all societies. A major difference between today’s world and that of 19th century Europe, however, is that the emerging class in Europe in 1850 (if calculated at 20% of the population) amounted to around 40 million people, while an extrapolation using that same percentage today would estimate that over a half billion people are moving out of poverty.

The pressure caused by the rise in ‘conspicuous consumption’ of this number of people, combined with the ongoing demands of the already industrialized nations of the West, are crucial factors generating the present disturbing environmental crisis that is decimating species’ populations throughout the world. Illegal trade in threatened and endangered plant and animal species is skyrocketing and extinction rates of marginal species are alarming. As scarcity increases, prices concomitantly soar, fueling the demand and increasing criminal activity surrounding these sectors. Scientists suggest that the planet is now losing species at 1,000 to 10,000 times the normal ‘background’ rate and is in the midst of its sixth mass extinction of plants and animals during the past 500,000,000 years. The difference during the present crisis is that, whereas past extinctions were brought on by natural factors, an estimated 99% of the responsibility for the present crisis is due to human activity. In addition, the spiraling human population not only increases consumer demand but causes massive habitat loss when land is cleared for human occupancy. In a complex ecological web, because every species’ extinction potentially leads to the decline of others bound to that species, numbers of extinctions are likely to snowball in the coming decades if ecosystems continue to unravel.

CITES – The Convention On International Trade In Endangered Species Of Wild Fauna And Flora

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an international agreement between 182 participating countries (plus the EU) to enforce trade regulations to protect a designated list of threatened and endangered species. The CITES Appendices offer differing levels of protection for over 35,000 species and are legally binding on the participating countries. Its governing body, CoP, or Conference of the Parties, meets every two or three years to review selected species that are considered under risk and deliberate as to whether they merit inclusion in one of the CITES Appendices. These meetings have not only served as a means to protect the natural world but, importantly, have also generated a vast amount of documentation by some of the world’s most astute thinkers and scientists. In preparation for CoP meetings, in-depth scholarly reports are submitted by member states in order for the CITES Secretariat to come to an informed decision for any particular species under review. These reviews have generated a wealth of information about the world’s most vulnerable plants and animals. Dalbergia melanoxylon has been seriously considered for a CITES listing twice, once in 1994 and again in 2016. Both proposals initiated research studies that have become an important source of information for a tree that has otherwise been so little researched.

CoP9 – 1994

In 1994 an attempt to regulate the trade in African blackwood was put forward by Kenya and Germany with a proposal that its inclusion on the CITES Appendices should be reviewed at the next meeting. (See proposal here.) That proposal was never ruled upon by CITES, however, because of insufficient data and because agreement could not be reached between the countries which would be directly impacted by a CITES listing. Therefore the 1994 proposal was withdrawn, and the species remained unregulated internationally.

Because of the increased international concern that was raised about the species at that time, Fauna and Flora International (FFI) sponsored several studies. One of the most informative is a Master’s dissertation written in 1995 by Hazel Sharman. It is called “Investigation into the Sustainable Management of a Tropical Timber Tree Species, using Dalbergia Melanoxylon as a Case Study.”

Describing its then current conservation status, she wrote, “Whilst it may not be biologically or ecologically threatened, it may well be commercially threatened. The constant removal of individuals with the same characteristics will be extremely harmful to the population structure, possibly resulting in genetic erosion. The end result may be a constant decline in the population until it is commercially extinct, leaving, if any, a population structure which may not be able to reproduce and that if it can, will reproduce individuals without those characteristics so highly prized by the trade and human society and a population weak and vulnerable to natural disaster and environmental change. There is a definite need for the implementation of an effective and applicable management strategy. What must be recognised is that utilisation of Dalbergia melanoxylon is not going to stop whether legally or illegally, but this utilisation should at the very least be managed and monitored. What must be addressed is how scientific knowledge can be mobilised most effectively to ensure the persistence and protection of the trade, and the species itself.” In 1999 the ABCP published an overview of the existing literature about African blackwood that was available at that time. See article: “A Review of the Literature – 1999.”

As an outgrowth of this international concern about mpingo, two conservation initiatives were created in Tanzania. The Mpingo Conservation and Development Initiative (MCDI – formerly the Cambridge Mpingo Project), established in 1994, which operates near Lindi in southern Tanzania, is a cooperative venture between over thirty local communities which have received FSC certification for their timber resources. These communities maintain a regulated system of sustainable harvesting for several important tree species growing in the area, including mpingo, and have established their own trade networks for marketing of the timber, thus realizing greater return for their natural resources. The African Blackwood Conservation Project (ABCP) in the Kilimanjaro Region of northern Tanzania instituted a replanting and educational outreach project in 1996 to raise public awareness and to reestablish the species in areas where it had formerly grown. It replants blackwood in sites where the trees will be relatively protected, like on private farms, and school, public and community landholdings.

China And The Illegal Trade In Timber Species

It is unfortunate that international agreement to regulate the trade in African blackwood was unable to be reached at the 1994 CITES meeting, because during the next two decades international events would jeopardize even further the future, not only of African blackwood, but of numerous precious timber and at-risk animal species around the world. With the emergence of India, southeast Asia, and most significantly – China – as economic powerhouses competing with Europe and the US for the commodity markets of the world, their activities in producing products to satisfy the needs of their emerging middle class have resulted in widespread exploitation of animals and timbers, many of which are already threatened or endangered. Some of these operatives are not government sponsored but cartels operating illegally, in violation of national and international laws, to take advantage of the opportunistic trade environment that has been established in these emerging economies. Because the demand for luxury consumer products is so great and the trade so lucrative, law enforcement has been lax at best. As it has become obvious that numerous timber and animal species across the world are being harvested close to extinction, conservationists have begun to raise the alarm.

Although the illegal trade in timber species has not been as widely reported in public media as animal exploitation, profits from that trade far exceed those from wildlife. It is a major criminal activity, amounting to an estimated USD 50-150 billion yearly (Interpol). It has been estimated that globally, 15 to 30 percent of timber extraction is done illegally. Compare this figure to approximations for wildlife crime, estimated at USD 7-23 billion annually, and the magnitude of the problem becomes obvious.

China and India are the world’s most populous emerging economies, but commercial interests within China have become of primary concern for the conservation community because of its economic goals and internal politics since the turn of the millennium. In 1999 China launched its Go Out Policy, or Going Global Strategy as an effort to promote Chinese investment abroad. During the previous decades it had amassed huge amounts of foreign reserves, thus putting upward pressure on the foreign exchange rate of its currency. To remedy this it began an aggressive campaign to assist domestic companies in developing global strategies to exploit opportunities in expanding markets. China’s huge production capacity and low labor costs have facilitated this strategy and been at the base of its precipitous rise as one of the world’s largest economic powers, second only to the United States.

Another factor, one that has direct relevance to the world’s international timber resources, is an outcome of events on the Chinese mainland. In 1998 the flooding of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers in Central China caused massive losses in lives and homes, along with widespread environmental damage. Because the floods were assessed to have been caused by excessive logging in the upstream watershed, in 2000 China enacted a national program, called the Natural Forest Protection Program (NFPP) to mediate deforestation and restore watersheds. The program included a complete logging ban in some areas and reduced logging in others, covering over 50% of the nation’s natural forests. In 2015, China’s cabinet issued additional guidelines that called for further action – a 20% reduction in commercial harvesting of planted forests and a total logging ban on state-owned natural forest by 2020.

Because of these bans on cutting its own forests, China is now the world’s largest importer of hardwoods and tropical timber, and the recent extension of its national logging ban may assure that it remains so for years to come. China has become so successful in procuring timber resources that, whereas twenty years ago it was importing finished products such as furniture, now it has itself become one of the world’s largest exporters of furniture and numerous wood products. Today more than half of the timber being shipped worldwide is destined for China. Forest Trends, a US based think tank, has described China as the “wood workshop for the world.”

Hongmu – Chinese Classical Furniture

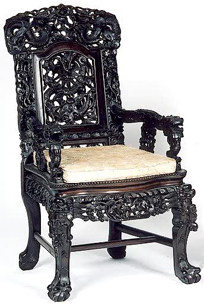

Examples of Hongmu furniture, using a variety of precious hardwoods, with mother of pearl and elephant ivory inlay.

Germane to China’s exploitation of Dalbergia melanoxylon and other precious hardwoods is its extensive use of those species in the rebirth of an historic furniture tradition based in Chinese history. Called hongmu, a word meaning rosewood, it encompasses the production of a range of cultural artworks based on the aesthetics of furniture styles developed during the Ming (1368-1664) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. Designs and wood requirements inherited from these earlier dynasties are duplicated in current times. The highly refined and richly decorated items produced have become cultural icons and are widely sought by wealthy connoisseurs and the rising middle classes. They have become a symbol of cultural identity and economic status throughout China.

The selection of materials for the manufacture of hongmu artwork relies on a specific listing of 33 woods (of which 16 are endangered or near-endangered) which are considerable highly desirable in order to duplicate the appearance of pieces crafted during the earlier periods. They are largely Dalbergia and Pterocarpus timbers which are native to the tropical regions of Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America. The widespread harvesting of these species deprive local forest communities, because they are often also of crucial importance to indigenous native populations for medicinal and domestic uses and livelihood activities like marketable handicrafts and artwork.

This excerpt from a 2014 report in Forest Trends comments on the escalating use of Hongmu species in the Chinese timber trade: “The total volume of log imports (both hardwood and softwood) has increased from just over 13 million m3 in 2000 to nearly 52 million m3 in 2014, with a cumulative volume of nearly 474 m3 and cumulative value of $75.2 billion over these 15 years. In 2014, of the 15 million m3 of hardwoods imported by China, nearly 2 million m3 were classified as hongmu, and this proportion has risen significantly since 2009. In terms of value, more than one third (35.1 percent) of China’s hardwood imports in 2014 were rosewood, compared to 29 percent in 2013 and a massive jump from 3 percent in 2000. This contributed in part to a 50 percent jump in value of China’s overall log imports for 2014, compared to a 23 percent increase by volume (the larger increase by value indicating an increase in high-value species).” (Source: “China’s Hongmu Consumption Boom: Analysis of the Chinese Rosewood Trade and Links to Illegal Activity in Tropical Forested Countries,” p. 4.).

Fortunately for African blackwood, but unfortunately for other species, the most highly sought Hongmu species are those with a rosy color and not pure black like mpingo. Nevertheless Dalbergia melanoxylon is on the list, making it a prime target species. One of the most highly sought species, because of its exquisite pink hue, has been Siamese rosewood (Dalbergia cochinchinensis), indigenous to Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia. Despite a CITES listing for the species in 2013, because it is so highly prized by art connoisseurs in China, exploitation of the species has continued and its ever-increasing rarity has resulted in dramatic price rises, thereby offering huge financial incentives to trade in the wood, albeit illegally. Such practices have undermined the rule of law in many markets. Thailand forest reserves, where some of the last remaining large trees survive, are guarded by forest rangers with rifles. Despite this, there are accounts of groups of dozens of poachers, armed with chain saws and AK47s, surreptitiously camping out in forest reserves to track down and harvest some of the last remaining stands of this highly prized tree.

A quote from an Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) document reporting the illegal trade in this species describes the dynamics of the situation, one that can be extrapolated, although to a lesser extent, to that of mpingo in Africa: “While responsibility lies with countries in which the tree grows (Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia), it is the state-supported commodification and commercialization of China’s rich Hongmu cultural heritage that has provided all the money, and China is where all the timber has gone.“ (Source: “Routes of Extinction: The Corruption and Violence Destroying Siamese Rosewood in the Mekong,” p. 1.)

CoP17 – 2017 CITES Regulations Affecting Dalbergia Melanoxylon

Although no international agreements to regulate the trade in African blackwood had been reached at the CoP9 meeting in 1994, by 2016 it had become clear that numerous timber species across the world were beginning to be harvested close to extinction. The world conservation community was taking note, and in an historic move that made conservation history, on January 2, 2017 the 17th meeting (CoP17) of CITES passed the most far-ranging measures ever adopted by the organization. It is referred to as “the most critical meeting in the 43-year history of CITES.” Of relevance to the future of Dalbergia melanoxylon is that CoP17 included all Dalbergia species under its regulatory mandate, amounting to over 300 tree species, many of which have become increasingly at-risk, like African blackwood. (See CoP17 proposal here.)

John E. Scanlon, Secretary-General of CITES, issued the following statement: “CITES CoP17 was a game changer for the world’s wildlife, with international trade in 500 more species brought under CITES controls, including high value marine and timber species. CITES also adopted a vast array of bold and powerful decisions addressing critical areas of work, such as curbing corruption and cyber-crime, and developing well-targeted strategies to reduce demand for illegal wildlife. These far-reaching outcomes of CoP17 will have impact on wildlife and ecosystems, as well as on people and economies. We are all now focused on the implementation of these decisions for which we need equally bold concrete actions.”

The CITES decision was supported by a number of studies. Those most germane to Dalbergia melanoxylon are listed at the end of this article, along with other non-CITES investigative studies about the timber trade in eastern Africa. Of particular note is a document submitted by Germany entitled, “Trade study of selected east African timber production species” by Anthony B. Cunningham. It contains information about timber availability, logging and illegal harvesting of three economically important species, one of which is African blackwood. Attention is given to the role of China in the often illegal harvesting and export of valuable hardwoods in Africa since the turn of the century.

Another study funded by TRAFFIC surveys the timber trade in the east African countries of Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia and Mozambique, assessing it in terms of timber flows, the legal instruments that have been designed to control the trade and ways in which they have been circumvented. (“Overview of the Timber Trade in East and Southern Africa: National Perspectives and Regional Trade Linkages,” by Kahana Lukumbuzya and Cassian Sianga, 2017.)

Below is an overview of the trade situation for Dalbergia melanoxylon in Tanzania and Mozambique, based on information supplied by studies listed in the bibliography.

Timber Harvesting In Tanzania And Mozambique

A trade package is a particular combination of species from a geographic area that are accessed and/or exported together, and often it is timber logging that first occurs because tree clearing opens a portal for the acquisition of other species that live within the area. In Egyptian times 5,000 years ago, an era in which Dalbergia melanoxylon was also considered a precious tree species used to manufacture artworks for elite consumption, the trade package of the time, as depicted in their temple murals and writings, was ebony, ivory, gold and slaves. In current times an equivalent trade package in both west and east African is the concurrent exploitation of elephant and rhino horn, pangolin scales and timber species.

Tanzania and Mozambique are particularly vulnerable because of their great timber resources and their proximity to the Indian Ocean. The Port of Zanzibar in the Indian Ocean north of Dar es Salaam also makes them particularly vulnerable to illegal trade. Although Zanzibar is part of Tanzania, it has a political status as a semi-autonomous region, able to make many of its own laws. As such, whereas Tanzania is a CITES signatory, Zanzibar has chosen not to conform to CITES restrictions. Because it is free from such oversight it has become a hub for the international smuggling of illegal shipments. Since 2009 Tanzania and Mozambique have lost over half of their elephant populations and this type of ‘weak link’ in the chain of oversight may well have been a factor because ivory has been one of the most sought-after trade items in Chinese and Asian markets.

Such misuse of these countries’ natural resources has numerous ripple effects for their populations. In both countries most of the populace rely on forest products for fuel, fuel and shelter. It has been shown that the large scale logging that has so rapidly escalated since the early 2000s has not accrued profit to the indigenous communities which occupy the land, Instead the preponderance of profit has gone to foreign companies who run the logging, or to well-connected nationals who profit at the expense of local communities. Between the loss of marketable commodities and uncollected taxes and fees, the revenue losses are enormous.

Tanzania and Mozambique each have unique internal forestry regulations and deal with international trade in different ways. Despite the fact that both countries are signatories to numerous international conventions related to biodiversity such as CITES, the Kyoto Protocol and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, only CITES has the force of law. Although illegal activities do happen in Tanzania, governance is far weaker in Mozambique, which in many ways is still recovering from the effects of its long war for independence and the following civil war which lasted until 1992. It may take many decades to rebuild strong societal, political and legal frameworks after so many years of internal conflict.

Nevertheless, the harvesting and export of mpingo from these two nations is strongly interwoven because much of the wood from Mozambique is transported north (often illegally) into Tanzania before export since Tanzania has a stronger market for timber sales. Field observations confirm that the timber transport between Tanzania and Mozambique is plagued by malpractices. There are a number of events that have led up to the present circumstances.

Although the last remaining commercial stands of African blackwood in southern Tanzania and northern Mozambique have been somewhat protected in the past by lack of easy access for harvesting and transport, that factor has changed. Since the construction of two major bridges south of Dar es Salaam, timber stocks on both sides of the international border have been severely impacted. The Mkapa Bridge across the Rufiji River 100 miles south of Dar es Salaam was completed in 2003, allowing southern Tanzania access continual access over well-constructed thoroughfares to northern ports in Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar. This resulted in an immediate escalation of logging activities in this formerly remote area. The Unity Bridge, completed in 2010 across the Ruvuma River which separates the two countries, opened an even more isolated area, northern Mozambique, to a similar access for that country. The completion of the two thoroughfares precipitated a huge increase in timber extraction throughout these two crucial mpingo habitats.

The bridge openings greatly facilitated Chinese escalation of the timber trade in eastern Africa beginning at the turn of the millennium. Alarmed at growing incidences of unsustainable logging and illegal transport, in 2004 Tanzania imposed a ban on exporting logs, a regulation that has slowed the trade and created more jobs for its own citizens who perform the value-added activities of milling the logs into usable lumber. By most accounts the ban has been reasonably well enforced. Several total bans on harvesting have also been declared, but sometimes only loosely enforced. Because of these tighter regulations, many Chinese-run logging companies moved their operations to Mozambique and as a consequence India became one of Tanzania’s primary trading partners for lumber exports.

Between 2007 and 2014 the value of Tanzania’s trade exports of forest products (both raw and processed) increased from USD 40,000,000 to USD 162,000,000. Shipping data further indicates that sawn timber exports shipped through Dar es Salaam increased from 488 tons in 2010/2011 to 35,416 tons in 2014. Kenya, India and China are Tanzania’s most important trade partners for timber, accounting for over 70% of exports. (Source: “Overview of the Timber Trade in East and Southern Africa: National Perspectives and Regional Trade Linkages.” TRAFFIC, 2017).

Both Tanzania and Mozambique have forestry services that are greatly understaffed. Mozambique’s Readiness Preparation Proposal submitted for REDD review, stated that the country only has 1,069 forest law enforcement officers, one for each 83,000 hectares of forest, whereas the recommended number for effective crime control is one officer per 5,000 hectares. Inadequate access to vehicles, supplies and equipment is problematic in both countries.

As early as 2006 a FONZA report entitled “Forest Governance in Zambezia, Mozambique: Chinese Takeaway!” by Catherine MacKenzie decried the wholescale deforestation occurring in Zambezia, one of the five northern provinces that contain most of Mozambique’s exploitable woodlands. In this document is outlined the collusion between government officials within Mozambique with foreign interests to harvest and export its hardwood species. Dalbergia melanoxylon is one such target species and Mozambique has become its primary supplier for China’s artisans.

Similarly for Tanzania, a 2007 report entitled “Forestry, Governance and National Development: Lessons Learned from a Logging Boom in Southern Tanzania,” by Simon Milledge, Ised Gelvas and Antje Ahrends, outlined a similar troubling situation in Tanzania’s primary mpingo habitat. This was sponsored by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (MNRT) of Tanzania and TRAFFIC, the Wildlife Trade Monitoring Network. It has been widely circulated and read and had the full support of the Tanzanian government, despite the fact that it highlighted collusion and illegality in the timber trade at the governmental level.

Although there are 60-70 species of Dalbergia in Africa, 43 of them are on the east African island of Madagascar and the only one considered a commercially exploitable hardwood on the mainland is Dalbergia melanoxylon. At China’s request, most of its timber imports are in log form, partially because Chinese artisans wish to mill their own lumber and partially because importers can access timbers more cheaply in log form. Even though Mozambique has a ban on the export of logs similar to Tanzania’s, it is in no way enforced as widely as in Tanzania, and exporters have found multiple ways to subvert it.

An estimated 90% of Mozambique’s timber exports are destined for China. An overview of the timber trade between the two countries was conducted by the EIA and published in 2014. It contains a careful study of import and export data comparing Mozambique’s export data with China’s figures for imports from that country. There was a large discrepancy between the two, with China reporting the higher amount, indicating that about 48% of China’s 2012 imports were not licensed or registered for export by Mozambican authorities and were therefore illegal. Commenting on these figures the EIA surmises, “The 189,615 metre discrepancy is made up almost entirely of logs smuggled out of Mozambique by Chinese companies, and is likely to consist largely of the so-called ‘first class’ species of timber – all prohibited from export. (”Note: Dalbergia melanoxylon is a ‘first class’ species.) Further estimates for timber trade between the 2007 and 2012 suggests that during that period 804,622 cubic meters of Mozambique timber, principally in the form of logs, were smuggled to China. (Source: “First Class Connections: Log Smuggling, Illegal Logging, and Corruption in Mozambique.” Forest Trends, 2014.)

Illegal Transport

In order to find better outlets for timber or avoid authorities in Mozambique some of its hardwoods are smuggled into Tanzania, There are a number of ways in which logs harvested in Mozambique are able to cross into Tanzania for shipment abroad. There are more than 40 ‘informal’ entry points through which illegal goods can slip between Mozambique and Tanzania. Because they are unofficial, immigration and revenue authorities are not present to monitor the goods that cross. There are also many informal ports along the coast where lumber can be transported to northern ports in private dhows or canoes by way of the Indian Ocean.

Dummy documentation for illegal woods and loading of illegal logs at the bottom and back of trucks to shield them from sight among other legal goods allows many illegal items to slip through undetected. Outright bribery of customs and border officials can also be a large factor in illegal transport. Timber traders who have worked long enough in a country have a unique set of contacts who are paid for their collusion in allowing certain illegal practices.

There is some evidence that the banning of log sales has actually caused rising rates of corruption because exporters find increasingly inventive ways to subvert the laws. Most Mozambique timber dealers do not have the facilities to undertake large-scale milling and manufacturing operations. The capital needed to set up such a shop is enormous and the machinery that is available within Africa, or even in China, for the most part is poorly made and expensive to fix. Many such machines have a service life of about a year. Therefore many timber exporters take the risks involved in ignoring export regulations. This is the trap that Mozambique has fallen into.

Since timber dealers are often paid a premium for non-processed logs, many have found ways to get around the log export ban by bribing officials and can actually make more money doing this than by obeying the law. For national and local governments this results in huge loses of income because much harvested timber does not get taxed and export duties are not collected, thereby depriving governmental agencies of an important revenue stream.

Such losses in turn result in reduced educational, social and infrastructure improvements, thereby affecting the lives and prosperity of their citizenry. This criminal activity is costing Mozambique tens of millions of dollars a year in lost tax revenues. The EIA study mentioned above estimated the amount of revenue lost to Mozambique through this illegal trade, calculating that in 2012 alone, the country suffered a potential tax loss of USD 29,172,350, solely attributable to its export timber trade with China. (EIA-Environmental Investigation Agency, January, 2013. “First Class Connections: Log Smuggling, Illegal Logging, and Corruption in Mozambique,” p. 6)

Another insightful look at the present difficulties for African blackwood in northern Mozambique was published in 2017 by the European Commission: “Mozambique has been described as a main exporter of D. melanoxylon (Louppe et al., 2008), supplying a growing market in China (Campbell et al., 2007). Following the depletion of stands in Senegal, Kenya, and Malawi, exploitation shifted in part to Mozambique to supply the carving industry (Louppe et al., 2008; Cunningham, 1998). Cabo Delgado province was reported to be responsible for 60 per cent of the D. melanoxylon exports from Mozambique in 2002, with an average annual export of 720 m³ (Louppe et al., 2008). In the Cabo Delgado province, overback volume was reported to be 2.2 m³ per ha (Macome, 1996, in: Malimbwe et al., 2002).

Chang and Peng (2015) noted that timber exports from Mozambique to China have risen substantially over recent years, and 10 per cent of these exports consist of D. melanoxylon. The figures given by Chang and Peng (2015) for Chinese imports of D. melanoxylon timber (round wood equivalent) were more than 5000 m³ in 2004 rising to over 33,000 m³ in 2013; based on the latter figures and taking the volume of timber harvested from an average tree as 0.1 to 0.2 m³ (Jenkins et al., 2002) the equivalent of between 170,000 and 330,000 trees would have been harvested. These figures indicate that the demand for this timber has shifted from the tone wood industry, mainly based in Europe and the USA, to the production of furniture in China. Discrepancies between licensed exports from Mozambique and data from Chinese customs indicate that nearly 50 per cent of exports to China are unlicensed and therefore illegal (EIA, 2014; Chang and Peng, 2015).” (Source: UNEP-WCMC technical report 2017. “Review of Selected Dalbergia species and Guibourtia demeusei”, p. 21.)

China And Hong Kong Ban Ivory Trade

To its great credit, the Chinese government has begun to take steps to directly confront the illegal trade in threatened and endangered species and to cooperate with the international community in raising awareness about the wildlife crisis that is decimating species worldwide. In September 2015 Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Barack Obama announced that they would work together in instituting an “almost total ban” on the import and export of ivory. To this end China has strengthened inspection and control of trade in key markets, prosecuted smuggling syndicates and worked together with international agencies to combat illegal trade in ivory, pangolin, rhinoceros horn and endangered timber. Of global significance has been its complete ban on all trade in ivory and ivory products in the country, enacted in December, 2017. Since the ban, media polls have reported a 65% decline in the price of raw ivory and an 80% decline in seizures of ivory entering the country illegally. In January, 2018, just a month after China’s ban, Hong Kong followed suit and “voted overwhelmingly” to ban its ivory trade in several phases, stopping completely in 2021. These are crucial steps towards protecting the remaining elephants because Hong Kong and the China mainland had long been the world’s largest markets for ivory.

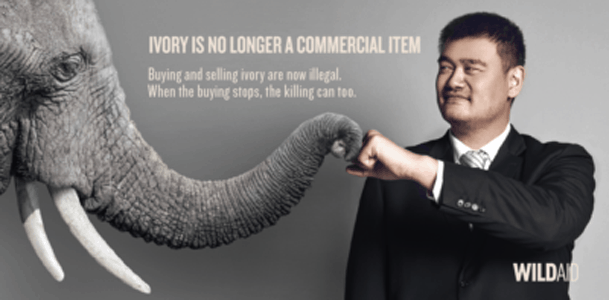

When The Buying Stops, The Killing Can Too!

Of significance in laying the groundwork for these steps have been the imaginative efforts of the US-based environmental group WildAid. While most wildlife organizations focus on protecting animal species from poaching, WildAid leads campaigns that target economic consumers, enlightening them as to the hidden costs incurred by their use of products that are leading to widespread destruction of threatened species. In China many of its citizens are not even aware that ivory comes from elephants or that their consumption of shark fin soup has led to a reduction of shark numbers by 90%, primarily because the sharks are harvested only for their fins, while the remainder of the body is thrown back into the water and left to die. To raise awareness among Chinese citizens, WildAid along with the active support of the Chinese government, is designing media campaigns with the objective of reducing demand for products by educating the public, using the WildAid slogan, “When the buying stops, the killing can too!”

Turning to positive advantage the popularity of well-known celebrity stars like Shanghai basketball superstar Yao Ming and Hong Kong martial arts master and film star, Jackie Chan, WildAid has designed imaginative media campaigns by producing brief but targeted videos that focus on an animal as it exists in the wild and showing the actual price it has to pay in order to become a consumer product. In 2006 WildAid sponsored a widely viewed ad featuring Yao Ming which graphically showed how shark fins are harvested. In a short time there was a 50-75% drop in sales of the product. In 2012 Yao Ming and WildAid produced the first documentary on ivory poaching to air nationally on China Central Television.

Ming became such a respected advocate that in 2014 he testified before the National People’s Congress, proposing that ivory sales be banned in China; that same year China carried out its first ever destruction of seized ivory. Between 2013 and 2016 WildAid and Ming collaborated with the African Wildlife Foundation and Save the Elephants to produce one of the largest public campaigns ever launched to protect elephant populations. Gathering the support of Chinese public and private media outlets, which donated over USD $180 million to the campaign, messages from numerous WildAid celebrity ambassadors were broadcast in movie theatres, on outdoor video screens, billboards and more than 25 TV networks throughout China. Polls taken since this initiative have shown a 70% increase in public awareness that ivory comes from poached elephants and a reduction in demand for ivory consumer products.

A quote from WildAid representative to China, Steve Blake, comments on the country’s efforts to abolish the trade in illegal species: “By both dismantling international criminal syndicates and increasing awareness about the poaching crisis, China is showing its commitment to protecting threatened species. We deeply appreciate our partnership with China as it means we can help deliver effective and creative messages about the illegal wildlife trade, and we will continue to support their efforts to persuade people not to import ivory.”

In addition to elephants and sharks WildAid also supports efforts targeted towards the protection of rhinos, lions, tigers, pangolins, manta rays, sea turtles and marine protected areas.

A Way Forward

At present there is little way to ascertain the current conservation status of Dalbergia melanoxylon because there is little verifiable data that has been collected which could lead to reliable statistics reporting remaining stocks of the tree and rates of extraction in relation to those stocks. Most trade statistics do not list timber extraction by species. Neither the governments of Tanzania and Mozambique, nor the international community have put forward or suggested efforts to determine exactly how close the species may be to commercial extinction in their woodlands. It is, however, quite evident from many reports, some of which have been cited above, that strong international efforts will need to be established in order to insure the future of this precious and historic resource, prized by royalty and utilized by creative artists since the beginning of recorded history. An insightful overview of where we presently stand and suggestions about a way forward are offered by Anthony Cunningham, an ethnobotanist from South Africa who wrote “Trade study of selected east African timber production species” in 2016 about the conservation status of three African hardwoods:

“While none of the three species (Afzelia quanzensis, D. melanoxylon and P. angolensis) is under the immediate threat of extinction, all of them are under severe pressure of international and domestic demand. There is strong evidence that if the current rate of harvest continues, populations of the species will severely decline and a viable timber production of these species will no longer be possible on the short to medium term. Based on field observation over many years, coupled to a thorough review of other studies, it is clear that the existing system of regulation of the harvesting of wood from miombo woodlands is not workable. A workable sustainable management system needs control at the point of harvesting. This is not possible due to the remoteness of the remaining resource-rich areas, under-resourced conservation and forestry services and the wide dispersion of cutting activities. In addition, timber supply chains are “slippery” and oiled by corruption. Elite capture of valuable timber concessions and exports by powerful, well connected individuals poses a practical challenge, including to “participatory forest management” by local communities who are expected to face overwhelming imbalances in power. Consequently, continuing to try to attain sustainable management under the current system is not a sensible option. The costs far outweigh the benefits. What is practical is support for controls higher up the supply chain (for example through Revenue authorities and customs and shipping container companies, coordinating with national forestry authorities and international conservation agencies). A coordinated approach through the International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC), formed in November 2009 by representatives from the CITES Secretariat, the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the World Bank and the World Customs Organization (WCO) could have a real impact.” (Source: “Trade Study of Selected East African Timber Production Species,” by Anthony B. Cunningham, p. 5.)

Bibliography

• CITES CoP17 Information Paper. Cunningham, Anthony B., 2016. “Trade study of selected east African timber production species.”

• CITES CoP17 Information Paper. Winfield, Karen; Scott, Michelle; Grayson, Cassandra, 2016. “Global Status of Dalbergia and Pterocarpus Rosewood Producing Species in Trade.”

• CITES CoP17 Information Paper. EIA, 2016 “The Hongmu Challenge: A Briefing for the 66th meeting of the CITES Standing Committee, January 2016.”

• CITES CoP17 Information Paper. USA-EIA, 2016. “Analysis of the Demand-Driven Trade in Hongmu Timber Species: Impacts of Unsustainability and Illegality in Source Regions.”

• Davie, Jessie, 2013. “Discussion Paper for the East African Stakeholder Forum on Assessing our Knowledge of the Illegal and Unsustainable Timber Trade in Tanzania, Mozambique and Kenya” Sponsored by TRAFFIC.

• EIA, 2013. “First Class Connections: Log Smuggling, Illegal Logging, and Corruption in Mozambique.”

• EIA, 2014. “Routes of Extinction: The Corruption and Violence Destroying Siamese Rosewood in the Mekong.”

• Ekman, Sigrid-Marianella; Wenbin, Huang; Langa Ercilio, 2013. “Chinese Trade and Investment in the Mozambican Timber Industry: A Case Study from Cabo Delgado Province.” Working paper 122, CIFOR.

• FLEGT report for European Union, 2014. “Forest Governance and Timber Flows Within, to and from Eastern and Southern African Countries – Mozambique Study.”

• FLEGT report for European Union, 2014. “Forest Governance and Timber Flows Within, to and from Eastern and Southern African Countries – Tanzania Study.”

• Lukumbuzya, Kahana; Sianga, Cassian, 2017. “Overview of the Timber Trade in East and Southern Africa: National Perspectives and Regional Trade Linkages.” TRAFFIC Joint Report.

• MacKenzie, Catherine, 2006. “Forest Governance in Zambezia, Mozambique: Chinese Takeaway!”

• Milledge, Simon; Gelvas, Ised; Ahrends, Antje, 2007. “Forestry, Governance and National Development: Lessons Learned from a Logging Boom in Southern Tanzania.” Published by TRAFFIC.

• Treanor, Naomi, 2015. “China’s Hongmu Consumption Boom: Analysis of the Chinese Rosewood Trade and Links to Illegal Activity in Tropical Forested Countries.” Forest Trends.

• UNEP-WCMC Technical report, 2017. “Review of Selected Dalbergia species and Guibourtia demeusei.”